AJ/37/276 Archive Nationale de la France

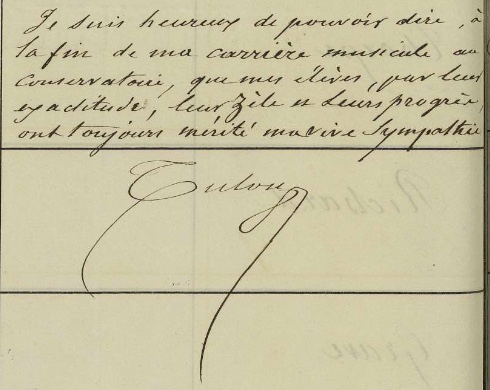

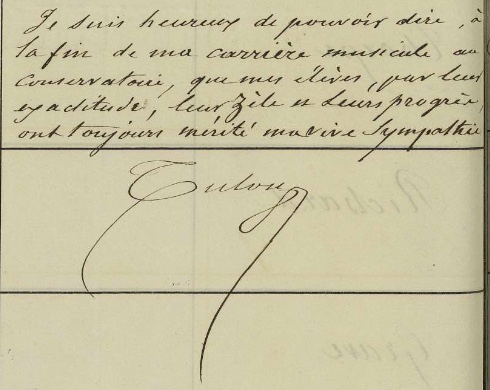

“Je suis heureux de pouvoir dire, à la fin de ma carrière musicale au Conservatoire, que mes élèves, par leur exactitude, leur zèle et leurs progrès ont toujours mérité ma vive sympathie. Tulou” – “I am pleased to be able to say, at the end of my musical career at the Conservatoire, that my students, by their accuracy, their zeal and their progress, have always deserved my deep sympathy. Tulou.”

These are the last words Tulou writes in the class reports on 3 November 1859. At the age of 73, after 31 years, he leaves the institution where he has spent a great part of his life. A photo from the 1860s shows him as a stately, authoritarian figure with a high-necked collar and a prosperous belly. He looks into the camera examiningly and somewhat sceptically.

Photograph by Carjat & Cie., Paris, musée Carnavalet.

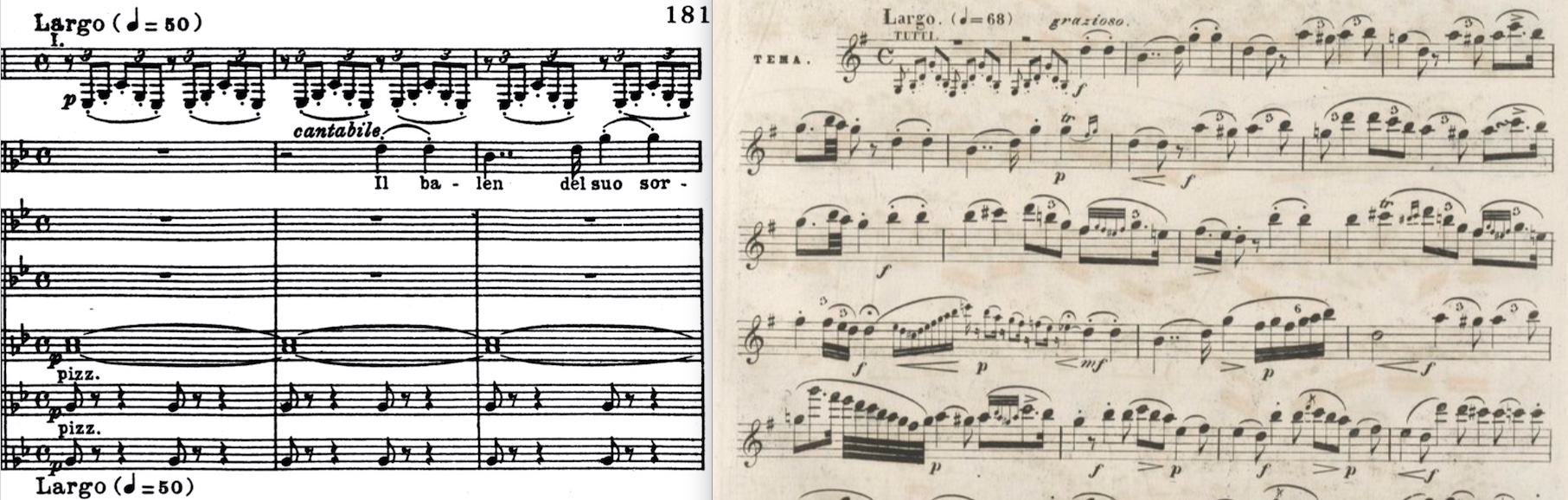

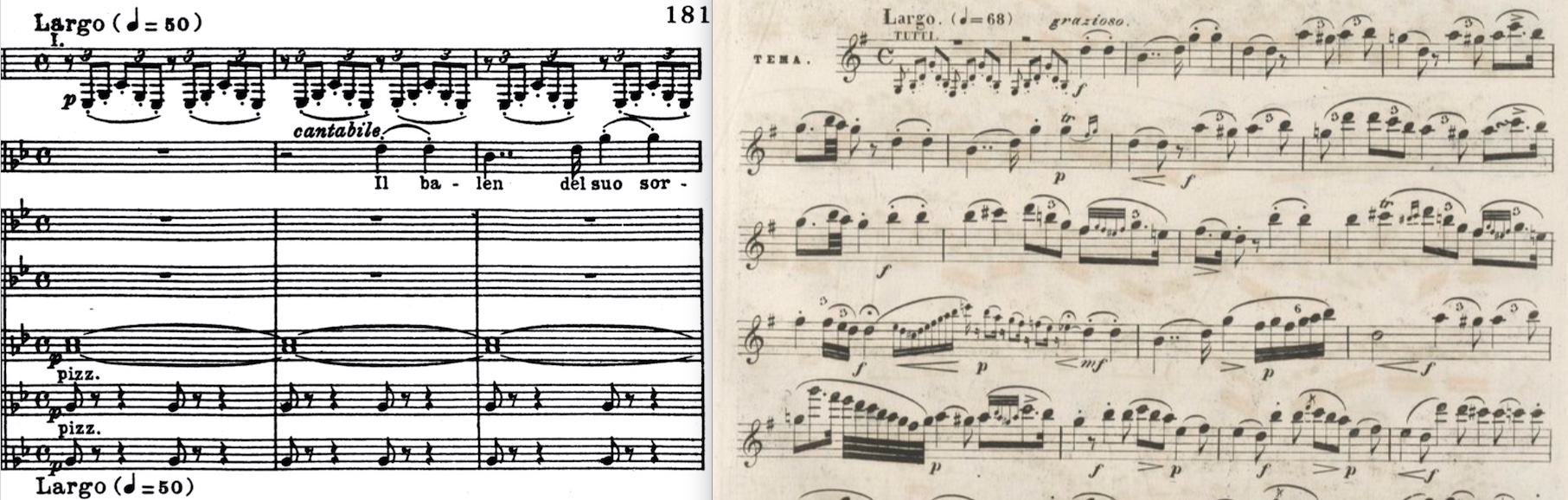

The 15th Grand Solo is the last of 19 works that Tulou writes for his flute class. Structurally, it is similar to the other Grand Solos: two themes in a faster tempo, each followed by virtuoso passages, in the middle of the piece a slow part in a more distant key, a recapitulation of the first theme and a virtuoso ending. Of course, he did not forget the obligatory difficult trill passages. Here is the second theme, a beautiful light and elegant melody.

In his final year, Tulou has a relatively large class of nine students. As in previous years, he also teaches members of the military in addition to the ordinary students. Three of them are taking part in this year’s concours. Tulou’s year of departure coincidentally comes at the same time as the decision to standardise the pitch in France. In his speech at the distribution of the prices, Jules Pelletier, State Councillor, Secretary General of the Ministry of State, delegated for this purpose by His Excellency the Minister of State and of the Household of the Emperor, mentions the great achievement of establishing a uniform tuning pitch (diapason normal) for the whole country.

„Music has the privilege of being the only universal language to date. All civilised peoples speak of it, and the savage peoples themselves understand it. The number and inequality of pitches tended to destroy this almost divine character of music, and would make so many dialects irreconcilable by the difference of intonation and accent. It was worthy of the country which so gloriously symbolises progress and unity to try to put an end to this musical anarchy.“ (Revue musicale 7 August 1859)

Pelletier’s martial language is no mere coincidence. France is currently fighting in the Sardinian War on the side of Sardinia against Austria and on 11 July was able to conclude the preliminary peace of Villafranca. This victory was also duly honoured in the ceremony at the Imperial Conservatoire by the presence of General Mellinet who „had hastened to take his place in the office as the person in charge of the general inspection of military music students, and his entrance had been the object of a warm ovation“.

Paul Smith continues to report on the competitions and their prize winners in his article:

„The session devoted to wind instruments, which lasted twelve full hours a year ago, lasted only ten this time: progress is being made. Here is the list of students who have obtained nominations in these various competitions. Flute: teacher, Mr Tulou. – No first prize. 2nd prize, M. Trousseau. 1st accessit, M. Richard; 2nd accessit, M. Feillou; 3rd accessit, M. Crave.“

As always, the wind instruments are only briefly mentioned, only the newly added classes for valve trombone and the saxhorn get a short description.

Charles-Cyprien Trousseau, was born in Belleville / Paris on 30 May 1840. When he was admitted to Tulou’s class in 1856, the latter was not particularly enthusiastic. Tulou notes in the semi-annual report: “This young man was presented to me by Cariot, professor at the Conservatory, with a request to admit him to my class, without this recommendation I would not have received him.“

Trousseau slowly makes progress, but the relationship between pupil and teacher seems to be difficult. Already the following year, Trousseau takes part in the concours. Tulou reports: “the state … of this pupil, recommend him to the benevolence of the Director, enough facility of execution; strength in the sound; but with him the style and the musical taste, have difficulty in developing”.

