On 8 August 1845 Le Commerce reports: “The sixth session of the public competitions of the students of the Conservatoire de musique et de déclamation was devoted today to the wind instrument competitions. The jury was composed of M. Habeneck, president, and Messrs Carafa, Ambroise Thomas, Dorus, Colet, Mengal, Verroust, Prumier and Ruteux (…) 4th competition: flute; the 1st prize was awarded to M. Demersseman; the 2nd to M. Blanco; M. Couplet obtained an accessit.”

Jules-Auguste-Édouard Demersseman, born in Hondschoote (Nord), on 9 January 1833 into a family of tanners, shows musical talent at an early age. He is sent to Paris at the end of 1844 aged eleven (or twelve) to study with Tulou. Tulou attests him a beautiful tone of the flute, lightness and taste. Demersseman stays in the flute class for only three quarters of a year and immediately wins a first prize in his first concours. This makes him the youngest student to win a first prize between 1824 and 1860. In the same year he also receives a second prize in solfège, followed by a first prize the following year. At thirteen, Demersseman is still too young for an orchestral post. Perhaps that is why he (or was it his family?) decided to stay at the Conservatoire and study harmony (1846-49) and later counterpoint and fugue. He finishes harmony without a prize, for counterpoint and fugue he acquires a first accessit in 1852, but also finishes this study without a prize. Demersseman has great ambitions as a composer. In 1854 and 1855 he applies for the Prix de Rome, is one of the six candidates in the final round both times, but ultimately does not win a prize. In 1856 Jacques Offenbach announces a competition for the composition of an operetta. In the 1857 season it will be included in the programme of the Théâtre des Bouffes Parisienne. Demersseman also applies for this, but is beaten by Georges Bizet, then only eighteen years old, and his fellow competitor Charles Lecocq.

