1860 – Tulou, 5e Concerto (excerpts), op. 5

Tulou’s 5me Concerto op. 37 was published in Paris by Pleyel et fils ainé in 1824 and in Bonn by Simrock in 1825. Dorus played fragments of the concerto on 28 January 1844 at the second of the concerts of the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire held in winter and spring (“Histoire de la Société des concerts du Conservatoire impérial de musique” A.-A.-E. Elwart 1860, p. 216). The music critic Joseph d’Ortigue was in the audience and published a concert review in the France Musicale on 2 February. Here it states:

“A large part of the honours of the session went to M. Dorus. This virtuoso performed with grace, neatness, a surprising certainty of intonation, and an admirable manner of phrasing, two parts of M. Tulou’s fifth concerto for the flute. This concerto, tastefully composed, finely and soberly instrumented, and in a style perfectly suited to the instrument, is full of delightful things. The rondo is reminiscent of Weber’s concerto for piano and orchestra; I would only like to see the B minor reprise disappear, although M. Dorus received the most lively applause, thanks to a passage that he played with marvellous ease and agility. M. Tulou must be proud to have made such a student. It is certainly one of his most beautiful tones of glory. Not only does M. Tulou continue in M. Dorus, but he progresses in him; nevertheless the master and the pupil, or rather the two masters, each have their own style and individuality; and that is why it is easier to make comparisons than to determine a preference.“

Dorus, a lifelong admirer of Tulou’s flute playing, may have seen the concerto as a good start in his teacher’s footsteps and chose it as his first concours work. It would not be the only work of Tulou’s that his students would play in the concours. In the course of his eight years of teaching, he also chose the 3me and 13me Grand Solo as well as fragments of the 4me concerto, the first movement of which he himself played in a Société concert in 1845.

Tulou had not planned a piano reduction of the orchestral accompaniment for an edition. Fortunately, however, another flute player took over this work. Christian Gottlieb Belcke (1796-1875), flute player of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra from 1818 to 1832 and travelling flute virtuoso, played Tulou’s flute concerto in various concerts. The Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung reports one of these concerts on 8 March 1826:

“A new flute concerto by Tulou was performed by Mr. Belcke with his usual skilfulness. The composition was quite good.”

The rather subdued opinion of the quality of the concerto is probably due in large part to its sprawling length. Tulou’s concertos were not the only ones to be subjected to this criticism. Probably for this reason, Belcke edited the concerto and later performed it in an abridged version. A review dated 16 February 1831 states:

“Mr. C. Belcke had arranged a flute concerto by Tulou, which was too long for our time, with deft insight into a concertino, which he performed splendidly and earned deserved applause for it.”

The success of his arrangement may have prompted him to publish this version. Belcke added a piano accompaniment to the abridged concerto, and in 1832 it was published under the title Concertino pour Flûte avec accompagnement de Pianoforte, arrangé d’après le 5me Concerto par C.G. Belcke. The target audience for this edition were good amateurs, as evidenced by the following article in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung of January 1833:

“The widely known and often favourably received fifth concerto of the celebrated flautist has been tastefully arranged here by a recent virtuoso of the flute, who has also already made himself sufficiently known as a composer, for skilful lovers of the flute and provided with light pianoforte accompaniment, so that it will provide an evening’s entertainment in domestic circles that is not too difficult, but nevertheless very brilliant and requires good skill, for which we highly recommend the work to all friends of this kind of music.”

Belcke shortened the concerto by about a quarter. He deleted many passages, including the second theme of the first and third movements. He changed the articulation in some passages, and added ornaments and transitions between the movements. Since he played a German flute with a B-foot, he also used these low tones. For the recording, we used Belcke’s piano reduction as a basis, but as far as possible, I used the original flute part with the original articulation.