Trousseau gets a 1e accessit. In the following year, Tulou reports: “has made progress, but does not read music with ease, has made satisfactory progress this year” (1858), “fairly easy to perform; but little musical feeling” (1859).

Despite everything, Trousseau received a 2e prix in 1859. Better times began for Trousseau with the new teacher Dorus, who was so pleased with his playing abilities that in 1860 he asked the director to give him and Henry Thorpe an extra year because of the change to the Boehm flute, since both were good students and had a good disposition. In 1862 he finally wins a first prize. Nevertheless, Trosseau will not pursue a flute player career. Instead, he joins his father’s business running the Élysée-Ménilmontant, an inn with dancing and concerts in the vast gardens of Belleville-Saint Denis, and will take over the management in 1891.

Louis-Eugène Richard was born in Douai on 19 Decembre 1839. He entered the Conservatoire at the age of 17. Richard is a good student as Tulou reports: “has made a lot of progress in spite of the short time he has been in my class, poor musical organisation, has made a lot of progress, very exact (?) in class (1858), zeal, works a lot; progress, but slow. (1859). Dorus gives him a good report as well: „good worker, full of good will, has much to do to improve his sound quality; Good. (1860)“. In 1861 he gets a second price for the flute and a first price for solfège. For unknown reason Richard does not finish his flute studies with a first price. I could not find any information about his further career.

Etienne-Hubert Feillou was born on 1 January 1839 in Paris. He is one of the students sent by the military to the Conservatoire to improve their playing. He probably only stays in Tulou’s class for two years. In the second year of his studies, he takes part in the concours and wins a 2e accessit, after which his trail is lost. Another Feillou, Charles-Évariste-Etienne, born in 1862 in Toulouse, studied flute in Paris as well. He received a first price in 1881. His father Jean Feillou was musician as well. It is not known whether there are family connections bewteen both Feillous.

Albert-Joseph Crave, born on 20 April 1840 in Lille, comes from the military as well. He enters the Conservatoire in 1858 and gets a third accessit in 1859. Tulou speaks very positively about him: “very zealous; has made good progress, has made a lot of progress in the last 6 months (1858), can compete this year; would have made more progress if he had not been ill often (1859)“. There is no information about his further career.

The five-keyed flute in this video was made in the workshop of Isidore Lot. As the name suggests, Isidore is part of the famous Lot family in La Couture-Boussey. Around 1856, he opens his own workshop and runs it until 1885. In a report on the Exposition universelle of 1867, M. de Pontécoulant writes that Isidore manufactures mainly woodwind instruments with ordinary system (systême ordinaire). In the Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce from 1857, Lot describes his assortment as follows: “Boehm flutes and oboes with a new mechanism, ordinary flutes in C or B, old and new system; Boehm and 13-key clarinets, flageolets, etc.”

The tone of the flute is, as with many French flutes, light and aspiring to the treble. However, it is noticeable that it no longer has the tonal qualities of earlier instruments. The larger tone holes and the somewhat larger embouchure hole give it a larger tone, but on the other hand the tone loses its mellowness and the intonation of the fork fingerings deteriorates. For example, the fork F is very high in all octaves. Since the flute does not have a long F key, it is not a great pleasure to play in flat keys and there are no alternatives in situations like the following.

Furthermore, the edges of the tone holes are not rounded as usual and cut into the fingers after long playing. This flute was certainly not intended for professional use; it rather belonged in the hands of an amateur.

Plaisir d’Amour was very popular and widely known in France in the 19th century. Today, most people probably know the piece in Elvis Presley’s version (Can’t help falling in love). The romance has its origins in the 18th century. Jean-Paul-Égide Martini wrote it in 1784, at that time it was entitled Romance du Chevrier. For the text, he used a romance from the novel Célestine, nouvelle espagnole from the collection Les six nouvelles de M. de Florian by Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian.

Various arrangements of the song were written in the 19th century. In 1829, a few years before Tulou, Berbiguier wrote flute variations on this song (Fantaisie avec Variations op. 91). One year after Tulou, Berlioz wrote a version for baritone and orchestra.

The composers chose different indications for their works. Martini marked it Romance. doloroso, Berbiguier chose Andante lento /dolce, Tulou molto lento, and Berlioz wrote Adagio. Tulou probably copied the term from the songbook Échos de France, recueil des plus célèbres airs, romance, duos etc., published by Durand & Fils in 1853 (p. 88, picture).

With his indication, Tulou probably chose a relatively slow execution. The slow tempo benefits the first variation, which he wants in the same tempo. Before the theme with variations in F major, Tulou sets two introductory parts, beginning with a recitative and followed by an Allegro moderato. Both introductions are wonderfully suited to freer rubato playing. The theme is followed by three variations in different characters, a graceful first variation followed by a staccato variation and a third poco animato variation with virtuoso passages. The finale is a polonaise in D major. In the middle of this finale, Tulou briefly flashes Spanish colours. Does he know the origin of the romance? The key of D major brings ease and light into play, and the piece ends in this positive atmosphere.

Alfred-Jean-Baptiste Lemaire‘s life has been the most extraordinary of all students in Tulou’s class. He did not become a flute player, instead he was sent far away to Iran where he re-organized the military music, founded a conservatory for music, financed the Iranian pavillon at the 1889 world exhibiton in Paris and composed the first Iranian anthem. His life has been researched thoroughly by Pascal Marion whose article on Lemaire you find here. I cannot add a lot to his detailled research except Lemaire’s first biography, published on 27 July 1885 in La France. It is written in rather nationalist colours but nevertheless informative:

“Who could ever have dreamed of our military artists being promoted in the same way as a former deputy chief of the guard, now a major general in the Persian army?

Here is the curious odyssey of this character: Born in 1842 in Aire-sur-la-Lys (Nord), Lemaire (Alfred-Jean-Baptiste), entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1855, from which he graduated in 1863 as a laureate for flute and harmony.

He was deputy chief of music in the voltigeurs de la garde, when Marshal Niel, Minister of War, offered him a mission in Persia, where the Shah had set out to reorganise his military orchestras. The young sous-chef hastened to accept and left for the land of the Thousand and One Nights, where he still is.

On arriving in Tehran, Lemaire found the music of His Iranian Majesty in the most pitiful state. An Italian sailor, a fairly good cook and somewhat of a lout, had seen fit to brazenly abuse his sovereign’s harmonic incompetence to usurp the lucrative position of superintendent of fine arts. But the pot-spoon was the only instrument he ever managed to manipulate properly.

There came a time when the imperial orchestra became so cacophonous that the prince’s hard ears were themselves astonished; the Shah deftly had the European residents, who had long been bursting with laughter in their uniforms, questioned, and he soon gained a lamentable conviction.

Such was the artistic situation in Iran when Lemaire arrived there, his mind resolute and his heart throbbing with hope. One can guess that an artist fresh out of the Paris Conservatory and twice a French trooper was not long in finding his feet. In a few years of hard work and effort, M.Lemaire restored, or rather instituted from top to bottom, the musical education, he organized the imperial orchestra and he reformed all the music of the Persian army, which is now no worse than elsewhere.

The Shah, appreciating his services, showered him with favours and rades. M. Lemaire, who has lived in Teheran for seventeen years, is now a major general in charge of the superior direction of the Conservatory and the military music of the Persian Empire, in full possession of the confidence of Nasser-ed-Din, and at the head of a respectable fortune.

It should be added that he rendered innumerable and unforgettable services to the Europeans whom the hazards of life led to him through the deserts of Asia Minor. Moreover, he was a patriot in introducing the teaching of our language into the curriculum of his schools, and he thus effectively worked for the development of French influence in the East.

We must hope that one of these days he will be able to add to his titles that of legionnaire. Gambetta wanted all missionaries, religious or lay, to be supported and encouraged:

“Whatever their habit,” he said in his powerful voice, “all these valiant men are the travellers’ clerks of the Fatherland.”

Henry Thorpe was born in Landour (oriental India) on 15 August 1845. In the 19th century, Landour was a British military base, and is now owned by the Indian military. It can be assumed that Henry’s father was a member of the British military or was a missonary. So how did such a pupil end up in the Paris flute class? Since there is no information about his parents and his early life, we can only speculate. It is possible that his family had connections to France, perhaps Henry had a French mother. We have to assume that he knew the French language, as there are no reports of language difficulties. In March 1857, at the age of 12, Henry began his studies at the Paris Conservatoire. 1857 is a pivotal year for the British Army, it went down in history as the year of the Indian Rebellion. Whether the coming unrest in this year was the reason for the Thorpe family’s departure is not known. What is known is that Henry must have an exceptional talent for the flute, as Tulou speaks enthusiastically about his new pupil:

“has great musical intelligence; gives great expectations: he has made great progress in the short time he has been in my class; (…) gives me the most brilliant expectations, very good musical organisation“ (June, December 1857).

Only five months after beginning his studies, he is almost thirteen years old, Henry takes part in the concours and receives a second accessit. Tulou’s enthusiasm continued the following year:

“a lot of future; a lot of facility, a beautiful tone, extremely distinguished pupil, will, I hope, get a justly deserved first prize (1858), bright hopes (1859)”.

Despite all the high expectations, Henry wins a second prize. It was to be another three years before he would take part in a concours again. In 1859 Tulou retired and Dorus took over the flute class. It is likely that Henry is now taught on the Boehm flute. In 1861 he finally wins a first prize. The press speaks very highly of him and his new teacher Dorus.

