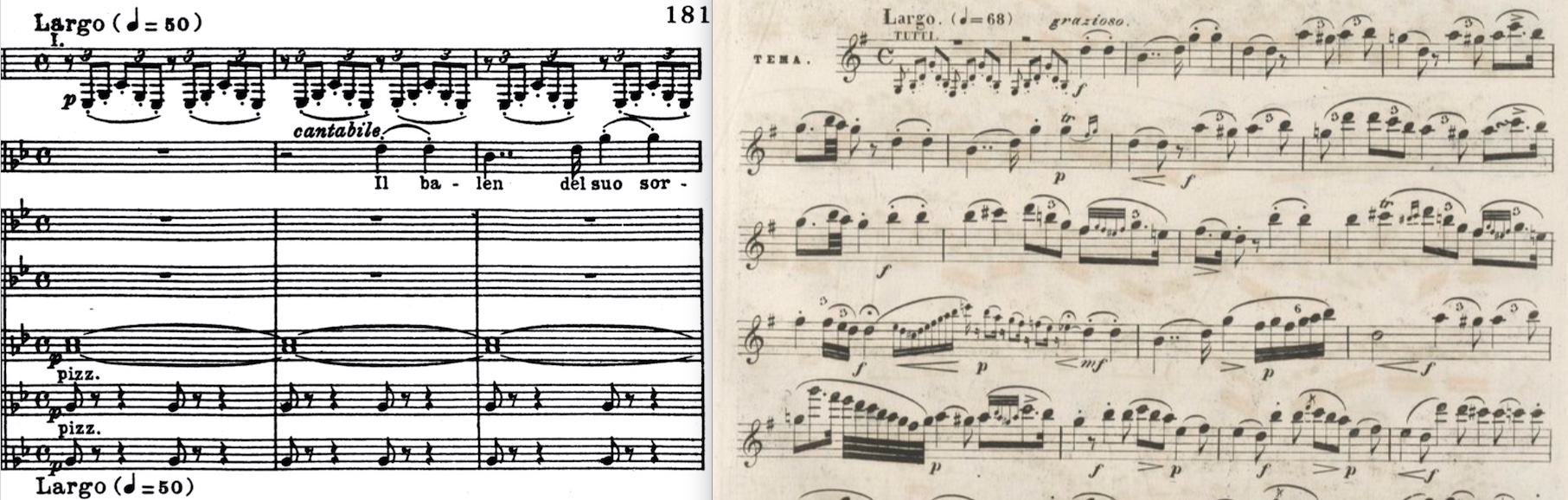

1856 – Tulou, Fantaisie sur Il Trovatore op. 105

The opera Il Trovatore by Giuseppe Verdi was first performed in Paris at the Théâtre-Italien in December 1854. It was an immediate success and was programmed many times in the following years. Tulou chooses the aria Il balen del suo sorriso for his fantasy. In this aria (Act 2 no. 7), the Count of Luna (baritone) sings of his love for Leonora, who has entered a convent after hearing of the death of her lover Manrico.

The flashing of her smile

shines more than a star!

The radiance of her beautiful features

Gives me new courage!…

Ah! Let the love that burns inside me

speak to her in my favour!

Let the sun’s glance clear up

the tempest raging in my heart.

Tulou takes over most of the articulation and ornamentation from the original text, but changes the metronome figure given by Verdi from MM. 50 to 68 per quarter note.

Tulou dedicated the fantasy to Major Sir Warwick Hele Tonkin, a British nobleman who owned an apartment in the centre of Paris, 21, place de la Madeleine. He was one of the (vice-) presidents of the Société Universelle pour l’Encouragement des arts et de l’Industrie, founded in 1851 and based in London. Goal of the society was to „encourage the arts and industry of the entire world. The patrons of the Society are sovereigns, heads of government, and ambassadors: the title of honorary president is offered to men who have acquired just fame by their work and discoveries. The Society awards numerous prizes and encouragements, and publishes monthly in a special journal, entitled Annales de la Société universelle, reports, useful information, inventions and productions of all kinds.“ (Revue des sociétés savantes de la France et de l’étranger, Paris1854, p. 318)

In 1856, two students took part in the concours:

Jean-Baptiste-Marie (also Johannès) Donjon was born in Lyon on 5 August 1839. Both his father Alexis and his grandfather François Donjon played the flute in the local theatre. It can therefore be assumed that Johannès first learned to play the flute from them. At the age of 14, he joined Tulou’s flute class. He is a very good student, as Tulou reports: “He will become, I hope, the best pupil in my class (1855), a very distinguished pupil; an excellent pupil (1856)”. Already in the second year of his studies he takes part in the concours and receives a second prize. The following year his father died, Donjon was only 16 years old. Perhaps the death of his father was the reason why Donjon skipped the concours that year and did not take part again until a year later. In 1856, he was awarded the first prize. Tulo may not have been Donjon’s only flute teacher, as he plays together with Firmin Brossa and Taffanel Quartett with Eugène Walckiers, a popular teacher and author of a highly informative Method for the Boehm flute (1829).

