1859 – Tulou, 15e Grand Solo, op. 109

AJ/37/276 Archive Nationale de la France

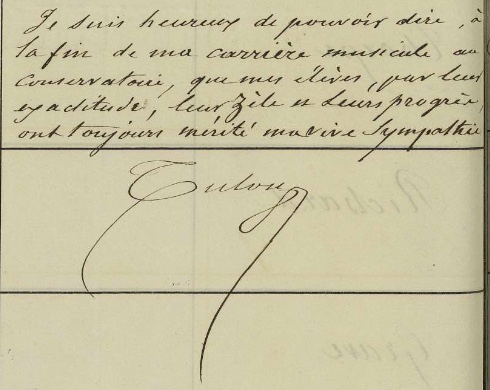

“Je suis heureux de pouvoir dire, à la fin de ma carrière musicale au Conservatoire, que mes élèves, par leur exactitude, leur zèle et leurs progrès ont toujours mérité ma vive sympathie. Tulou” – “I am pleased to be able to say, at the end of my musical career at the Conservatoire, that my students, by their accuracy, their zeal and their progress, have always deserved my deep sympathy. Tulou.”

These are the last words Tulou writes in the class reports on 3 November 1859. At the age of 73, after 31 years, he leaves the institution where he has spent a great part of his life. A photo from the 1860s shows him as a stately, authoritarian figure with a high-necked collar and a prosperous belly. He looks into the camera examiningly and somewhat sceptically.

Photograph by Carjat & Cie., Paris, musée Carnavalet.

The 15th Grand Solo is the last of 19 works that Tulou writes for his flute class. Structurally, it is similar to the other Grand Solos: two themes in a faster tempo, each followed by virtuoso passages, in the middle of the piece a slow part in a more distant key, a recapitulation of the first theme and a virtuoso ending. Of course, he did not forget the obligatory difficult trill passages. Here is the second theme, a beautiful light and elegant melody.

In his final year, Tulou has a relatively large class of nine students. As in previous years, he also teaches members of the military in addition to the ordinary students. Three of them are taking part in this year’s concours. Tulou’s year of departure coincidentally comes at the same time as the decision to standardise the pitch in France. In his speech at the distribution of the prices, Jules Pelletier, State Councillor, Secretary General of the Ministry of State, delegated for this purpose by His Excellency the Minister of State and of the Household of the Emperor, mentions the great achievement of establishing a uniform tuning pitch (diapason normal) for the whole country.

„Music has the privilege of being the only universal language to date. All civilised peoples speak of it, and the savage peoples themselves understand it. The number and inequality of pitches tended to destroy this almost divine character of music, and would make so many dialects irreconcilable by the difference of intonation and accent. It was worthy of the country which so gloriously symbolises progress and unity to try to put an end to this musical anarchy.“ (Revue musicale 7 August 1859)

Pelletier’s martial language is no mere coincidence. France is currently fighting in the Sardinian War on the side of Sardinia against Austria and on 11 July was able to conclude the preliminary peace of Villafranca. This victory was also duly honoured in the ceremony at the Imperial Conservatoire by the presence of General Mellinet who „had hastened to take his place in the office as the person in charge of the general inspection of military music students, and his entrance had been the object of a warm ovation“.

Paul Smith continues to report on the competitions and their prize winners in his article:

„The session devoted to wind instruments, which lasted twelve full hours a year ago, lasted only ten this time: progress is being made. Here is the list of students who have obtained nominations in these various competitions. Flute: teacher, Mr Tulou. – No first prize. 2nd prize, M. Trousseau. 1st accessit, M. Richard; 2nd accessit, M. Feillou; 3rd accessit, M. Crave.“

As always, the wind instruments are only briefly mentioned, only the newly added classes for valve trombone and the saxhorn get a short description.