„This class has completely recovered since M. Tulou left the Conservatoire, and the flute students have finally come out of the rut in which the other wind instrument classes are always buried. Among the seven competitors, presented by M. Dorus, we noticed especially Messrs Thorpe and Génin, who very ably performed the piece composed especially for the occasion by M. Henri Altès, M. Dorus’ colleague at the Opéra. Messrs Thorpe and Génin are the only students, of all those crowned in this session, who truly deserved their first prize.“ (La Causerie: journal des café et des spectacles, 18 August 1861).

Henry remains at the Conservatoire and enrolls in harmony. In 1865 he receives an accessit for this. By now he is 21 years old and begins to earn a living as a musician. There is little information about the following years. A concert report in the newspaper La Plage: feuille trouvillaise of 9 September 1866 praises his beautiful flute playing:

“A fantasy by Tulou on Marco Spada was brilliantly performed on the flute by Mr. Thorpe. This young artist has great qualities; his playing shines above all in rapidity, clarity and elegance. Mr. Thorpe’s success was complete.”

For the next 11 years, things went quiet around Thorpe. Presumably, in the 1870s, he enters the service of Baron Paul von Derwies (1826-1881), a heavily wealthy art-loving entrepreneur. Von Derwies plays the piano himself and builds his winter residence Valrose in Nice in the 1860s (today the neo-Gothic castle belongs to the Université Côte-d’Azur). In 1872, the Wagner fan forms an orchestra based on the Bayreuth model, initially with 35 musicians. Thorpe may have been there from the beginning.

In 1877 Thorpe plays a concert in the concert series Concerts populaires in Marseille. The newspaper L’Abeille reports on 24 November:

“Mr. Thorpe, in a very pretty pastorale for flute, was able to highlight the great qualities that distinguish him: a suave and pearly style of playing, and a certainty of passage work that is always clear and brilliant. Bravo to the artist, who was greatly applauded by the audience.”

In the following years, Thorpe could be seen in concerts of various associations, such as the Société des concerts populaires, Société des concerts classique or the Concerts de l’Association artistique. From about 1884 he plays the flute in the city orchestra (Orchestre Municipale) of Marseille. Thorpe plays solos in orchestral works such as the Arlésienne Suite by Georges Bizet or Orphée by Gluck and also appears as a soloist. His repertoire includes works by Briccialdi (Fantaisie), Boehm (Grand air varié), Demersseman (Air varié, Solo sur une mélodie de Chopin), Reicherck (Mélancholie – grand air variété), Popp (Ave Maria, Chanson de Bohème) or Damaré (Le Rossignol de l’Opéra).

Only a few concert reviews report on his playing. In most cases, the reviews are positive. On 29 January 1885, Le Mémorial des Pyrenées wrote an interesting report:

“Mr. Thorpe once more displayed and appreciated his talent on the flute. The instrument did not seem to be up to the soloist’s standard, and this is indeed regrettable; this is probably because the programme had made it a rhyme to struggle (lutte) by spelling it with two t’s. [This play on words is probably aimed at the two words lutter (to struggle) and luter (to lute). Probably Thorpe had tried to repair his flute during the concert]. In any case, Mr. Thorpe “struggled victoriously, and the applause proved it.

It is doubtful that Thorpe earned much in his life and could regularly buy a new instrument. So it was probably getting on in years and let him down in this concert.

Like his colleagues Demersseman (concours 1845) and Duvergès (concours 1856), Thorpe did not live long and died around 1887, aged 42 at the most.

The flute in this video is a flûte perfectionnée, made in Nonon’s workshop. Tulou announced his plan to perfect the flute as early as 1840 during the procès verbaux that took place to answer the question whether the Boehm flute should be taught in the Conservatoire. With this move he was able to convince the commission not to accept the Boehm flute at the Conservatoire for the time being. However, it should take ten years until the flûte perfectionnée came onto the market. Why? After the trial, Tulou was in a very comfortable situation. He won the trial. Victor Coche gave a very bad picture of himself and his model of the Boehm flute made by Buffet jeune, and Vincent Dorus, a rising star in the Paris flute world, adapted the conical Boehm flute (model 1832) to the ideal sound of Tulou. So for the time being there was no reason to continue to perfect the flute. In 1847 a new type of flute, the cylindrical Boehm flute, appeared that could become a lot more dangerous for Tulou. Unlike ten years ago, the Boehm flute in Paris followed just one standard model (in 1840 the commission criticized that there was no standard Boehm model). Tulou’s former criticism that the construction of the Boehm flute was not yet fully developed did not apply here. Furthermore, Dorus was now named in the same breath as Tulou, and if a Dorus was playing the new model, what’s to stop other flute players from doing the same? Tulou may have observed the situation for some time before stepping in and developing his own perfected flute. In 1851, he was already 65 years old, he published his “long-awaited” flute method and presented his new flute at the same time.

Jacques Nonon has been the foreman of Tulou’s workshop for more than 20 years when in 1853 he decided to leave and open his own workshop. (I recommend to read the article by René Pierre on flutes by Tulou and Nonon in his blog. He has done fabulous research on that matter!)

Nonon not only copied Tulou’s flûte perfectionnée but also tried to optimise the key system. In 1854, he submitted a patent for several improvements to the flute, and expanded it in 1855. The innovations include a double key for the low C# (it served to raise the low D), trill keys for C-D and D-E, mounted on an axle, and F and F# keys also mounted on an axle. In addition, he invented a mechanism that allowed the key and the lever to be placed on the same side. This invention was used for the long trill keys (C-D, D-E). None of the flutes known today features all the innovations. Apart from the F and F# keys mounted on an axle, none of the other inventions seem to have become established.

The flute used in this video, from the collection of René Pierre, is the only flûte perfectionnée known to date that has Nonon’s patented trill keys. For the flute player, the new mechanism does not change much, because it has no particular influence on the fingering or the tone. In terms of tone, the flûtes perfectionnées are very different from their predecessors. They have a much fuller tone, especially in the lower octave.

The opera Il Trovatore by Giuseppe Verdi was first performed in Paris at the Théâtre-Italien in December 1854. It was an immediate success and was programmed many times in the following years. Tulou chooses the aria Il balen del suo sorriso for his fantasy. In this aria (Act 2 no. 7), the Count of Luna (baritone) sings of his love for Leonora, who has entered a convent after hearing of the death of her lover Manrico.

The flashing of her smile

shines more than a star!

The radiance of her beautiful features

Gives me new courage!…

Ah! Let the love that burns inside me

speak to her in my favour!

Let the sun’s glance clear up

the tempest raging in my heart.

Tulou takes over most of the articulation and ornamentation from the original text, but changes the metronome figure given by Verdi from MM. 50 to 68 per quarter note.

Tulou dedicated the fantasy to Major Sir Warwick Hele Tonkin, a British nobleman who owned an apartment in the centre of Paris, 21, place de la Madeleine. He was one of the (vice-) presidents of the Société Universelle pour l’Encouragement des arts et de l’Industrie, founded in 1851 and based in London. Goal of the society was to „encourage the arts and industry of the entire world. The patrons of the Society are sovereigns, heads of government, and ambassadors: the title of honorary president is offered to men who have acquired just fame by their work and discoveries. The Society awards numerous prizes and encouragements, and publishes monthly in a special journal, entitled Annales de la Société universelle, reports, useful information, inventions and productions of all kinds.“ (Revue des sociétés savantes de la France et de l’étranger, Paris1854, p. 318)

In 1856, two students took part in the concours:

Jean-Baptiste-Marie (also Johannès) Donjon was born in Lyon on 5 August 1839. Both his father Alexis and his grandfather François Donjon played the flute in the local theatre. It can therefore be assumed that Johannès first learned to play the flute from them. At the age of 14, he joined Tulou’s flute class. He is a very good student, as Tulou reports: “He will become, I hope, the best pupil in my class (1855), a very distinguished pupil; an excellent pupil (1856)”. Already in the second year of his studies he takes part in the concours and receives a second prize. The following year his father died, Donjon was only 16 years old. Perhaps the death of his father was the reason why Donjon skipped the concours that year and did not take part again until a year later. In 1856, he was awarded the first prize. Tulo may not have been Donjon’s only flute teacher, as he plays together with Firmin Brossa and Taffanel Quartett with Eugène Walckiers, a popular teacher and author of a highly informative Method for the Boehm flute (1829).

After his studies, Donjon probably began to play, like many of his colleagues, in the Concerts Pasdeloup, an orchestra that engaged young laureates of the Conservatoire. On 7 April 1861, his name appeared in a concert review of the Revue Musicale. The verdict on his playing was very positive:

“M. Donjon, who, if we are not mistaken, belongs to the beautiful and pure school of Tulou (…) have above all satisfied the delicate intelligences and contributed to making us forget the insignificance, to say the least, of the rest of the vocal part.