“Nota: La plupart de ces élèves, ayant changé d’instrument et la Classe étant très nombreuse, ont besoin de beaucoup d’indulgence. L. Dorus” (Note: Most of these students, having changed instruments and the Class being very large, need a lot of indulgence. L. Dorus) Archive Nationale de la France AJ/37/277, 15

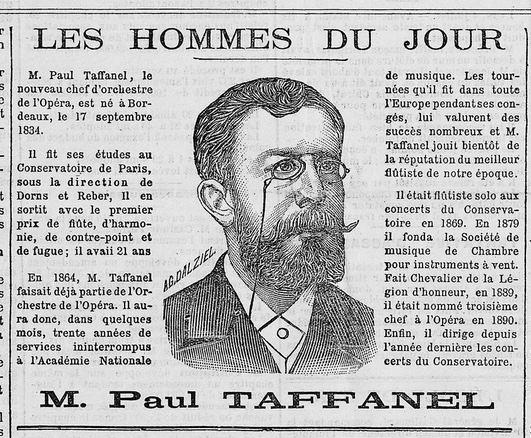

Claude-Paul Taffanel, born on 16 September 1844 in Bordeaux, is still a familiar name to most flute players today. In his wonderful book, Taffanel Genius of the Flute, Edward Blakeman has already described in detail the life of this eminent flute player, pedagogue and conductor, so I will be brief here and just add a few thoughts.

Taffanel’s flute-playing qualities are undeniable. He is invariably described as an outstanding and sensitive musician who knows how to sing on the flute. According to Blakeman, he changed the traditionally virtuoso flute style of his predecessors Dorus, Altès and Tulou to a singing and substantial playing, which is also reflected in his compositions (in contrast to the works of his predecessors). For all the enthusiasm about the great Taffanel, Blakeman’s book seems to insist that his predecessors’ style was mainly virtuosity (pp. 12, 14, 26, 57). Here I must disagree with him. Virtuoso playing was only partly the focus, especially in the open-air concerts attended by the common people. A comparison of concert reviews of the great flute players Tulou, Dorus and Taffanel shows how much the demands on the them were similar. Here is an example of several reviews. The reader is invited to match the descriptions to the respective flute players. You will find the solution at the end of this article.

1 „It is impossible to hear a more beautiful tone than Mr. *** is able to elicit from his instrument. Since I heard him, it no longer seems so inappropriate when our poets compare the melodiousness of a beautiful voice to the tone of the flute.“

2 „The success of this young virtuoso also left nothing to be desired. Next to such an instrumentalist, the task of the singers becomes greater, and one must be called Marie *** and Jules *** to shine after (he played).“

3 „If it is possible to perform more tours de force on the flute than ***‘s playing offers, it is not possible to sing with more charm, to give more grace to the difficulties, to modify the tone with more expression, in a word, to be a more perfect flautist (…) (he) is the first to have realised that simple singing, performed without any other ornaments than the inflections of the tone, was a powerful means of effect.“

4 „The human voice does not sing better than the flute of Mr. ***“

5 „The instrumentalist had just given the singer the best lesson she could have received.“

6 „Chromatic scales, arpeggios, double tongue strokes, organ point as far as the eye can see, all this is played by this artist with such ease and comfort that one would be tempted to believe that there is nothing but simplicity here, if experience did not prove the contrary. (…) His playing is pure, his style elegant. He phrases without pretension, and sings with impeccable accuracy and taste.“

7 „(…) perfect equality between the low and high register“

8 „(He) possesses a made talent; he plays, with an ease full of grace, all the difficulties of mechanism. He sings very well, and his tones, always in perfect tune (which is rarer than one might think on the flute), are remarkable for their fullness and purity.“

9 „Then Mr. *** with his flute, so soft, so flexible, so pure; the piece he performed is a small masterpiece of simplicity and good taste.“

10 „This artist plays the lines with a lightness, sharpness and rapidity that are truly miraculous.“

All three flute players have one quality in common: it is the ability to make the instrument a voice and equal singers. They have reached the ideal of flute playing, be it in lyrical or virtuoso works. Taffanel was no exception in this respect. To accuse the predecessors of empty virtuosity does them an injustice, in my opinion.