After his studies, Donjon probably began to play, like many of his colleagues, in the Concerts Pasdeloup, an orchestra that engaged young laureates of the Conservatoire. On 7 April 1861, his name appeared in a concert review of the Revue Musicale. The verdict on his playing was very positive:

“M. Donjon, who, if we are not mistaken, belongs to the beautiful and pure school of Tulou (…) have above all satisfied the delicate intelligences and contributed to making us forget the insignificance, to say the least, of the rest of the vocal part.

Donjon plays in the Orchestre du Vaudeville, exactly when is impossible to say. According to Blakeman (Taffanel, Genius of the Flute, 2005) Donjon played in the Opéra Comique. I could not find any proof of this. In 1866 Donjon becomes a member of the orchestra at the Opéra. There he plays the third flute next to Ludovic Leplus and Henri Altès. In 1876, when Altès retires, he is given the post of second flute between Taffanel and Lafleurance. With the post at the Opéra, Donjon reaches the highest level an orchestral musician could reach in Paris. It is probably no coincidence that all the flute professors of the Paris Conservatoire (Wunderlich, Guillou, Tulou, Dorus, Altès and Taffanel) were principal flutists in this prestigious orchestra. The post at the Opéra is also the ticket to higher musical circles. Compared to his fellow students, Donjon plays in an exceptionally wide range of concert series. He seems to be particularly fond of chamber music. Over the years, he builds up a varied repertoire and performs with different chamber music partners. His concert repertoire includes sonatas by Handel, Kuhlau (with orchestral accompaniment!) and Walckiers, duos by Gattermann and Demersseman, trios by Berlioz, Lavignac and Adolphe Blanc, quintets by Mozart, Reicha, Rubinstein and Taffanel, and septets by Hummel, Widor and Blanc. Even before Taffanel, in the autumn of 1869, Donjon founded a Société musicale pour l’exécution de quintettes harmoniques with his colleagues Triébert (oboe), Turban (clarinet), Garigue (horn), Lalande (bassoon) and Populus (organ or piano). The first concert takes place on 2 December. We find information about the ensemble’s repertoire in an advertisement in the Ménestrel of 14 January 1872:

“The Société des quintettes harmoniques will resume its chamber music sessions on the third Saturday of each month, beginning on 20 January 1872. This Society, founded in 1869, in the Salle Gay-Lussac, rue Gay-Lussac no. 41 bis, by Messrs: Donjon, flutist; Triébert, oboist, Turban, clarinet, Garrigue, horn of the Opéra-Comique, Lalande, bassoon of the Concerts populaires, and A. Populus, maître de Chapelle, organist, has already made known, and we must congratulate him for this, in addition to the masterpieces of Beethoven, Mozart, Reicha and Weber, several works by modern composers such as A. Blanc, C. Saint-Saëns, Barthe etc. Good luck for classical music lovers who will come to the Gay-Lussac hall.”

The classics are not always well received. In 1875, Reicha’s quintet receives “a rather cold reception” (Annales du théâtre et de la musique 1876, 534). However, Donjon has particular success with an old master. In 1873 he plays a

“fragment of a superb flute sonata by Handel, masterly rendered by M. Donjon. Hearing this last work gave me the idea of doing some research on the sonata, I will give some information on this form of instrumental music, which has been neglected for many years,”,

reports the newspaper Le Soir on 20 May. Donjon will regularly perform Handel’s sonatas in concerts for many years to come. In 1880, the Revue du monde musical et dramatique ( vol. 3 138) writes:

“A session entirely devoted to instruments, even to wind instruments, took place at the Salle Pleyel, with the assistance of M. Donjon. The performance was perfect in every respect; one would have thought one was at the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire; and besides, what wonder, since the performers were Messrs Taffanel, Donjon (flutes), Gillet, Boullard (oboes), Grizez, Turban (clarinets), Garigue, Dupont (horns), Espaignet and Bourdeau (bassoons). The one and only solo was given to the flute in a Handel sonata, which M. Donjon played with the purity of sound and delicacy of style that are familiar to him; M. Diémer played the piano.”