Donjon plays in the Orchestre du Vaudeville, exactly when is impossible to say. According to Blakeman (Taffanel, Genius of the Flute, 2005) Donjon played in the Opéra Comique. I could not find any proof of this. In 1866 Donjon becomes a member of the orchestra at the Opéra. There he plays the third flute next to Ludovic Leplus and Henri Altès. In 1876, when Altès retires, he is given the post of second flute between Taffanel and Lafleurance. With the post at the Opéra, Donjon reaches the highest level an orchestral musician could reach in Paris. It is probably no coincidence that all the flute professors of the Paris Conservatoire (Wunderlich, Guillou, Tulou, Dorus, Altès and Taffanel) were principal flutists in this prestigious orchestra. The post at the Opéra is also the ticket to higher musical circles. Compared to his fellow students, Donjon plays in an exceptionally wide range of concert series. He seems to be particularly fond of chamber music. Over the years, he builds up a varied repertoire and performs with different chamber music partners. His concert repertoire includes sonatas by Handel, Kuhlau (with orchestral accompaniment!) and Walckiers, duos by Gattermann and Demersseman, trios by Berlioz, Lavignac and Adolphe Blanc, quintets by Mozart, Reicha, Rubinstein and Taffanel, and septets by Hummel, Widor and Blanc. Even before Taffanel, in the autumn of 1869, Donjon founded a Société musicale pour l’exécution de quintettes harmoniques with his colleagues Triébert (oboe), Turban (clarinet), Garigue (horn), Lalande (bassoon) and Populus (organ or piano). The first concert takes place on 2 December. We find information about the ensemble’s repertoire in an advertisement in the Ménestrel of 14 January 1872:

“The Société des quintettes harmoniques will resume its chamber music sessions on the third Saturday of each month, beginning on 20 January 1872. This Society, founded in 1869, in the Salle Gay-Lussac, rue Gay-Lussac no. 41 bis, by Messrs: Donjon, flutist; Triébert, oboist, Turban, clarinet, Garrigue, horn of the Opéra-Comique, Lalande, bassoon of the Concerts populaires, and A. Populus, maître de Chapelle, organist, has already made known, and we must congratulate him for this, in addition to the masterpieces of Beethoven, Mozart, Reicha and Weber, several works by modern composers such as A. Blanc, C. Saint-Saëns, Barthe etc. Good luck for classical music lovers who will come to the Gay-Lussac hall.”

The classics are not always well received. In 1875, Reicha’s quintet receives “a rather cold reception” (Annales du théâtre et de la musique 1876, 534). However, Donjon has particular success with an old master. In 1873 he plays a

“fragment of a superb flute sonata by Handel, masterly rendered by M. Donjon. Hearing this last work gave me the idea of doing some research on the sonata, I will give some information on this form of instrumental music, which has been neglected for many years,”,

reports the newspaper Le Soir on 20 May. Donjon will regularly perform Handel’s sonatas in concerts for many years to come. In 1880, the Revue du monde musical et dramatique ( vol. 3 138) writes:

“A session entirely devoted to instruments, even to wind instruments, took place at the Salle Pleyel, with the assistance of M. Donjon. The performance was perfect in every respect; one would have thought one was at the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire; and besides, what wonder, since the performers were Messrs Taffanel, Donjon (flutes), Gillet, Boullard (oboes), Grizez, Turban (clarinets), Garigue, Dupont (horns), Espaignet and Bourdeau (bassoons). The one and only solo was given to the flute in a Handel sonata, which M. Donjon played with the purity of sound and delicacy of style that are familiar to him; M. Diémer played the piano.”

Concerts such as these are mainly organised for a more discerning audience, and the events take place within the framework of the Société des Beaux-Arts, Société de musique Classique, Société des Concerts or Société des compositeurs. The concert events are called Enfant d’Appollon, Petit Bayreuth or Concerts du Grand-Hôtel.

However, the musicians of the Opéra do not only play music of the highest standards. They can also be found in more popular concert series such as that of the Jardin zoologique d’acclimatation, a zoo inaugurated in 1860 by the then Emperor Napoleon III and home to over 100,000 animals. The concerts take place on Thursdays and Sundays at 3pm during the concert season. Their programme is similar to those of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées, entertaining orchestral music paired with solo performances by individual musicians. Between 1872 and 1880, Donjon, like his quintet colleagues, performs regularly in this concert series, mainly with the piccolo. He composes his own works for this occasion, such as Valse or Le Zizi for one piccolo or duo, Tracoline or Rondo for two piccoli and orchestra. He also plays works by other composers, such as Le Colibri by Adolphe Sellenick or Le Rossignol by Louis-Antoine Jullien.

From 1880, when he is 41 years old, his name appears much less frequently in newspapers and he performs less often in concerts. In his place, his colleague Lafleurance, third flute at the Opéra, now regularly appears in concerts in the Jardin zoologique d’acclimatation and plays Donjon’s works for piccolo. The reason for this could be Donjon’s appointment as the first flutist at the Opéra and an associated increase in salary. From 1881 onwards, he is mentioned in concert reports as the Opéra’s first flutist. It is possible that he shared the post with Taffanel; more research would need to be done on this. Donjon also taught at the école Rocroy-Saint-Léon, as evidenced by the following article in Figaro on 7 May 1883:

“A touching ceremony brought together, yesterday, at the Rocroy-Saint-Léon school, the parents and pupils of this establishment. On the occasion of the first communion, a solemn greeting was sung in the chapel of the institution, decorated for the occasion with perfect taste and great magnificence. M. Donjon, principal flute of the Opera and teacher at the institution, lent the assistance of his remarkable talent to this family celebration, which was wonderfully successful.”

In 1890, at the age of only 51, he ended his work at the Opéra. According to several sources, he died in Paris in 1912.

Marie-Joseph Duvergès (also Duverger) was born in Auch (South of France) on 3 October 1838.The circumstances when and why he was sent to Paris are not known. Perhaps he showed talent on the flute, perhaps the family sent their son to the military school in Paris. He is already 18 years old when he enters Tulou’s class in 1855. He does not take part in solfège, nor in harmony lessons, so he must have received musical training beforehand. Tulou is pleased with him. He reports:

“ease, fairly good musician but the embouchure a little hard (21. January 1856); has made much progress, can compete this year (18. June 1856)”.

Duvergès receives a first accessit. It will be the only concours in which Duvergès takes part, as he leaves the Conservatoire the following year. Tulou tells us why:

“very good pupil; but having been obliged to take a place as a petite flute in a regiment, it is to be feared that our hopes of his future talent will not be realised”.

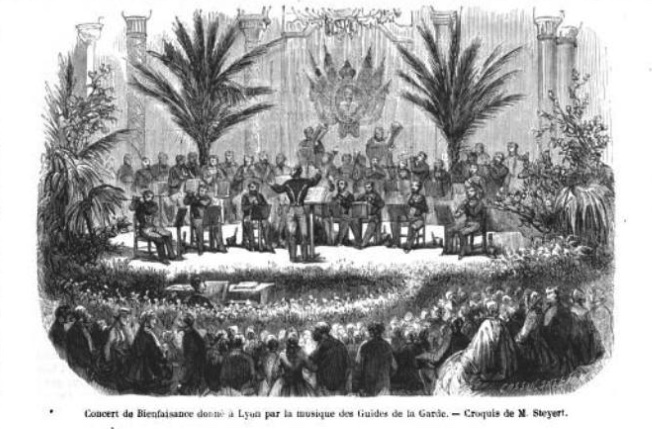

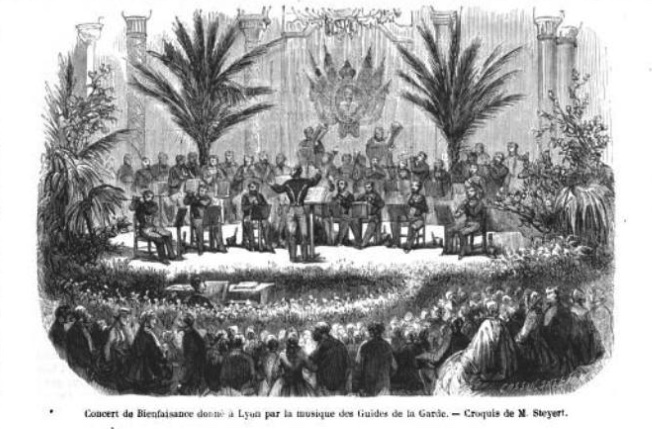

At first, the talent seems to have been lost. However, Duvergès was given the opportunity to join a special guard, the Musique des Guides de la Garde Impériale. This was founded in 1852 as the musical showpiece of the new Emperor Napoleon III. In addition to the usual brass instruments of trumpet, horn and trombone, it consists mainly of the instruments newly developed by Adolphe Sax plus some woodwinds (flute, oboe, clarinet). The harmony orchestra not only plays on official ceremonial occasions, but also performs for the people as depicted in the L’Illustration, Journal Universel (24e année, vol. XLVII, p.220).

From November 1862, various newspapers report on solo performances by Duverger. He mainly plays light music, airs variés, fantaisies duos with oboe. The opinions about the young flute player are consistently positive, if one is to believe the newspapers:

“(…) a final piece for the flute, composed by that other great artist who is called Duverger. (Feuille de Provins 22. November 1862),

“We have especially enjoyed a delicious theme on which the flute of M. Duverger makes its silver notes vibrate in the happiest way. (Journal de Seine-et-Marne, 17. November 1866).

“A new fantasy on Moïse, (for two octave flutes) (…) in which Messrs Fabre and Duverger let the delicious timbre of their instrument shine, was received with enthusiasm by part of the audience: it is the intelligent part that we want to speak of and not the one whose sole purpose seems to be to cover the voice of the soloists with the noise of intimate chatter. (…) You know Cherubini’s words: “I know nothing more boring than a flute piece, except a piece for two flutes’; The illustrious director of the Conservatoire would certainly not have made this joke if, like us, he had heard, through the melodic ideas of the theme of this Swiss air, the dazzling cackling of carried away lines, of trills beaten with precision and incomparable equality, chased in their turn with proud ardour by the scales in double tongues, which also came to seize the little instruments with an admirable power of vibration and accuracy, you would have said two imps chasing each other and making a thousand hooks and a thousand turns to avoid each other in the air. ” (Journal de Seine-et-Marne, 23. März 1867)

“A large part of the honours of the session went to Duverger and Triébert. These two virtuosos performed a duet by Gattermann, for flute and oboe, with grace, clarity, a surprising certainty of intonation, and an admirable manner of phrasing. They received the loudest applause, thanks to the lines they played with marvellous ease and agility. (Journal de Seine-et-Marne, 30. März 1867).