Paul-Agricole Genin born on 14 October 1832 in Avignon, is already relatively old when he enters the Conservatoire in 1860 at the age of 27. He was already earning his living by playing the flute, among other things by participating in the Concerts Musard, which took place several times a week during the summer season. Genin plays alongside Jules Demersseman in the orchestra and also shows himself soloistically, mostly in an air varié. A first prize at the Conservatoire would significantly increase his value as an artist. It seems as if he had been waiting for the moment when Dorus would take over the post of flute teacher. Perhaps he was already his private pupil, perhaps he wanted to switch to the Boehm flute. Dorus is very pleased with his pupil and reports in the reports:

“has made much progress in style and quality of sound, very good student in all respects, can compete, has made much progress, has perfect knowledge of the mechanism of his instrument (1860), very good, excellent musician (1861)“

In 1860, Genin won a second accessit, followed by a first prize the following year. In addition to his studies, he continued to perform in the Concerts Musard. From 1862 the concert series is called Concerts des Champs-Elysées. In 1863 he was appointed principal flutist at the Théâtre Italien, which only performed during the winter season. In the summer season he continues to play at the Concerts des Champs-Elysées. The repertoire is limited to lighter music such as overtures, polkas, waltzes, quadrilles, marches with and without soloists. Like Demersseman, Genin also composes pieces for these concerts. Since the concerts take place outdoors, the piccolo is particularly suitable for this. Genin composed Il pleut, il pleut, bergère fantaisie pastorale pour petite flûte, Air varié sur un thême espagnol pour petite flûte, Polka des Fauvette (for two piccoli and orchestra), Fantaisie sur La Fille du régiment, Malborough or Fantaisie sur un air de Crispino e la Comare, among others. In 1864, the public could even enjoy a quadrille, Les Echos, for four piccoli, played by Demersseman, Gobin, Soler and Genin. In 1867 follows L’Angleterre, quadrille also for four piccoli, this time played by Génin, Duverger, Damaré and Muller. 1867 is the last year in which Genin takes part in the Concerts des Champs-Elysées. After that, only his works, played by other flute players, can be found in the programme of this concert series. In the summer of 1869, Genin plays in the concerts of the Casino in Vichy. After that, his name appears less frequently in the newspapers. According to Constant Pierre, Genin is also a flute player at the Comédie–Française and plays in the Concerts du Châtelet, of which I have been unable to find any evidence. From 1873 he appears in a concert with the Spanish singer Marina Albini, who has been employed at the Théâtre Italien since 1854. Together they present the Mad scene from Lucia di Lammermoor by Donizetti on 30 March in the salon of Baron and Baroness Rothschild and on 15 March 1875 in the Salle Duprez. The opera is part of the programme at the Théâtre Italien during this period. In 1877, the role of Lucia was recast with the American singer Laura Harris. As a newspaper article of 22 April 1877 describes, she sang her role in a different way:

„Mrs. Harris has a most extensive and flexible voice; she dares to make very successful aerial staccati. Nature has done everything for her; art and taste sometimes betray her (…) There are in her voice, in her talent, surpises which accuse the American style, but whose happy boldness disarms all criticism. Mrs. Harris does not leave you time to meditate on her phrasing. She led Lucia on an express train and was able to get to the madness act well ahead of time, where Mr. Génin’s flute had some difficulty in keeping up. What followed Ms. Harris all evening was the audience’s bravos.“

In 1880, together with his colleague Auguste Joseph Cantié and Adelina Patti, Genin plays the trio C’est bien l’air from Meyerbeer’s opera L’Etoile du Nord, which premieres on 16 February at the Opéra-Comique. It’s finale consists of a great trio for two flutes and voice in which all three parts play an important role as you can see in the short excerpt below.

In 1883 Genin took part in a concert in the dinner concert series of the Grand Hôtel, then his trail disappears. According to Goldberg, Genin died in 1903 at the age of 71.

Genin’s oeuvre is quite impressive. He composed mainly light light music. In 1872, he composed a one-act opéra comique, Saint Patrick, together with Bassen.