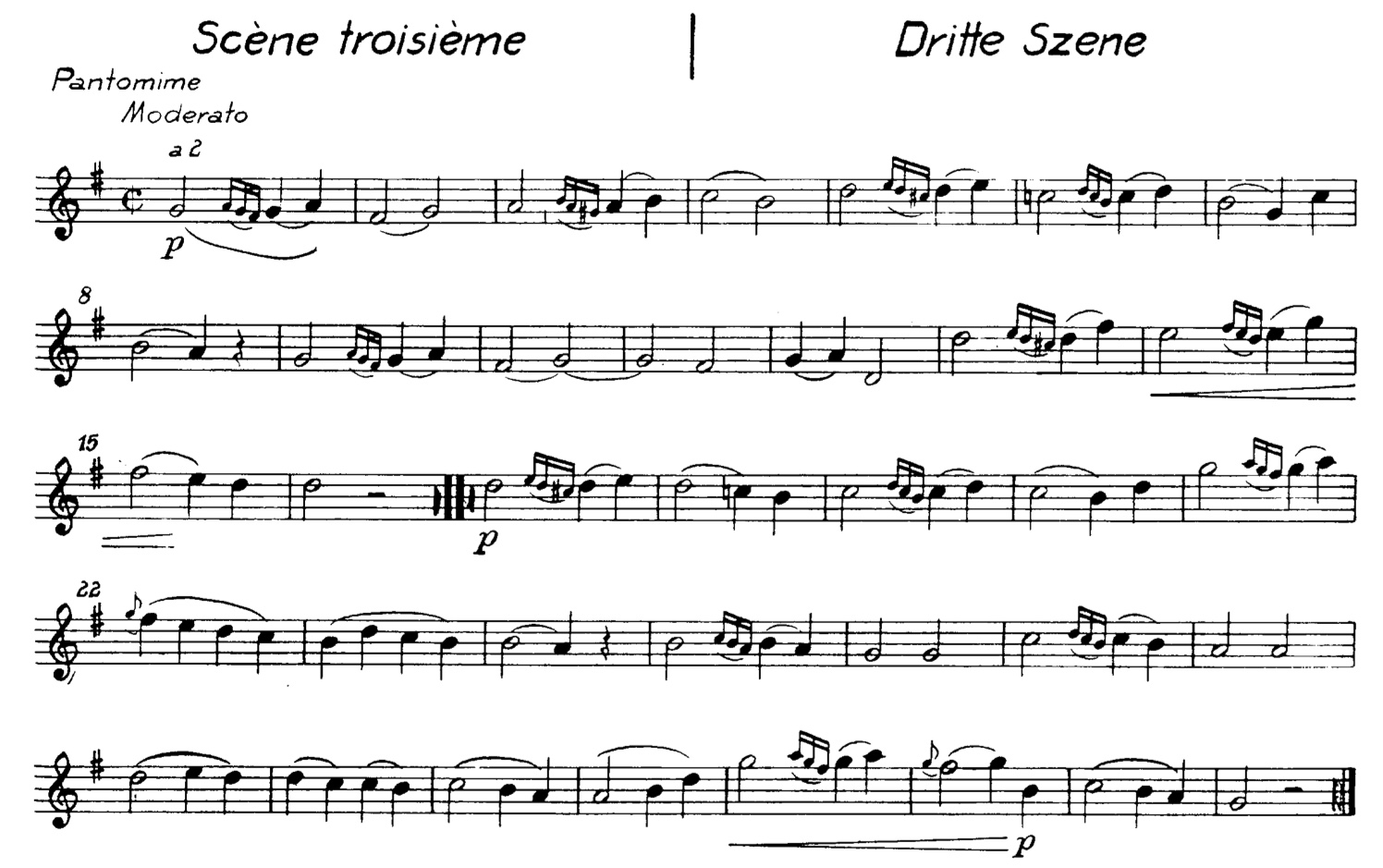

In the meantime 24 years old Demersseman earns his living as a flute player. In the years that follow, he plays in various orchestras and concerts, appearing among others in the Société des Jeunes Artistes under the direction of Pasdeloup as a flute player and composer. From 1856 he is a member of the new concert series Concerts Musard founded by the conductor Alfred Musard at the Hôtel d’Osmond. He performs in almost every (almost daily) concert during the concert season, playing in the orchestra as well as soloist with his own compositions, fantaisies or airs variés. The concert programme alternates between solo pieces with various wind and string instruments and lighter fare in the form of quadrilles and overtures. In 1857, the concert series is renamed Concerts de Paris, and the orchestra is now also conducted by the cornetist (cornet à piston) Jean-Baptiste Arban. The concerts are extremely popular with the Parisian public. In summer, they take place in a pavilion in Ranelagh Park near the Bois de Boulogne just outside Paris and attract up to 2000 listeners. They begin at 20h30 and last two and a half hours. At eleven o’clock in the evening, a special train brings guests and musicians back home to the centre of Paris (on that link you find a photograph of the music pavilion probably from around 1900, it might still be the same as 50 years ago)

The audience and critics are enthusiastic about Demersseman. On 12 January 1858, the newspaper Vert-vert writes: “Mr. Demersseman is an incomparable flutist for the finesse of his modulations as well as for the fullness he knows how to give to his instrument when he makes it sing: a very rare quality, and one that belongs only to a true artist to possess, the flute being, when it is badly played, – let us be forgiven the word – a rather thin and rather shrill instrument.” Le Ménestrel reports on 7 November: “Mr Demersseman’s talent triumphs over these impossibilities: breadth and purity of sound, – agility, equality of fingers, – clarity of articulation, – expression, feeling, he has all the qualities of a virtuoso.”