An attempt to bring more serious chamber music to the people achieved little success, as can be read in the Journal de Seine-et-Marne on 2 March 1867:

“One fact that we have observed in these musical sessions is the public enthusiasm that the soloists generally receive, while the ensemble pieces are, for the most part, only greeted with indifference, not to say coldness. Of course, it is not we who will protest against the applause given to virtuosos who are not afraid to face the perils of the stage in order to show off on their instrument in front of an audience of varying degrees of expertise, especially when they know how to display such brilliant qualities of style and mechanism as (…) M. Duverger did in an air varié for flute. But do you think that the instrumentalists of the orchestra do not deserve such a just appreciation and such warm admiration when they perform, as they did last Sunday. The first piece, a trio by Beethoven for clarinet, flute and oboe, called Messrs Fabre, Duverger and Triébert to the podium. Here we must, in spite of all, pause to note the superiority of ensemble and precision with which this magnificent page, though perhaps a little severe for the audience, was performed by the eminent artists we have named.“

In 1867, the Musique des Guide de la Garde Impériale was disbanded due to its high cost and insufficient usefulness in wartime situations. The musicians were either distributed among other regiments or lost their posts, as did Duvergès. Through fortunate (for him) circumstances, Duvergès immediately found another job. With Demersseman’s death in December 1866, the Champs-Elysées concert series lost one of its stars. By chance, in the spring of 1867, the Musique des Guides open the season of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées and performed every evening from 18 April to 1 May, and every Friday evening thereafter. The concerts are a great success. Duvergès plays several solos on the large and small flute during this period. In this way, the conductor of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées may have come to know and appreciate Duvergès’s playing, so that the latter is given the position of flute in the following seasons. Duvergès played in the Concerts des Champs-Elysées until at least 1871. The repertoire has changed a little since Demersseman. Instead of the regular flute solos, one now hears works with variations on different instruments or works with solos by individual instruments, as for example on 21 August 1869 (picture advertisement in the Vert-vert).

In addition to the large flute, Duvergès plays works on the piccolo (petite flûte), mostly in duets with his colleagues Fabre or Forment. Titles of these works are Le Sansonnet, Polka by G. Daniel for one piccolo or Jeanne et Jeannette – polka de Duverger, quadrille de Musard père avec variations, Polka des Fauvettes avec variations de N. Bousquet for two piccoli and orchestra. The two little flutes are very well received by the public, as the following advertisement in the Journal de Seine-et-Marne of 23 March 1867 proves:

“A new fantasy on Moïse, (for two octave flutes) (…) in which Messrs Fabre and Duverger have made the delicious timbre of their instrument shine, has been received with enthusiasm by part of the audience: it is the intelligent part that we want to speak of and not that whose sole purpose seems to be to cover the voice of the soloists with the noise of intimate chatter. (…) You know Cherubini’s words: “I know nothing more boring than a flute piece, except a piece for two flutes’; The illustrious director of the Conservatoire would certainly not have made this joke if, like us, he had heard, through the melodic ideas of the theme of this Swiss air, the dazzling cackling of carried away lines, of trills beaten with precision and incomparable equality, chased in their turn with proud ardour by the scales in double tongues, which also came to seize the little instruments with an admirable power of vibration and accuracy, you would have said two imps chasing each other and making a thousand hooks and a thousand turns to avoid each other in the air.”

Incidentally, Cherubini’s quotation is a popular catch-all for newspaper reporters to put flute players in a positive light. Duvergès was also caught once again in the newspaper La Patrie on 15 March 1870

“Let me say a few words about the new compositions of M. Duvergès, the worthy successor of Tulou, the flautist who, reversing the saying, would make the person who asked answer: “What is more attractive than a flute?-Two flutes”, of course, if Duvergès could play two at the same time, like the ancient Greeks and Romans. But don’t worry, one is enough to charm you, especially if he performs one of his latest fantasies, such as the Souvenirs de la Tourraine, or those on Crispin e la Comare and Folie à Rome. If you have heard it, there is no need for me to speak of it; if not, well, hear it; you shall speak of it!”

In 1872 Duvergès published a method for the Boehm flute. He dedicated it to the director of the Conservatoire in Lyon, Edouard Mangin, who had been founded that year. Mangin studied in Paris at the same time as Duvergès. Did Duvergès hope to obtain a post as flute teacher in Lyon with this method?

He does not seem to have succeeded, for Duvergès remains in Paris. It is not known whether he will be engaged in the following seasons of the Concerts des Champs-Elysées. From now on, concert announcements with his name become rarer. In 1872 he appeared in the 9th Festival des théâtre du Châtelet, playing his variations on Ah! Je vous dirai-je, madame on the piccolo. In 1874 he appears in an all-evening concert series at the Concerts Frascati, then disappears.

It is not known when Duvergès died, but according to Goldberg it was in 1876 or 1877, at the age of only 38 or 39. Duvergès left behind a number of works that were still published after his death. All works, with one exception, were published by Léon Escudier.

Le premier jour de bonheur: opéra comique d’Auber: airs arrangée pour flûte seule, en deux suites (1868), Crispino e la comare (le docteur Crispin), opéra-bouffe des frères Ricci, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano (1869), Une folie à Rome. Opéra bouffe de Fred. Ricci. Fantaisie pour la flûte avec accompagnement de piano (1870), 4 Fantaisies pour flûte avec acc. de piano, Verdi (1872), Ah! je vous dirais-je Maman, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 25 (1872/73), Souvenir de Touraine, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 26 (1872), Au clair de la lune L. Escudier op. 27 (1872), Aida, opéra de Verdi fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 28 (1872), Bébé-polka pour le piano (1873), New and complete method or school for the cylindrical flute english translation by E. Salabert ( 1875), Nouvelle méthode complète de flûte Boehm cylindriue (1873), Le Roi l’a dit, opéra-comique de L. Delibes, fantaisie pour la flûte avec acc. de piano op. 30 (1873), Messe de Requiem de G. Verdi, pensée réligieuse pour flûte avec acc. de piano ou d’orgue-harmonium (1874), L’Hirondelle. Polka pour petite flûte Musique militaire (1877, ed. P. Goumas).

The twelve-keyed flute in this video is completely atypical of French instruments of the time. It has, for example, a metal-lined headjoint made of ivory, many keys and tone holes with metal decorations. Although it bears the French stamp “Truchot & Cie / Paris”, it was not made in France but imported from either Austria or Italy and sold by a dealer named Truchot & Cie in Paris. I found no traces of that shop in historical sources. A Maison Truchot in Paris made and restored felt of hammers for pianos but did not advertise for selling instruments.

The sound and playing style of the flute are of course atypical for France and follow the ideal of its place of manufacture. The tone holes are on slightly different positions, the left thumb has to be put left of the Bb-key, some notes sound better with ‘German’ fingerings (such as C”’ XOX/XOX/o instead of OXO/XXX/o), and the sound is very different. I wonder who bought that instrument at that time in Paris. Given the signs of wear that person must have played the flute very much. It’s indeed a wonderful instrument, just not French at all despite its stamp.

The piano is 1843 Pleyel.

