1851 – Tulou, Air varié brillant op. 99

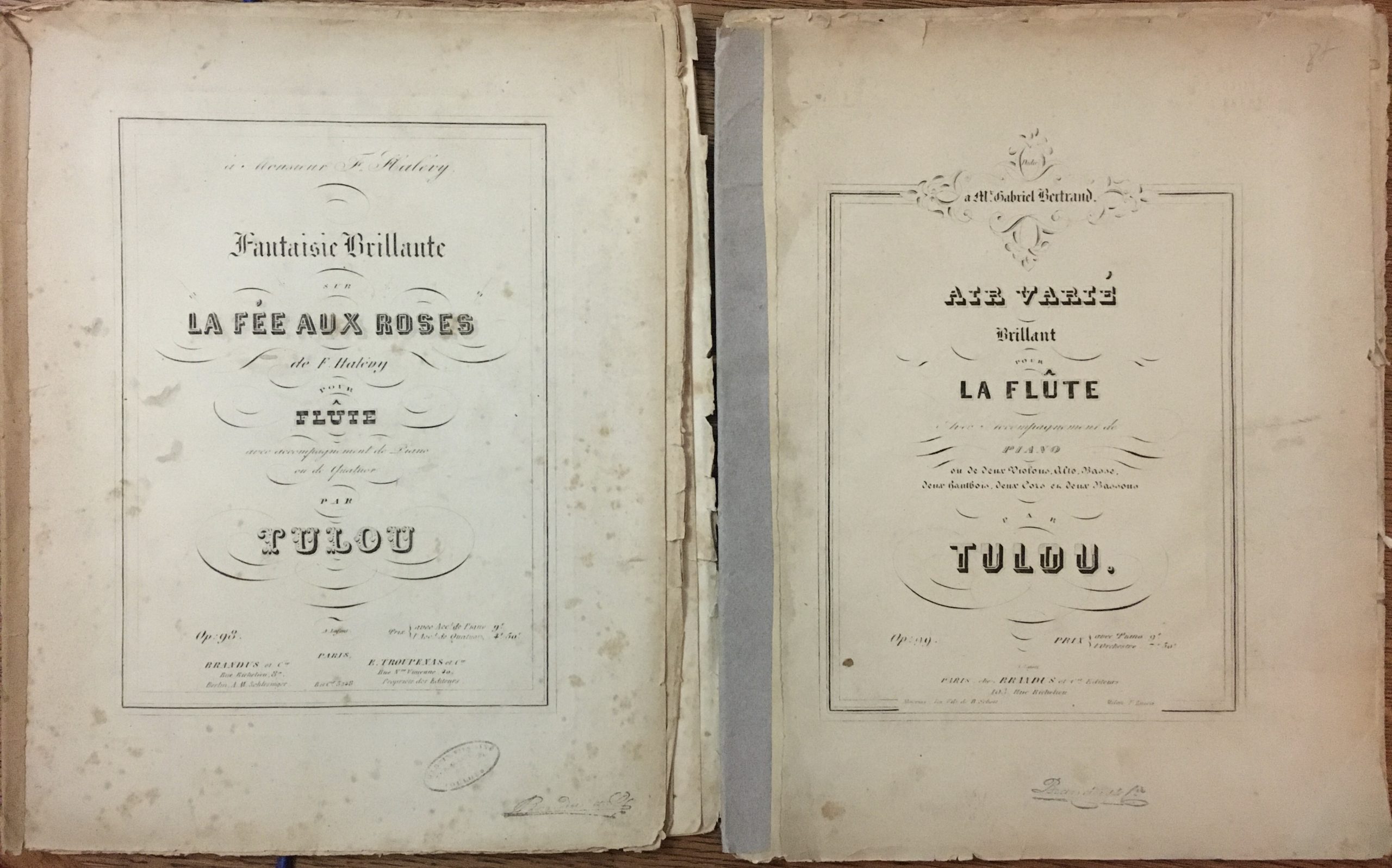

In 1851, Tulou departs from his usual tradition of composing a Grand Solo. Instead, he gives his students the Air varié brillant op. 99. The same piece is also known as op. 98. The publisher Brandus probably made a mistake in the first printing, which was passed on to other publishers (e.g. Schott) who also published the work. In 1849, Brandus had already printed an op. 98 by Tulou: Variations brillants sur La Fee aux Roses, an opera by Fromental Halevy, which was on the programme at the Opéra Comique in the same year. Brandus corrected the opus number to 99 in a second edition of the Air varié.