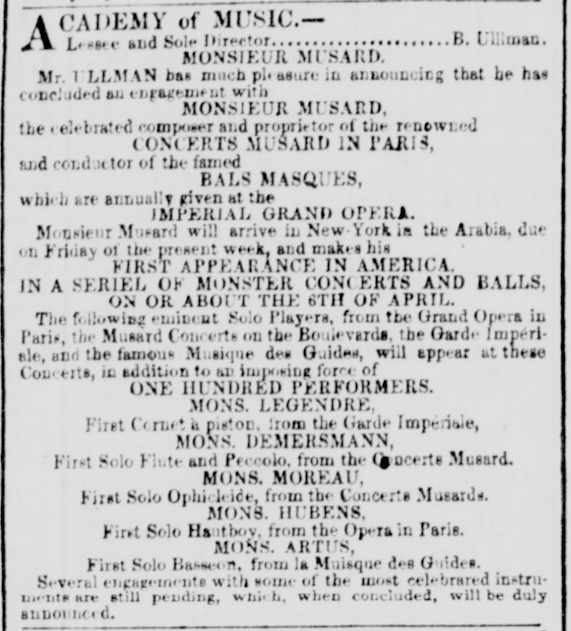

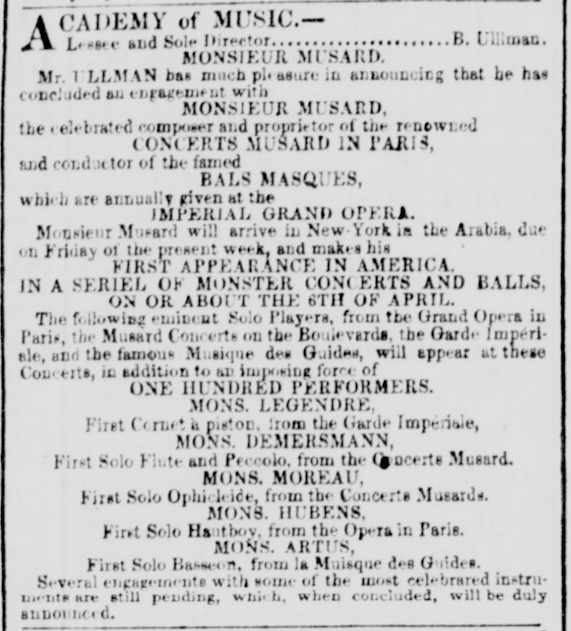

The year 1858 begins with great expectations. In February, Alfred Musard receives a contract for 40,000 francs to stage a concert series at the Acadamy of Music in New York the following season. Musard plans to bring some of his soloists with him, including the cornetist Legendre, the ophicleidist Moreau, the oboist Hubans, bassoonists Artus and Demersseman, in order to have them perform as soloists and to strengthen his monster orchestra, which is founded there. Advertisements appear in New York newspapers (as the following one of the New York Daily Tribune from 18 March) announcing their coming.

In the end, only Legendre and Moreau accompany Musard to America, Demersseman remains in Paris. He continues to perform at the Concerts de Paris and composes a symphony which is premiered in October. In January 1860, Pasdeloup programmes it in his concert series. Unfortunately, the symphony has not survived. Music critics differ in their opinion of the new composition. To some, its style reminds them of Beethoven, to others of Haydn. The first movement, Introduction et Allegro, is said to be more of an overture with flute solo than an orchestral movement, the second movement, Andante, seems very well done, the Scherzo does not please everyone, being a complete contrast to the first two movements, but is also described as a coquettish, dapper and elegant little piece. Finally, the finale is a lively piece with a cello melody and pizzicato accompaniment and a short fugato (Le Monde illustré 6 November, Le Ménestrel 7 November 1858, Niederrheinische Musik-Zeitung 18 August 1860).