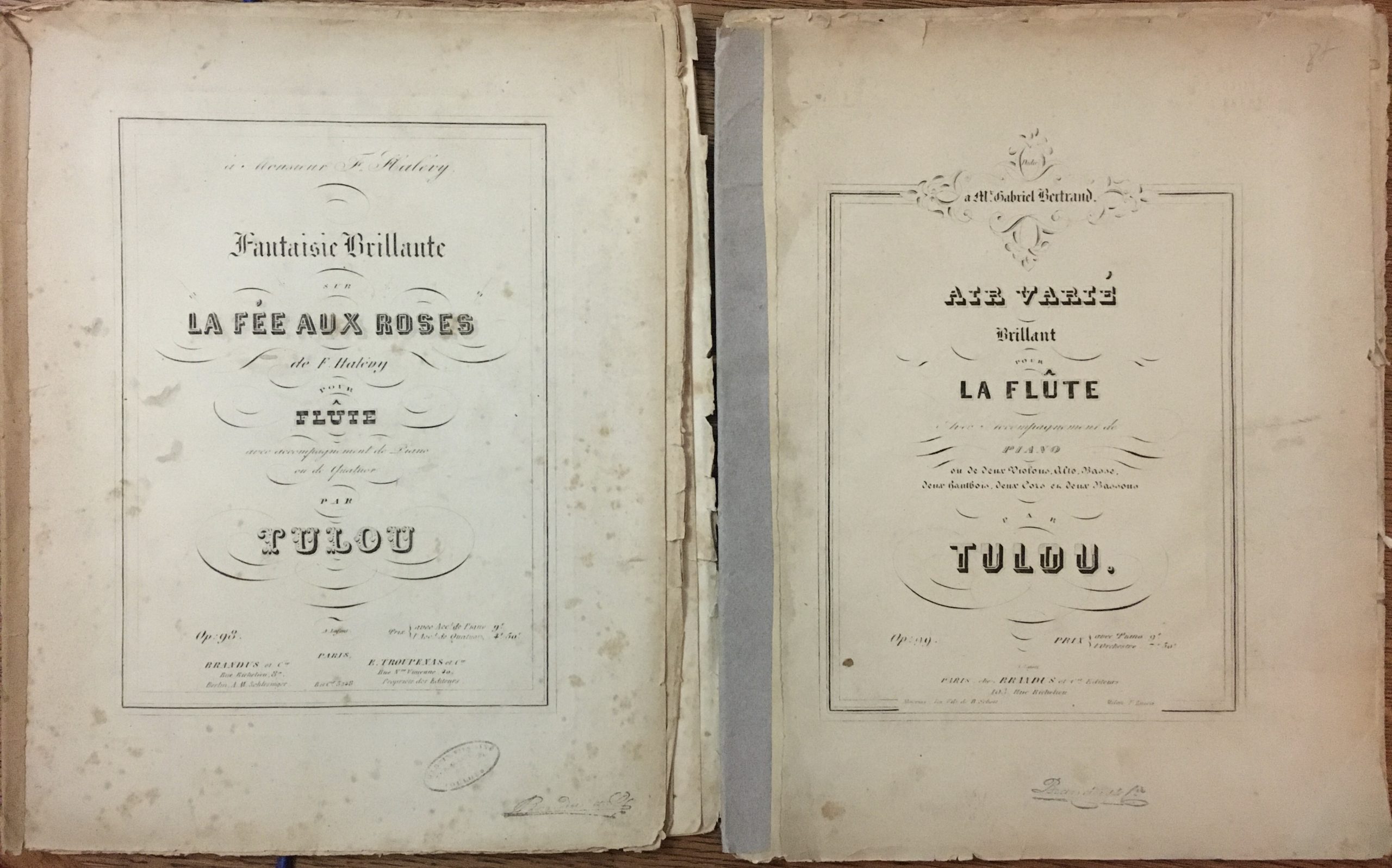

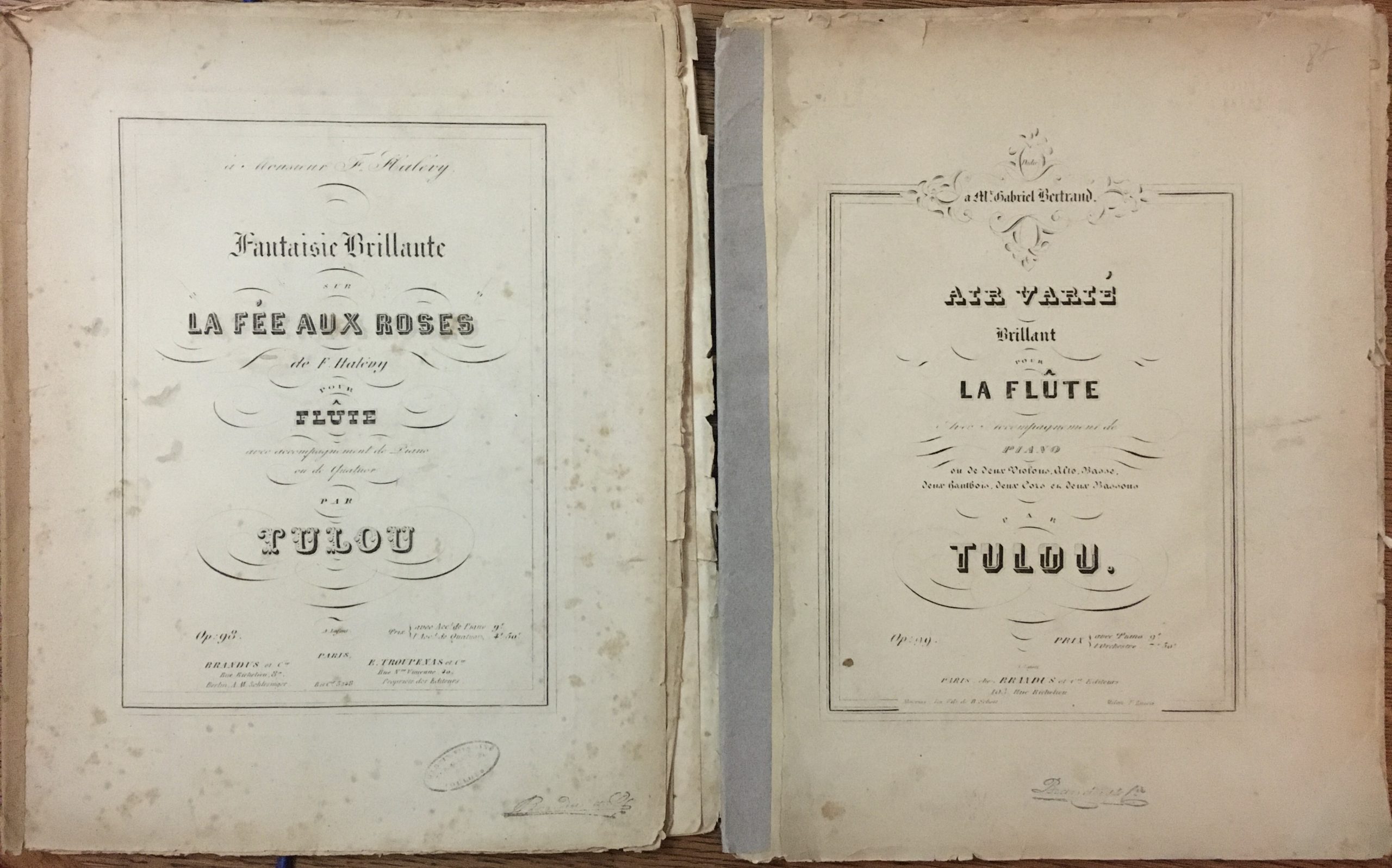

In 1851, Tulou departs from his usual tradition of composing a Grand Solo. Instead, he gives his students the Air varié brillant op. 99. The same piece is also known as op. 98. The publisher Brandus probably made a mistake in the first printing, which was passed on to other publishers (e.g. Schott) who also published the work. In 1849, Brandus had already printed an op. 98 by Tulou: Variations brillants sur La Fee aux Roses, an opera by Fromental Halevy, which was on the programme at the Opéra Comique in the same year. Brandus corrected the opus number to 99 in a second edition of the Air varié.

The Air varié is a pretty piece with a simple melody that can be varied with ease. Tulou writes three variations with an Andante sostenuto in the middle and a virtuoso ending. As in many of his concours works, he gives his students some challenging passages. The third variation in particular, with its high trills, is quite something.

In 1851, five candidates take part in the concours, three of them win a prize.

Vincent-Benoit Doudiès was born in Toulon on 30 May 1830. In 1848 he appears in Tulou’s reports for the first time who describes him as a good student: „made some progress (1848), has ease – makes progress; second prize (1849), has made significant progress, but I believe that his musical organization does not allow him to go further; worker, made progress (1850), good musician – has ease – made significant progress (1851)“ In 1849 Doudiès wins a second price, two years later he finishes his studies with a first price. After his studies he stays a little while in Paris. He is member of the Association des artistes musiciens and plays in concerts here and there. In 1854 settles in Nantes where he gets appointed first flute at the Grand-Théâtre. He does not only fulfill his orchestra duties but organizes concerts, plays flute in a military band and conducts an amateur orchestra. As soloist he plays music by his colleagues (fantasies sur La dernière pensée, La Muette de Portici, a Grand Solo by Tulou, the fantaisie sur Robert le Diable by Walckiers, Souvenir de Paganini by Cottignies a.o.) as well as his own arrangements and compositions (Fantaisie pastorale concertantes, Réveil du Rossignol, fantaisie sur La Traviata, Le cor des Alpes, Une chanson dans le Bois for voice and flute, Romance and Malborough air varié for piccolo with accompaniment of harmony band). I did not find any of these compositions nor did I find any information about whether his works were published.

Doudiès’ compositional ambitions were not restricted to flute music. He also composed at least three operettas. Croix de Pierre was performed in Nantes in 1860 and Fleur de Genêt in 1862. The ouverture of another opera Wadah was performed in Nantes in 1862 by a military band, conducted by Doudiès. The operettas did not have the succes Doudiès might have wished. In his book Le théâtre à Nantes depuis ses origines Ètienne Destranges writes in 1893 „Croix de Pierre (…) This work proved that in M. Doudiès the composer was far from equaling the flute player” (p.328) and “Fleur de Genêt (…) operetta by M. Doudiès, whose first failure had not discouraged him“ (p.338). None of these works have been published.

In the 1860s he is appointed flute teacher at the conservatory in Nantes. He holds this post until after 1890.

Only little is written about his playing. On July 22 1861 a critic writes in the Nantes newspaper La Phare de la Loire “He draws very pure tones from his flute and makes steady progress. Two solos of his composition made it possible to appreciate the sureness of a playing that the study strengthens unceasingly. His concert piece entitled Réveil du rossignol is full of difficulties which he overcomes with great happiness and accuracy.”