The newspapers provide little information about his flute playing. An article in the newspaper La Comédie of 9 July 1865 reports on his performance in a concert in Reims:

“M. Génin, soloist of the Italians, is an artist in the broadest sense of the word: the sweet melody of the instrument that used to be a reed blossomed deliciously under the silver-lit canopy; the caressing notes of the flute sheltered lovingly under the tree branch quivering with the evening kiss and still whispered to attentive ears.

The newspaper La Patrie wrote about his piccolo playing on 12 September 1865:

“M. Génin, who makes his little instrument babble, a djinn flute, the flute of Trilby or Queen Mab, which sometimes chirps like a warbler, sometimes throws its rocket of bright notes into the air, sometimes finally seems to imitate the pearl-like laughter of a young girl.”

Hildephonse-Henry Hitzemann born on 14 August 1842 in Bailleul (Nord), appears only once in the teachers‘ reports of the flute class. He is probably one of the military students. In 1860 he got a first accessit and left the Conservatoire. He became sous-chef de musique in 1865, chef de musique of the 94th infanterie on 22 May 1873 and changed to the 106th infanterie.

Edmond Sténosse, born on 7 April 1839 in Auxonne (Côte-d‘Or), is one of the students who spend only a short time at the Conservatoire. He begins studying with Dorus in 1860, like six of his fellow students, although he does not even have a suitable flute, as Dorus reports:

“doesn’t have an instrument yet, he is obliged to work with a fellow student’s flute, in spite of this, he has made progress, he will have a good embouchure.”

Just two months later, Sténosse takes part in the concours and receives a second Accessit. It was to be his only prize at the Conservatoire. Sténosse stayed another year and then leaves the class. It is not until many years later that there is any trace of him again. In 1873, by now 34 years old, he performs in the concert series of the Jardin Zoologique d’Acclimatation. The orchestra plays light entertainment music on Thursdays and Sundays at 3 pm. The summer of 1873 would be the only season in which Sténosse would perform in this orchestra. In the years that follows, he finds various jobs in the summer months outside Paris. It is striking that he plays in a different place almost every summer. Whether this is his choice or whether he is merely following work, we do not know. Sténosse plays mainly in seaside bathing centres, at the Casino des Bains du Mail (1874, 1876), at the Sociéte d’artistes in Tréport (1877), at the Casino d’Arcachon (1880), at Jules Strauss’s orchestra in Caen (1883), and at the Casino in Dieppe (1887). Sténosse seldom performs solo works, but there is evidence of Le Sannsonnet, a polka for piccolo and orchestra by A. Douard, and solos by Demersseman. In 1875 he plays a Sérénade pour quintette harmonique by Barthe in the Cirque Fernando, and in a quartet concert on 13 February 1876 in the Salle du cercle du boulevard, he plays Weber’s Trio op. 63, Gluck’s Entracte in an arrangement for flute and string trio, and Beethoven’s Serenade.

Sténosse’s playing is rarely reported. Only two reports of concerts outside Paris are known to me:

“M. Sténosse played with his usual talent a very pretty flute solo by Demersseman, on motifs from the Juive. The more one hears this artist, the more one is delighted by the purity and beauty of his tones! As well as his prodigious fingering agility, a little more feeling in the singing and it would be perfect. (2. September 1874 L’echo rochelais)

“It would be unfair not to give a special mention to the soloists, who are masters, and in particular to M. Sténosse who obtains from his instrument a truly phenomenal purity of sound, and who is certainly one of the most skilful flautists we have ever heard.“ (Le Monde artiste 28. July 1877)

During the winter months, Stenosse returns regularly to Paris, where he performs here and there, such as at the Cirque Fernando (1875) and the Orchestre des Bouffes-Parisiens (1876). Around 1878 he is finally offered the post of third flute player at the Opéra-Comique, alongside Brunot and Lefèvre. However, as the orchestra is only active during the winter season, the musicians have to look for other playing opportunities during the summer months.