Concerts such as these are mainly organised for a more discerning audience, and the events take place within the framework of the Société des Beaux-Arts, Société de musique Classique, Société des Concerts or Société des compositeurs. The concert events are called Enfant d’Appollon, Petit Bayreuth or Concerts du Grand-Hôtel.

However, the musicians of the Opéra do not only play music of the highest standards. They can also be found in more popular concert series such as that of the Jardin zoologique d’acclimatation, a zoo inaugurated in 1860 by the then Emperor Napoleon III and home to over 100,000 animals. The concerts take place on Thursdays and Sundays at 3pm during the concert season. Their programme is similar to those of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées, entertaining orchestral music paired with solo performances by individual musicians. Between 1872 and 1880, Donjon, like his quintet colleagues, performs regularly in this concert series, mainly with the piccolo. He composes his own works for this occasion, such as Valse or Le Zizi for one piccolo or duo, Tracoline or Rondo for two piccoli and orchestra. He also plays works by other composers, such as Le Colibri by Adolphe Sellenick or Le Rossignol by Louis-Antoine Jullien.

From 1880, when he is 41 years old, his name appears much less frequently in newspapers and he performs less often in concerts. In his place, his colleague Lafleurance, third flute at the Opéra, now regularly appears in concerts in the Jardin zoologique d’acclimatation and plays Donjon’s works for piccolo. The reason for this could be Donjon’s appointment as the first flutist at the Opéra and an associated increase in salary. From 1881 onwards, he is mentioned in concert reports as the Opéra’s first flutist. It is possible that he shared the post with Taffanel; more research would need to be done on this. Donjon also taught at the école Rocroy-Saint-Léon, as evidenced by the following article in Figaro on 7 May 1883:

“A touching ceremony brought together, yesterday, at the Rocroy-Saint-Léon school, the parents and pupils of this establishment. On the occasion of the first communion, a solemn greeting was sung in the chapel of the institution, decorated for the occasion with perfect taste and great magnificence. M. Donjon, principal flute of the Opera and teacher at the institution, lent the assistance of his remarkable talent to this family celebration, which was wonderfully successful.”

In 1890, at the age of only 51, he ended his work at the Opéra. According to several sources, he died in Paris in 1912.

Marie-Joseph Duvergès (also Duverger) was born in Auch (South of France) on 3 October 1838.The circumstances when and why he was sent to Paris are not known. Perhaps he showed talent on the flute, perhaps the family sent their son to the military school in Paris. He is already 18 years old when he enters Tulou’s class in 1855. He does not take part in solfège, nor in harmony lessons, so he must have received musical training beforehand. Tulou is pleased with him. He reports:

“ease, fairly good musician but the embouchure a little hard (21. January 1856); has made much progress, can compete this year (18. June 1856)”.

Duvergès receives a first accessit. It will be the only concours in which Duvergès takes part, as he leaves the Conservatoire the following year. Tulou tells us why:

“very good pupil; but having been obliged to take a place as a petite flute in a regiment, it is to be feared that our hopes of his future talent will not be realised”.

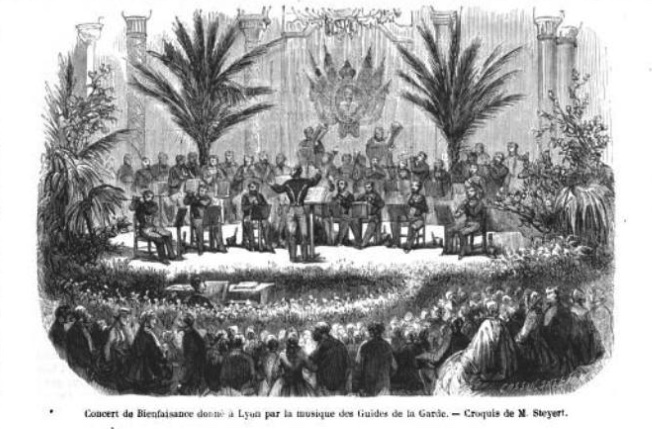

At first, the talent seems to have been lost. However, Duvergès was given the opportunity to join a special guard, the Musique des Guides de la Garde Impériale. This was founded in 1852 as the musical showpiece of the new Emperor Napoleon III. In addition to the usual brass instruments of trumpet, horn and trombone, it consists mainly of the instruments newly developed by Adolphe Sax plus some woodwinds (flute, oboe, clarinet). The harmony orchestra not only plays on official ceremonial occasions, but also performs for the people as depicted in the L’Illustration, Journal Universel (24e année, vol. XLVII, p.220).