The Air varié is a pretty piece with a simple melody that can be varied with ease. Tulou writes three variations with an Andante sostenuto in the middle and a virtuoso ending. As in many of his concours works, he gives his students some challenging passages. The third variation in particular, with its high trills, is quite something.

In 1851, five candidates take part in the concours, three of them win a prize.

Vincent-Benoit Doudiès was born in Toulon on 30 May 1830. In 1848 he appears in Tulou’s reports for the first time who describes him as a good student: „made some progress (1848), has ease – makes progress; second prize (1849), has made significant progress, but I believe that his musical organization does not allow him to go further; worker, made progress (1850), good musician – has ease – made significant progress (1851)“ In 1849 Doudiès wins a second price, two years later he finishes his studies with a first price. After his studies he stays a little while in Paris. He is member of the Association des artistes musiciens and plays in concerts here and there. In 1854 settles in Nantes where he gets appointed first flute at the Grand-Théâtre. He does not only fulfill his orchestra duties but organizes concerts, plays flute in a military band and conducts an amateur orchestra. As soloist he plays music by his colleagues (fantasies sur La dernière pensée, La Muette de Portici, a Grand Solo by Tulou, the fantaisie sur Robert le Diable by Walckiers, Souvenir de Paganini by Cottignies a.o.) as well as his own arrangements and compositions (Fantaisie pastorale concertantes, Réveil du Rossignol, fantaisie sur La Traviata, Le cor des Alpes, Une chanson dans le Bois for voice and flute, Romance and Malborough air varié for piccolo with accompaniment of harmony band). I did not find any of these compositions nor did I find any information about whether his works were published.

Doudiès’ compositional ambitions were not restricted to flute music. He also composed at least three operettas. Croix de Pierre was performed in Nantes in 1860 and Fleur de Genêt in 1862. The ouverture of another opera Wadah was performed in Nantes in 1862 by a military band, conducted by Doudiès. The operettas did not have the succes Doudiès might have wished. In his book Le théâtre à Nantes depuis ses origines Ètienne Destranges writes in 1893 „Croix de Pierre (…) This work proved that in M. Doudiès the composer was far from equaling the flute player” (p.328) and “Fleur de Genêt (…) operetta by M. Doudiès, whose first failure had not discouraged him“ (p.338). None of these works have been published.

In the 1860s he is appointed flute teacher at the conservatory in Nantes. He holds this post until after 1890.

Only little is written about his playing. On July 22 1861 a critic writes in the Nantes newspaper La Phare de la Loire “He draws very pure tones from his flute and makes steady progress. Two solos of his composition made it possible to appreciate the sureness of a playing that the study strengthens unceasingly. His concert piece entitled Réveil du rossignol is full of difficulties which he overcomes with great happiness and accuracy.”

Auguste-Dies-Charles Brivady was born in Perpignan on 29 November 1830. He joins the flute class at the age of 17. Brivady is not a very good student and seems to loose his motivation by the end of his studies. Tulou reports: „made significant progress; has made significant progress on the flute but is still a poor reader (1848), has only recently joined my class. I am satisfied with his attitude and I hope to have a good student; has made progress – is not a good musician and reads with difficulty; second prize, made progress on his instrument but still remained a poor reader (1849), could have made much more progress if he had not been lazy; progress is insensitive, very inaccurate to class; poor organization, made very little progress (1850).“ He does, however finish his studies after four years. There is only little information about his further career. A necrology in Le Ménestrel of 10 April 1904 gives us a few hints:

“From Geneva they announced the death of a French artist who had been very distinguished for many years, established in this city, Charles Brivady, who had made a brilliant position there. Auguste-Dies-Charles Brivady, born in Perpignan on November 29, 1830, had been admitted to the Conservatory in the class of Tulou and had obtained the second prize for flute in 1849 and the first in 1851. After having belonged for some time to the orchestra of the Porte Saint-Martin theatre, he had gone to settle in Geneva, which he never left. A very brilliant virtuoso, he was a member of the theater orchestra and of subscription concerts for a long time, then became a professor at the Conservatoire, where he trained many (une pléiade) of excellent students.“