Auguste-Dies-Charles Brivady was born in Perpignan on 29 November 1830. He joins the flute class at the age of 17. Brivady is not a very good student and seems to loose his motivation by the end of his studies. Tulou reports: „made significant progress; has made significant progress on the flute but is still a poor reader (1848), has only recently joined my class. I am satisfied with his attitude and I hope to have a good student; has made progress – is not a good musician and reads with difficulty; second prize, made progress on his instrument but still remained a poor reader (1849), could have made much more progress if he had not been lazy; progress is insensitive, very inaccurate to class; poor organization, made very little progress (1850).“ He does, however finish his studies after four years. There is only little information about his further career. A necrology in Le Ménestrel of 10 April 1904 gives us a few hints:

“From Geneva they announced the death of a French artist who had been very distinguished for many years, established in this city, Charles Brivady, who had made a brilliant position there. Auguste-Dies-Charles Brivady, born in Perpignan on November 29, 1830, had been admitted to the Conservatory in the class of Tulou and had obtained the second prize for flute in 1849 and the first in 1851. After having belonged for some time to the orchestra of the Porte Saint-Martin theatre, he had gone to settle in Geneva, which he never left. A very brilliant virtuoso, he was a member of the theater orchestra and of subscription concerts for a long time, then became a professor at the Conservatoire, where he trained many (une pléiade) of excellent students.“

Eugène-Jean Devalois, born on 10 June 1826 in Paris, was 27 years old when he won the first price at the 1853 concours. He is the oldest documented student of Tulou’s class who finished their studies. His studies have not been without problems. He was already 19 years old when he began his studies at the Conservatoire. Tulou did not take him into his class quite voluntarily as we can read in his report from 2 December 1845. He notes: „is too old to give any hope, and above all is too little of a musician. I have kept him in the class only to satisfy the desire of the Director [Auber] and to be agreeable to the [Louis-Auguste-Michel Félicité Le Tellier?] Marquis de Louvois.“

The Marquis de Louvois was no stranger to the art world (he died in 1844, so it is strange that Tulou still felt obliged to him, or was this obligation to his nephew?). He organised concerts in his house and was a member of the “commission spéciale des théâtres royeaux” as well as of the committee of the “association des artistes-musiciens”, an association that supported poor musicians. Auber was also a member of the committee, Tulou was one of the vice-directors. Moreover, he was a loyal royalist, so it probably seemed impossible to refuse such a request.

Tulou’s concerns did not change significantly over the years, as the following reports show: „low in all; bad musician. Fair sound quality; but very difficult fingers (1846), bad musician – heavy fingers, no facility in execution – little hope (1847), little progress despite his zeal to work, goes to great lengths, without result (1848), poor musician and not very good at playing the flute, still the same – weak, his progress is still slow despite his good will (1849), despite his efforts, his progress is not very noticeable, its progress is not very significant (1850), he is a student who follows the lessons of the Conservatory with accuracy. He works hard, but his progress is slow. (1851)“

In summer 1851 Devalois finally won a second price. This seems to have given him a boost, because the following year Tulou noted: „Zealous student; has made some progress this year (1852)“ In 1853, the time had finally come and Devalois was allowed to take part in the concours. Tulou wrote in the report: „follows my class with zeal – makes good progress“, but later also „zealous student; but his progress is not very noticeable (1853)“. Against all odds, Devalois received a first prize. He fought his way through and completed his studies, not everyone succeeded in this.

His career after graduation is hardly documented. Devalois no longer appears in the press. According to Constant Pierre he later played in the Orchestre du Théâtre Lyrique.

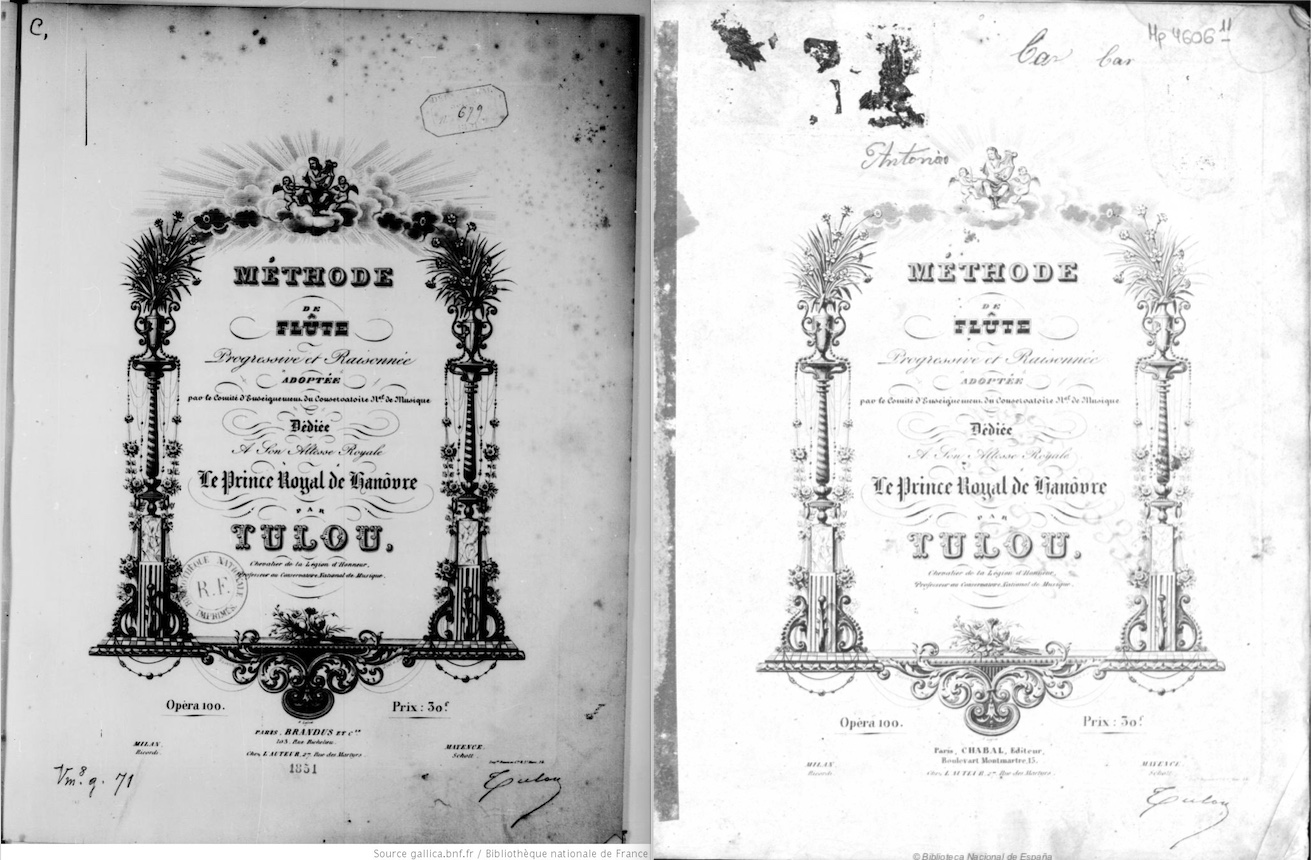

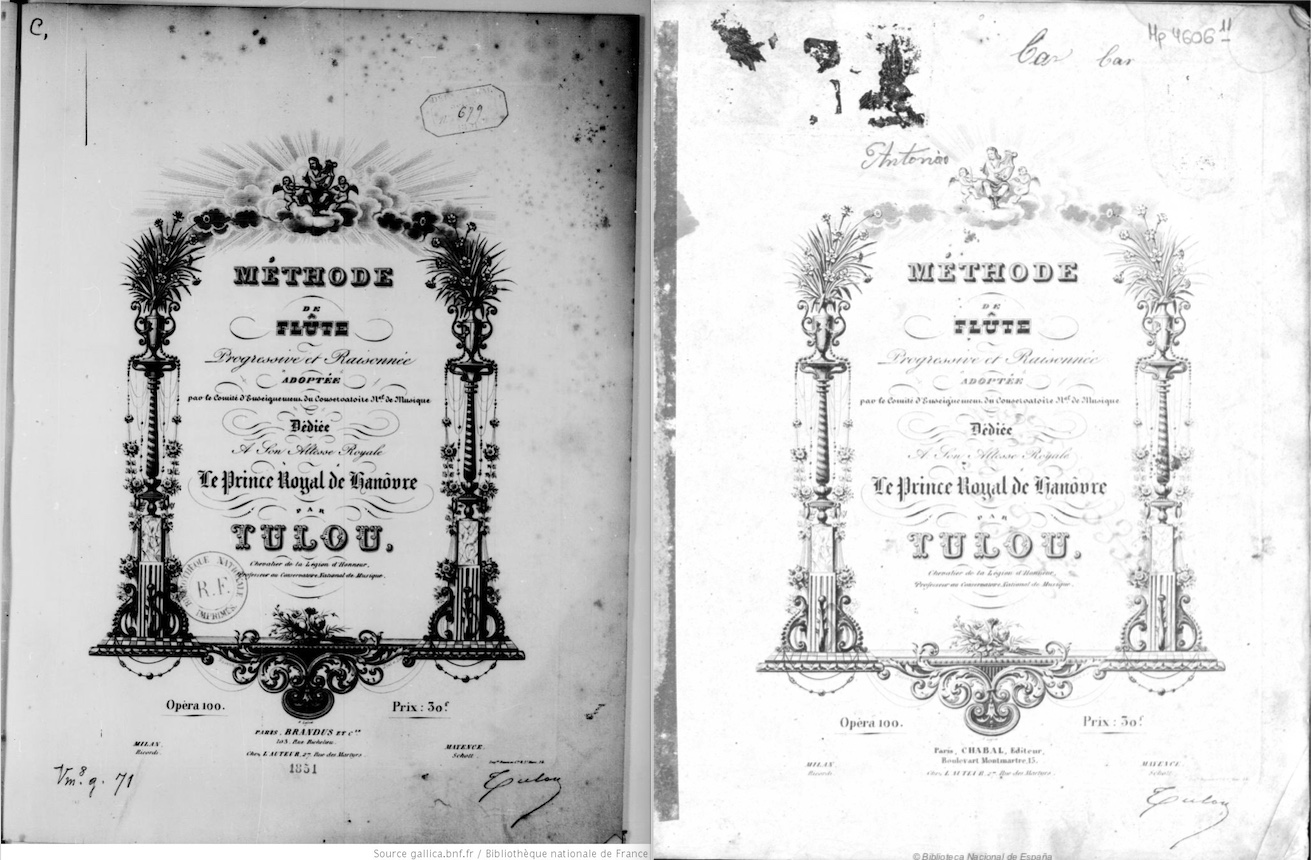

1851 is a special year for Tulou in many respects. In the summer, he publishes his long-awaited flute method op. 100. There is still much conjecture about the correct year of origin of the method, but in fact there is no longer any doubt that it is 1851. The method was published by at least three publishers: Chabal, Brandus & Cie and Schott (with a German translation). The Chabal and Brandus & Cie editions differ slightly from each other. The content is the same, but four pages with scales have different page numbers. In her dissertation about Tulou Michelle Tellier quotes a letter from Tulou to the engraver Benoit dated Sunday 4 May (the year is not mentioned, but in 1851 4 May was a Sunday) that two plates with trill charts still had to be engraved (these two trill charts are missing in the Brandus & Cie edition in National library in Paris (bnf). Benoit is the engraver of the method, he is mentioned on the front page below.