In 1874, his son André-Hippolyte Sténosse was born. Like his father, he also studies at the Conservatoire and leaves the class in 1894 after a second accessit. He joins the Musique de la Garde républicaine and later probably also gets a position at the Opéra Comique. Judging by the newspaper reviews, he is a better flute player than his father. This is probably also proven by the fact that he was the first flute player at the Opéra from around 1914. Since the newspapers rarely give first names and make no distinction between father and son, it is difficult to tell them apart. Presumably, the flute player after 1891 is primarily the son and not the father.

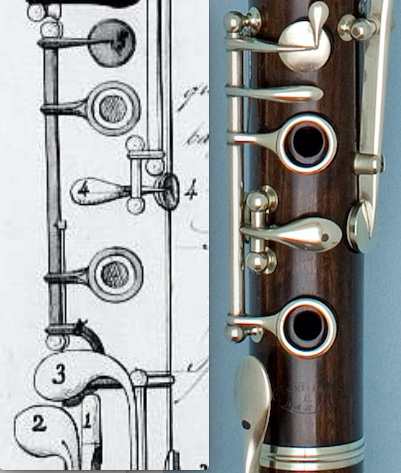

The flute in this video was made in the workshop of Georges Félix Remy and his brother Nestor in Mirecourt, about 370 km south-east from Paris. René Pierre has already done extensive research on this flute maker for his blog, so I’ll just give some key points here. Mirecourt was known for the production of stringed instruments, not so much for wind instruments. Around 1846, Georges Félix probably took over the workshop from the Leroux family, originally from La Couture Boussey. The second name on the stamp Genin comes from his wife. He probably added it to distinguish himself from the Remy violin makers. In 1852, his wife died and he remarried. In 1863 he took over the workshop of another instrument maker Ferry, at the latest at this point Remy must have changed the name on his stamps.

The flute is not one of the very exquisite instruments, but it has an interesting key system. It serves to open the F# key automatically when F# is fingered. This system has the advantage that the F# as a leading note is never too low.

On 13 December 1853 Jean Rémusat (first prize winner in 1832) patented several improvements to the flute, including an open F-sharp key regulated by means of ring keys. (source: INPI, brevet 17893) Rémusat describes the mechanism as follows: „No. 5, open F-sharp key. This key has a bridge under the ring of the natural E hole that runs under key no. 3, can maintain the C sharp, the D and the A of the third octave without changing the fingering and without changing the sound. This key (no. 5) has the advantage of correctly reproducing the F sharp of the three octaves and the natural G of the third octave.“

The mechanism of the Genin flute is strikingly similar to Rémusat’s invention, but one detail is missing. A small lever under the D sharp key ensures that the F sharp key is closed when the D sharp key is open. In this way, the fingering for F#3 (XOO/XOO/o), F3 (XXO/XOO/o) and C#3 (OXX/XOO/o) can be used without problems. Without the lever F3 (XXO/XOO/o) and C#3 (OXX/XOO/o) do not work because of the automatically opened F# key. C#3 (OXX/XOO/o), D3 and A3 are indeed very high, and so is F#3 (XXO/XOO), moreover, it sounds bad. As an alternative solution for closing the F#-key Genin added another lever and a nose that is attached to the key flap, however, these are not usable in fast passages and some tone combinations (e.g. E3-F3). It was a great challenge to get to know the instrument and find fingerings that worked within the 12 days of preparation and very little practice time.

Today, only very few flutes with this key system are known, among others by Godfroy and Nonon.

*1 Tulou (Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung 26.1.1821), 2 Taffanel (La Presse musicale 15.2.1866), 3 Tulou (Revue Musicale 1829, vol. 5, p. 178), 4 Dorus (La Sylphide 6.12.1840), 5 Tulou (Revue musicale 1829, vol. 5, p. 135), 6 Taffanel (La Presse théâtrale 16.2. 1865), 7 Tulou (Revue musicale, 1.4.1834), 8 Dorus (Gazette musicale de Paris 8.2.1835), 9 Dorus (La Presse 13.3.1841), 10 Taffanel (La Gironde 3.4.1865).