Eugène-Jean Devalois, born on 10 June 1826 in Paris, was 27 years old when he won the first price at the 1853 concours. He is the oldest documented student of Tulou’s class who finished their studies. His studies have not been without problems. He was already 19 years old when he began his studies at the Conservatoire. Tulou did not take him into his class quite voluntarily as we can read in his report from 2 December 1845. He notes: „is too old to give any hope, and above all is too little of a musician. I have kept him in the class only to satisfy the desire of the Director [Auber] and to be agreeable to the [Louis-Auguste-Michel Félicité Le Tellier?] Marquis de Louvois.“

The Marquis de Louvois was no stranger to the art world (he died in 1844, so it is strange that Tulou still felt obliged to him, or was this obligation to his nephew?). He organised concerts in his house and was a member of the “commission spéciale des théâtres royeaux” as well as of the committee of the “association des artistes-musiciens”, an association that supported poor musicians. Auber was also a member of the committee, Tulou was one of the vice-directors. Moreover, he was a loyal royalist, so it probably seemed impossible to refuse such a request.

Tulou’s concerns did not change significantly over the years, as the following reports show: „low in all; bad musician. Fair sound quality; but very difficult fingers (1846), bad musician – heavy fingers, no facility in execution – little hope (1847), little progress despite his zeal to work, goes to great lengths, without result (1848), poor musician and not very good at playing the flute, still the same – weak, his progress is still slow despite his good will (1849), despite his efforts, his progress is not very noticeable, its progress is not very significant (1850), he is a student who follows the lessons of the Conservatory with accuracy. He works hard, but his progress is slow. (1851)“

In summer 1851 Devalois finally won a second price. This seems to have given him a boost, because the following year Tulou noted: „Zealous student; has made some progress this year (1852)“ In 1853, the time had finally come and Devalois was allowed to take part in the concours. Tulou wrote in the report: „follows my class with zeal – makes good progress“, but later also „zealous student; but his progress is not very noticeable (1853)“. Against all odds, Devalois received a first prize. He fought his way through and completed his studies, not everyone succeeded in this.

His career after graduation is hardly documented. Devalois no longer appears in the press. According to Constant Pierre he later played in the Orchestre du Théâtre Lyrique.