From November 1862, various newspapers report on solo performances by Duverger. He mainly plays light music, airs variés, fantaisies duos with oboe. The opinions about the young flute player are consistently positive, if one is to believe the newspapers:

“(…) a final piece for the flute, composed by that other great artist who is called Duverger. (Feuille de Provins 22. November 1862),

“We have especially enjoyed a delicious theme on which the flute of M. Duverger makes its silver notes vibrate in the happiest way. (Journal de Seine-et-Marne, 17. November 1866).

“A new fantasy on Moïse, (for two octave flutes) (…) in which Messrs Fabre and Duverger let the delicious timbre of their instrument shine, was received with enthusiasm by part of the audience: it is the intelligent part that we want to speak of and not the one whose sole purpose seems to be to cover the voice of the soloists with the noise of intimate chatter. (…) You know Cherubini’s words: “I know nothing more boring than a flute piece, except a piece for two flutes’; The illustrious director of the Conservatoire would certainly not have made this joke if, like us, he had heard, through the melodic ideas of the theme of this Swiss air, the dazzling cackling of carried away lines, of trills beaten with precision and incomparable equality, chased in their turn with proud ardour by the scales in double tongues, which also came to seize the little instruments with an admirable power of vibration and accuracy, you would have said two imps chasing each other and making a thousand hooks and a thousand turns to avoid each other in the air. ” (Journal de Seine-et-Marne, 23. März 1867)

“A large part of the honours of the session went to Duverger and Triébert. These two virtuosos performed a duet by Gattermann, for flute and oboe, with grace, clarity, a surprising certainty of intonation, and an admirable manner of phrasing. They received the loudest applause, thanks to the lines they played with marvellous ease and agility. (Journal de Seine-et-Marne, 30. März 1867).

An attempt to bring more serious chamber music to the people achieved little success, as can be read in the Journal de Seine-et-Marne on 2 March 1867:

“One fact that we have observed in these musical sessions is the public enthusiasm that the soloists generally receive, while the ensemble pieces are, for the most part, only greeted with indifference, not to say coldness. Of course, it is not we who will protest against the applause given to virtuosos who are not afraid to face the perils of the stage in order to show off on their instrument in front of an audience of varying degrees of expertise, especially when they know how to display such brilliant qualities of style and mechanism as (…) M. Duverger did in an air varié for flute. But do you think that the instrumentalists of the orchestra do not deserve such a just appreciation and such warm admiration when they perform, as they did last Sunday. The first piece, a trio by Beethoven for clarinet, flute and oboe, called Messrs Fabre, Duverger and Triébert to the podium. Here we must, in spite of all, pause to note the superiority of ensemble and precision with which this magnificent page, though perhaps a little severe for the audience, was performed by the eminent artists we have named.“

In 1867, the Musique des Guide de la Garde Impériale was disbanded due to its high cost and insufficient usefulness in wartime situations. The musicians were either distributed among other regiments or lost their posts, as did Duvergès. Through fortunate (for him) circumstances, Duvergès immediately found another job. With Demersseman’s death in December 1866, the Champs-Elysées concert series lost one of its stars. By chance, in the spring of 1867, the Musique des Guides open the season of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées and performed every evening from 18 April to 1 May, and every Friday evening thereafter. The concerts are a great success. Duvergès plays several solos on the large and small flute during this period. In this way, the conductor of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées may have come to know and appreciate Duvergès’s playing, so that the latter is given the position of flute in the following seasons. Duvergès played in the Concerts des Champs-Elysées until at least 1871. The repertoire has changed a little since Demersseman. Instead of the regular flute solos, one now hears works with variations on different instruments or works with solos by individual instruments, as for example on 21 August 1869 (picture advertisement in the Vert-vert).