The Chabal edition could be purchased at “Editeur, Boulevard Montmarte, 15th” or “Chez L’AUTEUR, 27th Rue des Martyres”, where Tulou lived. Chabel moved to this address in 1849. Brandus&Cie moved to 103 rue Richelieu in 1851, the address on the Tulou method of their edition. So the publication date cannot be before 1851.

The method is clearly Tulou’s first one. In November 1850 Tulou wrote to the publisher Ricordi in Milan that he has been working on his method for the past 20 years, thus from 1830, his beginnings at the Conservatoire. He asked Ricordi to publish an Italian translation of his method. (I transcribed the four surviving letters by Tulou, you find them here.

There are two documents which could make us believe that there is another earlier method by Tulou:

An advertisement in the Revue musicale from 19 January 1834 mentions a “Devienne et Tulou – methode de flûte“ for the price of 18fl, a publisher is not added. A year later the publisher Aulagnier published a Devienne method with revisions of Ludovic Leplus and additional works by Kuhlau en Tulou. Does the Revue musicale refer to a Devienne method with added works by Tulou? Aulagnier must have published another Devienne method before 1828 as it is mentioned in a catalog by Whistling (Handbuch der musikalischen Literatur). It might be the same.

The second document is a letter from the administration of the Paris conservatoire to the administration of the Lille conservatoire from 12 November 1845 the writer gives a list of methods used for the education at the Paris conservatoire (cited in Giannini, Great Flute makers of France). The administration mentioned indeed a Tulou method, however, they also mentioned a trumpet method by Dauverné which has not been published before 1857. Was the Tulou method an unpublished document or the first version of his flute method? And if another method existed, why didn’t he mention it in his letter to Ricordi?

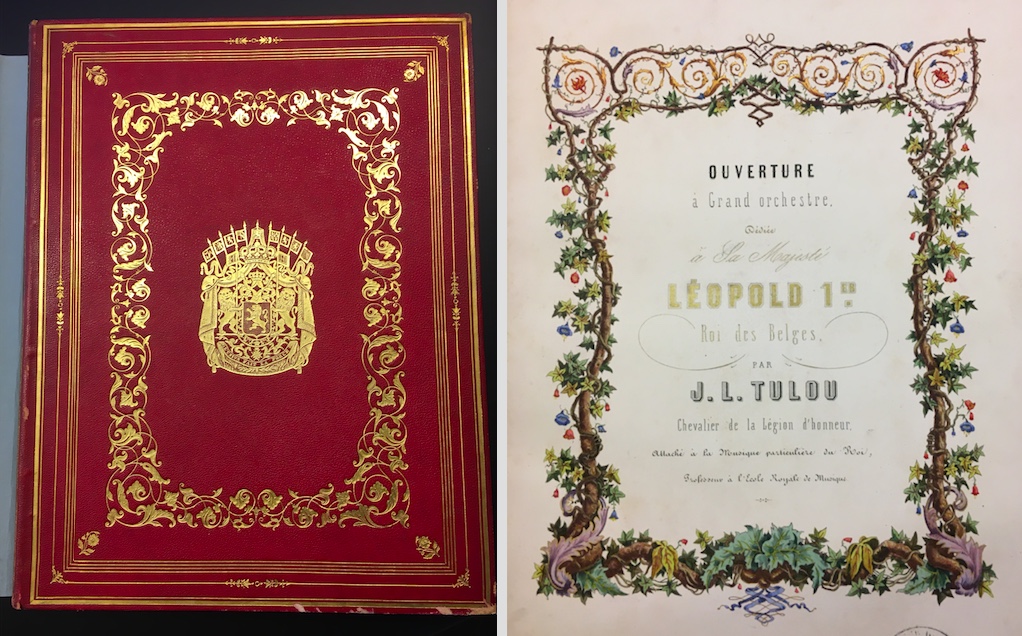

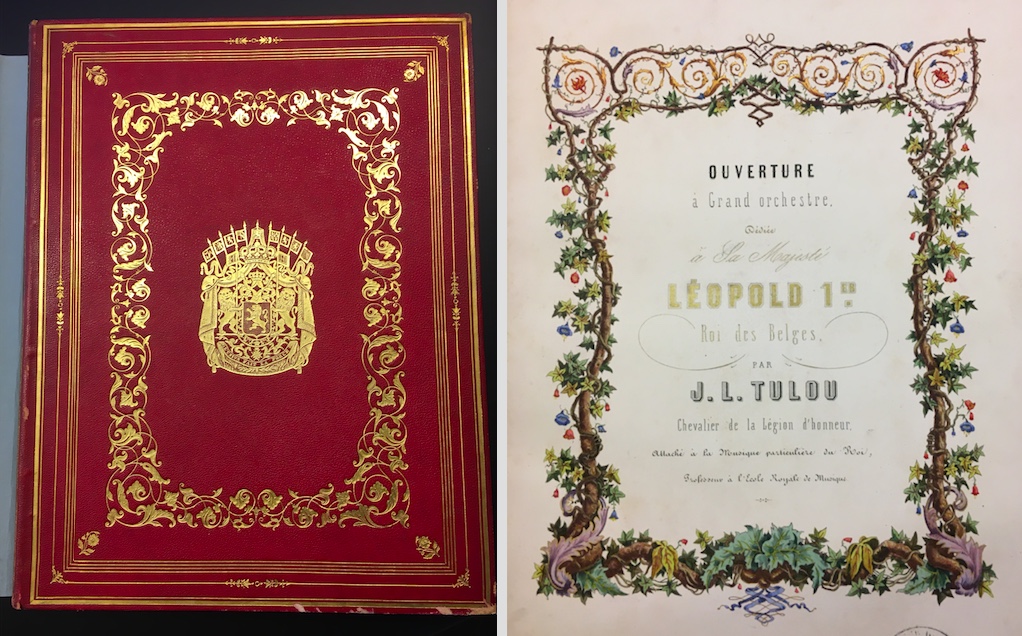

In October 1851, Tulou was honoured to receive a medal from the Belgian King Léopold I. He was now allowed to call himself Chevalier de l’Ordre de Leopold. For this occasion, Tulou composed what is probably the only orchestral work in his oeuvre, the Ouverture à Grand orchestre for harmony orchestra. He presented the beautifully designed manuscript, now in the library of the Royal Conservatoire in Ghent, to the King of Belgium.

The flute in this video is a flûte perfectionnée, made in Nonon’s workshop. Tulou announced his plan to perfect the flute as early as 1840 during the procès verbaux that took place to answer the question whether the Boehm flute should be taught in the Conservatoire. With this move he was able to convince the commission not to accept the Boehm flute at the Conservatoire for the time being. However, it should take ten years until the flûte perfectionnée came onto the market. Why? After the trial, Tulou was in a very comfortable situation. He won the trial. Victor Coche gave a very bad picture of himself and his model of the Boehm flute made by Buffet jeune, and Vincent Dorus, a rising star in the Paris flute world, adapted the conical Boehm flute (model 1832) to the ideal sound of Tulou. So for the time being there was no reason to continue to perfect the flute. In 1847 a new type of flute, the cylindrical Boehm flute, appeared that could become a lot more dangerous for Tulou. Unlike ten years ago, the Boehm flute in Paris followed just one standard model (in 1840 the commission criticized that there was no standard Boehm model). Tulou’s former criticism that the construction of the Boehm flute was not yet fully developed did not apply here. Furthermore, Dorus was now named in the same breath as Tulou, and if a Dorus was playing the new model, what’s to stop other flute players from doing the same? Tulou may have observed the situation for some time before stepping in and developing his own perfected flute. In 1851, he was already 65 years old, he published his “long-awaited” flute method and presented his new flute at the same time.

In 1856, Tulou reported in an article in the Revue musicale that the acoustics of the flute were completely recalculated and the bore and tone holes were adjusted. In the process, however, it did not lose the flute’s original sweet tone. Compared to the cylindrical Boehm flute, the tone is indeed more mellifluous. Nevertheless, his flûtes perfectionnées have a more powerful tone than their predecessors.

Jacques Nonon has been the foreman of Tulou’s workshop for more than 20 years when in 1853 he decides to leave and open his own workshop. (I recommend to read the article by René Pierre on flutes by Tulou and Nonon in his blog. He has done fabulous research on that matter!) At the moment it is impossible to put a year on the flute I play in the video. It could have been made before 1854. However, there are similar flutes that can be dated much later. Its key system differs slightly from Tulou’s flutes but does not have all improvements that Nonon patented in 1854. The stamp does not bear the patent mark (brevet). Here, he places the F#, short F- and low D#-keys on rods. The Bb- and short C-key are separate.