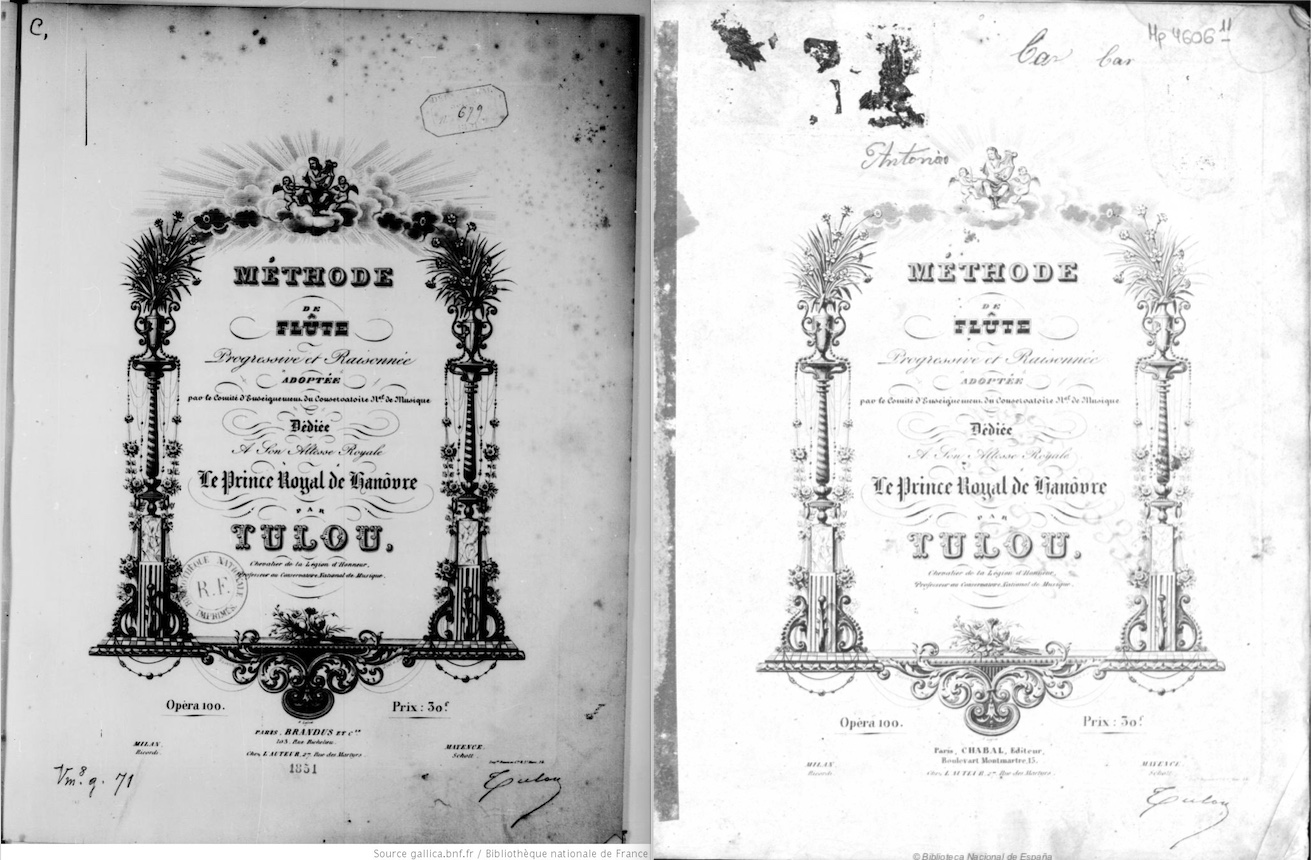

1851 is a special year for Tulou in many respects. In the summer, he publishes his long-awaited flute method op. 100. There is still much conjecture about the correct year of origin of the method, but in fact there is no longer any doubt that it is 1851. The method was published by at least three publishers: Chabal, Brandus & Cie and Schott (with a German translation). The Chabal and Brandus & Cie editions differ slightly from each other. The content is the same, but four pages with scales have different page numbers. In her dissertation about Tulou Michelle Tellier quotes a letter from Tulou to the engraver Benoit dated Sunday 4 May (the year is not mentioned, but in 1851 4 May was a Sunday) that two plates with trill charts still had to be engraved (these two trill charts are missing in the Brandus & Cie edition in National library in Paris (bnf). Benoit is the engraver of the method, he is mentioned on the front page below.

The Chabal edition could be purchased at “Editeur, Boulevard Montmarte, 15th” or “Chez L’AUTEUR, 27th Rue des Martyres”, where Tulou lived. Chabel moved to this address in 1849. Brandus&Cie moved to 103 rue Richelieu in 1851, the address on the Tulou method of their edition. So the publication date cannot be before 1851.

The method is clearly Tulou’s first one. In November 1850 Tulou wrote to the publisher Ricordi in Milan that he has been working on his method for the past 20 years, thus from 1830, his beginnings at the Conservatoire. He asked Ricordi to publish an Italian translation of his method. (I transcribed the four surviving letters by Tulou, you find them here.

There are two documents which could make us believe that there is another earlier method by Tulou:

An advertisement in the Revue musicale from 19 January 1834 mentions a “Devienne et Tulou – methode de flûte“ for the price of 18fl, a publisher is not added. A year later the publisher Aulagnier published a Devienne method with revisions of Ludovic Leplus and additional works by Kuhlau en Tulou. Does the Revue musicale refer to a Devienne method with added works by Tulou? Aulagnier must have published another Devienne method before 1828 as it is mentioned in a catalog by Whistling (Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur). It might be the same.

The second document is a letter from the administration of the Paris conservatoire to the administration of the Lille conservatoire from 12 November 1845 the writer gives a list of methods used for the education at the Paris conservatoire (cited in Giannini, Great Flute makers of France). The administration mentioned indeed a Tulou method, however, they also mentioned a trumpet method by Dauverné which has not been published before 1857. Was the Tulou method an unpublished document or the first version of his flute method? And if another method existed, why didn’t he mention it in his letter to Ricordi?