In addition to the large flute, Duvergès plays works on the piccolo (petite flûte), mostly in duets with his colleagues Fabre or Forment. Titles of these works are Le Sansonnet, Polka by G. Daniel for one piccolo or Jeanne et Jeannette – polka de Duverger, quadrille de Musard père avec variations, Polka des Fauvettes avec variations de N. Bousquet for two piccoli and orchestra. The two little flutes are very well received by the public, as the following advertisement in the Journal de Seine-et-Marne of 23 March 1867 proves:

“A new fantasy on Moïse, (for two octave flutes) (…) in which Messrs Fabre and Duverger have made the delicious timbre of their instrument shine, has been received with enthusiasm by part of the audience: it is the intelligent part that we want to speak of and not that whose sole purpose seems to be to cover the voice of the soloists with the noise of intimate chatter. (…) You know Cherubini’s words: “I know nothing more boring than a flute piece, except a piece for two flutes’; The illustrious director of the Conservatoire would certainly not have made this joke if, like us, he had heard, through the melodic ideas of the theme of this Swiss air, the dazzling cackling of carried away lines, of trills beaten with precision and incomparable equality, chased in their turn with proud ardour by the scales in double tongues, which also came to seize the little instruments with an admirable power of vibration and accuracy, you would have said two imps chasing each other and making a thousand hooks and a thousand turns to avoid each other in the air.”

Incidentally, Cherubini’s quotation is a popular catch-all for newspaper reporters to put flute players in a positive light. Duvergès was also caught once again in the newspaper La Patrie on 15 March 1870

“Let me say a few words about the new compositions of M. Duvergès, the worthy successor of Tulou, the flautist who, reversing the saying, would make the person who asked answer: “What is more attractive than a flute?-Two flutes”, of course, if Duvergès could play two at the same time, like the ancient Greeks and Romans. But don’t worry, one is enough to charm you, especially if he performs one of his latest fantasies, such as the Souvenirs de la Tourraine, or those on Crispin e la Comare and Folie à Rome. If you have heard it, there is no need for me to speak of it; if not, well, hear it; you shall speak of it!”

In 1872 Duvergès published a method for the Boehm flute. He dedicated it to the director of the Conservatoire in Lyon, Edouard Mangin, who had been founded that year. Mangin studied in Paris at the same time as Duvergès. Did Duvergès hope to obtain a post as flute teacher in Lyon with this method?

He does not seem to have succeeded, for Duvergès remains in Paris. It is not known whether he will be engaged in the following seasons of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées. From now on, concert announcements with his name become rarer. In 1872 he appeared in the 9th Festival des théâtre du Châtelet, playing his variations on Ah! Je vous dirai-je, madame on the piccolo. In 1874 he appears in an all-evening concert series at the Concerts Frascati, then disappears.

It is not known when Duvergès died, but according to Goldberg it was in 1876 or 1877, at the age of only 38 or 39. Duvergès left behind a number of works that were still published after his death. All works, with one exception, were published by Léon Escudier.

Le premier jour de bonheur: opéra comique d’Auber: airs arrangée pour flûte seule, en deux suites (1868), Crispino e la comare (le docteur Crispin), opéra-bouffe des frères Ricci, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano (1869), Une folie à Rome. Opéra bouffe de Fred. Ricci. Fantaisie pour la flûte avec accompagnement de piano (1870), 4 Fantaisies pour flûte avec acc. de piano, Verdi (1872), Ah! je vous dirais-je Maman, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 25 (1872/73), Souvenir de Touraine, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 26 (1872), Au clair de la lune L. Escudier op. 27 (1872), Aida, opéra de Verdi fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 28 (1872), Bébé-polka pour le piano (1873), New and complete method or school for the cylindrical flute english translation by E. Salabert ( 1875), Nouvelle méthode complète de flûte Boehm cylindriue (1873), Le Roi l’a dit, opéra-comique de L. Delibes, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 30 (1873), Messe de Requiem de G. Verdi, pensée réligieuse pour flûte avec acc. de piano ou d’orgue-harmonium (1874), L’Hirondelle. Polka pour petite flûte Musique militaire (1877, ed. P. Goumas).

The twelve-keyed flute in this video is completely atypical of French instruments of the time. It has, for example, a metal-lined headjoint made of ivory, many keys and tone holes with metal decorations. Although it bears the French stamp “Truchot & Cie / Paris”, it was not made in France but imported from either Austria or Italy and sold by a dealer named Truchot & Cie in Paris. I found no traces of that shop in historical sources. A Maison Truchot in Paris made and restored felt of hammers for pianos but did not advertise for selling instruments.

The sound and playing style of the flute are of course atypical for France and follow the ideal of its place of manufacture. The tone holes are on slightly different positions, the left thumb has to be put left of the Bb-key, some notes sound better with ‘German’ fingerings (such as C”’ XOX/XOX/o instead of OXO/XXX/o), and the sound is very different. I wonder who bought that instrument at that time in Paris. Given the signs of wear that person must have played the flute very much. It’s indeed a wonderful instrument, just not French at all despite its stamp.

The piano is 1843 Pleyel.