Charles-Cyprien Trousseau, was born in Belleville / Paris on 30 May 1840. When he was admitted to Tulou’s class in 1856, the latter was not particularly enthusiastic. Tulou notes in the semi-annual report: “This young man was presented to me by Cariot, professor at the Conservatory, with a request to admit him to my class, without this recommendation I would not have received him.“

Trousseau slowly makes progress, but the relationship between pupil and teacher seems to be difficult. Already the following year, Trousseau takes part in the concours. Tulou reports: “the state … of this pupil, recommend him to the benevolence of the Director, enough facility of execution; strength in the sound; but with him the style and the musical taste, have difficulty in developing”.

Trousseau gets a 1e accessit. In the following year, Tulou reports: “has made progress, but does not read music with ease, has made satisfactory progress this year” (1858), “fairly easy to perform; but little musical feeling” (1859).

Despite everything, Trousseau received a 2e prix in 1859. Better times began for Trousseau with the new teacher Dorus, who was so pleased with his playing abilities that in 1860 he asked the director to give him and Henry Thorpe an extra year because of the change to the Boehm flute, since both were good students and had a good disposition. In 1862 he finally wins a first prize. Nevertheless, Trosseau will not pursue a flute player career. Instead, he joins his father’s business running the Élysée-Ménilmontant, an inn with dancing and concerts in the vast gardens of Belleville-Saint Denis, and will take over the management in 1891.

Louis-Eugène Richard was born in Douai on 19 Decembre 1839. He entered the Conservatoire at the age of 17. Richard is a good student as Tulou reports: “has made a lot of progress in spite of the short time he has been in my class, poor musical organisation, has made a lot of progress, very exact (?) in class (1858), zeal, works a lot; progress, but slow. (1859). Dorus gives him a good report as well: „good worker, full of good will, has much to do to improve his sound quality; Good. (1860)“. In 1861 he gets a second price for the flute and a first price for solfège. For unknown reason Richard does not finish his flute studies with a first price. I could not find any information about his further career.

Etienne-Hubert Feillou was born on 1 January 1839 in Paris. He is one of the students sent by the military to the Conservatoire to improve their playing. He probably only stays in Tulou’s class for two years. In the second year of his studies, he takes part in the concours and wins a 2e accessit, after which his trail is lost. Another Feillou, Charles-Évariste-Etienne, born in 1862 in Toulouse, studied flute in Paris as well. He received a first price in 1881. His father Jean Feillou was musician as well. It is not known whether there are family connections bewteen both Feillous.

Albert-Joseph Crave, born on 20 April 1840 in Lille, comes from the military as well. He enters the Conservatoire in 1858 and gets a third accessit in 1859. Tulou speaks very positively about him: “very zealous; has made good progress, has made a lot of progress in the last 6 months (1858), can compete this year; would have made more progress if he had not been ill often (1859)“. There is no information about his further career.

The five-keyed flute in this video was made in the workshop of Isidore Lot. As the name suggests, Isidore is part of the famous Lot family in La Couture-Boussey. Around 1856, he opens his own workshop and runs it until 1885. In a report on the Exposition universelle of 1867, M. de Pontécoulant writes that Isidore manufactures mainly woodwind instruments with ordinary system (systême ordinaire). In the Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce from 1857, Lot describes his assortment as follows: “Boehm flutes and oboes with a new mechanism, ordinary flutes in C or B, old and new system; Boehm and 13-key clarinets, flageolets, etc.”

The tone of the flute is, as with many French flutes, light and aspiring to the treble. However, it is noticeable that it no longer has the tonal qualities of earlier instruments. The larger tone holes and the somewhat larger embouchure hole give it a larger tone, but on the other hand the tone loses its mellowness and the intonation of the fork fingerings deteriorates. For example, the fork F is very high in all octaves. Since the flute does not have a long F key, it is not a great pleasure to play in flat keys and there are no alternatives in situations like the following.

Furthermore, the edges of the tone holes are not rounded as usual and cut into the fingers after long playing. This flute was certainly not intended for professional use; it rather belonged in the hands of an amateur.