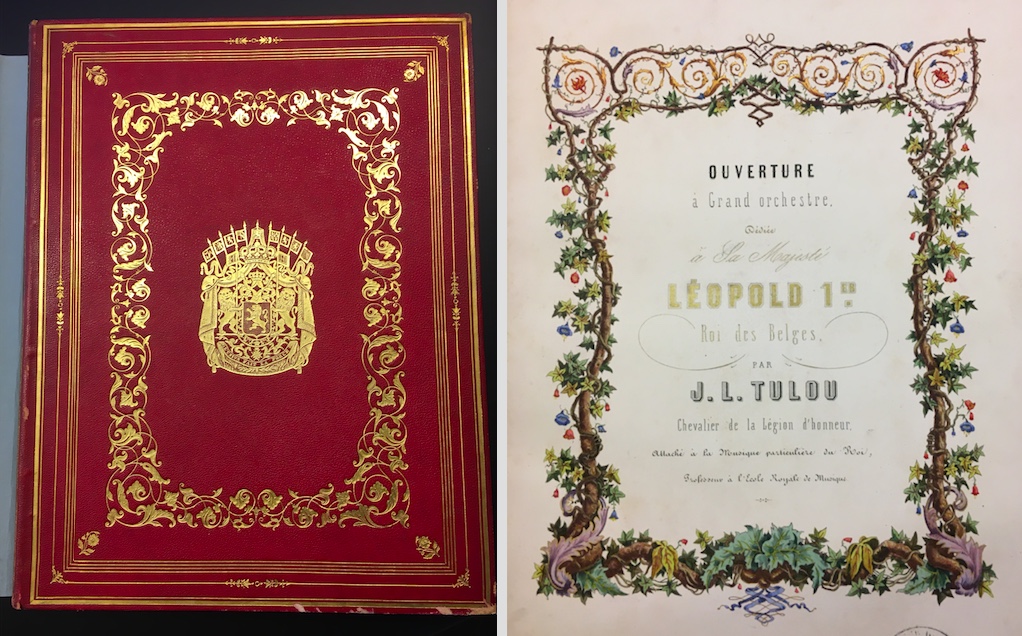

In October 1851, Tulou was honoured to receive a medal from the Belgian King Léopold I. He was now allowed to call himself Chevalier de l’Ordre de Leopold. For this occasion, Tulou composed what is probably the only orchestral work in his oeuvre, the Ouverture à Grand orchestre for harmony orchestra. He presented the beautifully designed manuscript, now in the library of the Royal Conservatoire in Ghent, to the King of Belgium.

The flute in this video is a flûte perfectionnée, made in Nonon’s workshop. Tulou announced his plan to perfect the flute as early as 1840 during the procès verbaux that took place to answer the question whether the Boehm flute should be taught in the Conservatoire. With this move he was able to convince the commission not to accept the Boehm flute at the Conservatoire for the time being. However, it should take ten years until the flûte perfectionnée came onto the market. Why? After the trial, Tulou was in a very comfortable situation. He won the trial. Victor Coche gave a very bad picture of himself and his model of the Boehm flute made by Buffet jeune, and Vincent Dorus, a rising star in the Paris flute world, adapted the conical Boehm flute (model 1832) to the ideal sound of Tulou. So for the time being there was no reason to continue to perfect the flute. In 1847 a new type of flute, the cylindrical Boehm flute, appeared that could become a lot more dangerous for Tulou. Unlike ten years ago, the Boehm flute in Paris followed just one standard model (in 1840 the commission criticized that there was no standard Boehm model). Tulou’s former criticism that the construction of the Boehm flute was not yet fully developed did not apply here. Furthermore, Dorus was now named in the same breath as Tulou, and if a Dorus was playing the new model, what’s to stop other flute players from doing the same? Tulou may have observed the situation for some time before stepping in and developing his own perfected flute. In 1851, he was already 65 years old, he published his “long-awaited” flute method and presented his new flute at the same time.

In 1856, Tulou reported in an article in the Revue musicale that the acoustics of the flute were completely recalculated and the bore and tone holes were adjusted. In the process, however, it did not lose the flute’s original sweet tone. Compared to the cylindrical Boehm flute, the tone is indeed more mellifluous. Nevertheless, his flûtes perfectionnées have a more powerful tone than their predecessors.

Jacques Nonon has been the foreman of Tulou’s workshop for more than 20 years when in 1853 he decides to leave and open his own workshop. (I recommend to read the article by René Pierre on flutes by Tulou and Nonon in his blog. He has done fabulous research on that matter!) At the moment it is impossible to put a year on the flute I play in the video. It could have been made before 1854. However, there are similar flutes that can be dated much later. Its key system differs slightly from Tulou’s flutes but does not have all improvements that Nonon patented in 1854. The stamp does not bear the patent mark (brevet). Here, he places the F#, short F- and low D#-keys on rods. The Bb- and short C-key are separate.