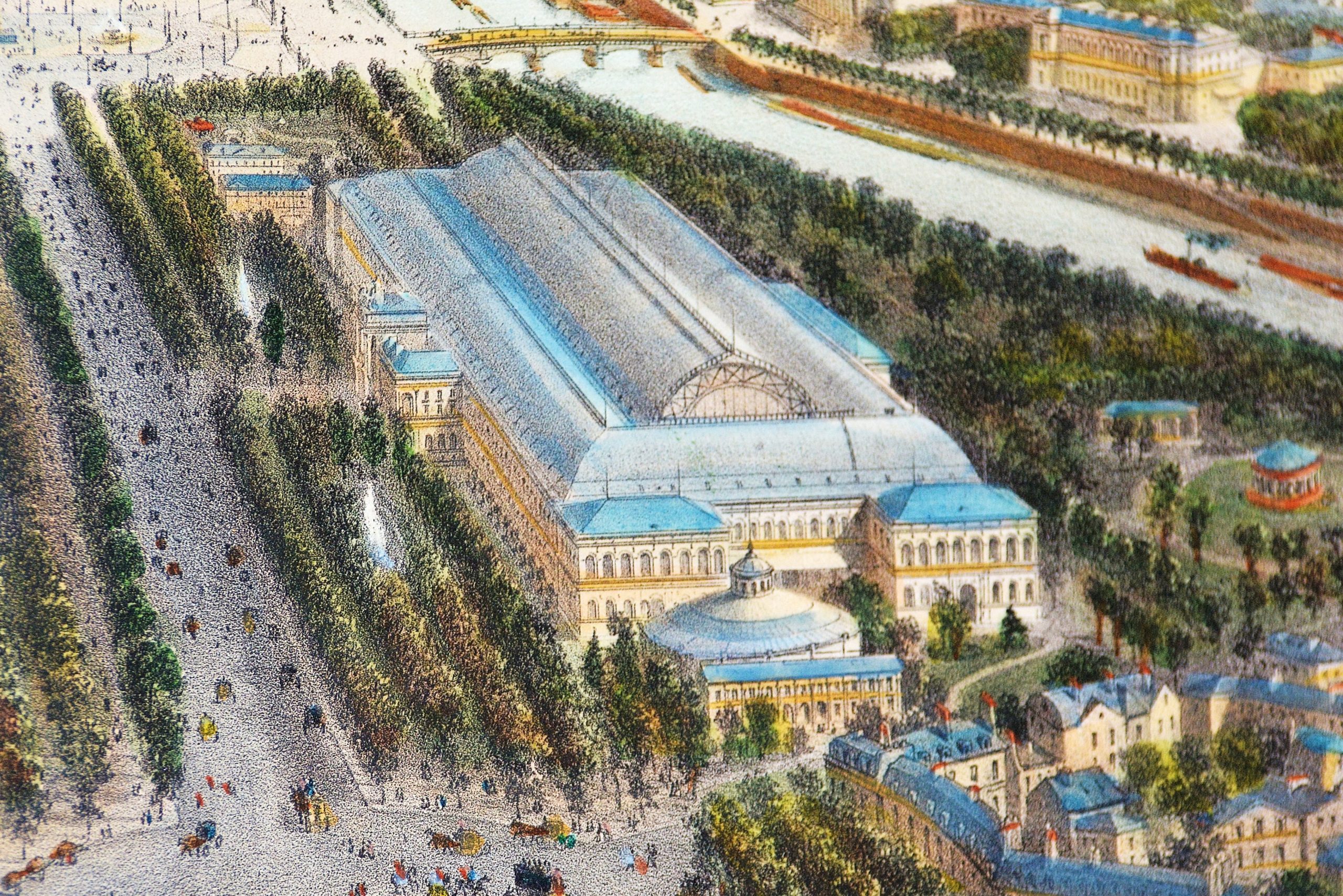

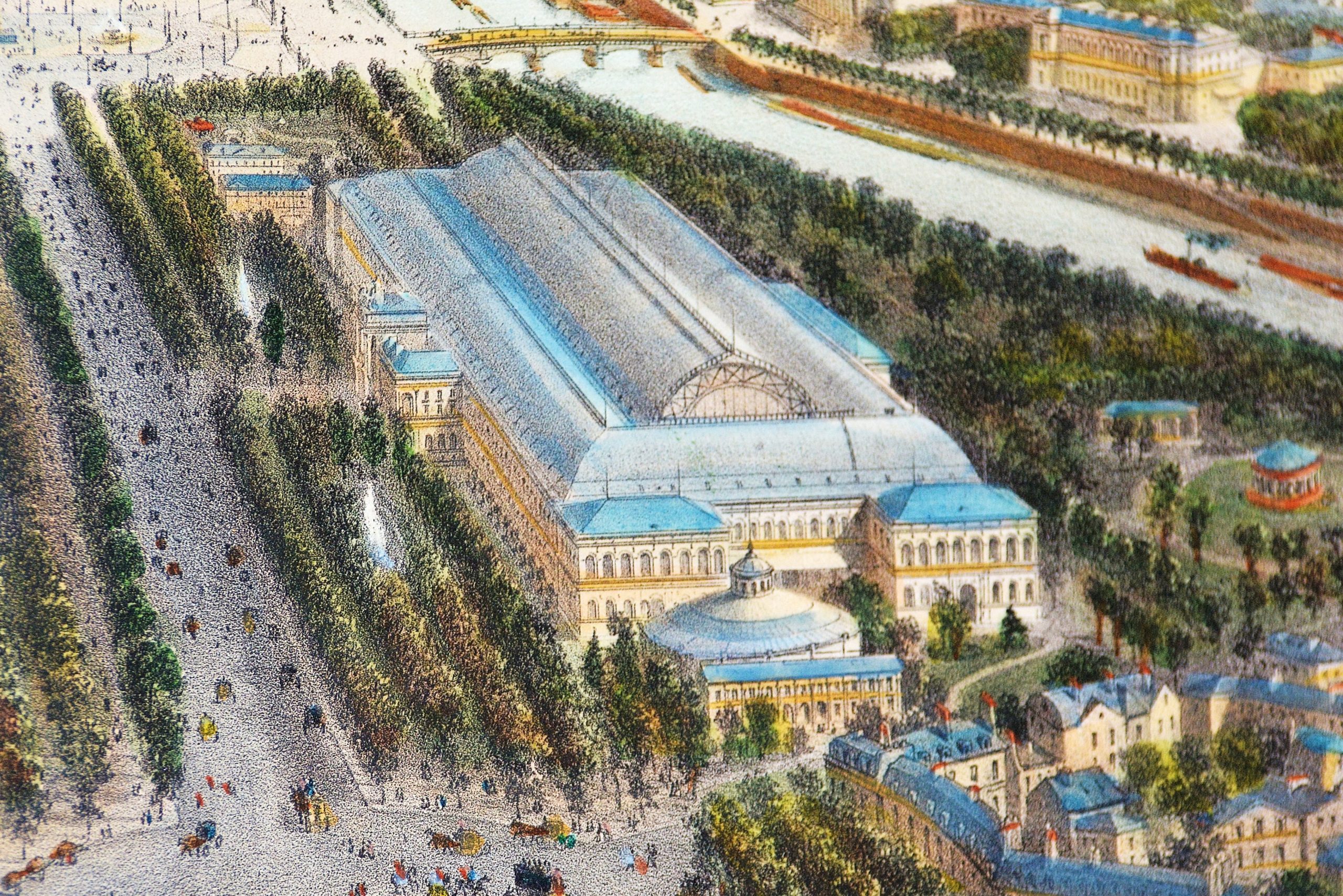

From the summer of 1858, Victor-Florentin Elbel conducts the orchestra. Elbel conducts it until April 1859, after which the second conductor, oboist Hubans, takes over. At this point, Demersseman leaves the orchestra and Miramont (first prize winner in 1839) takes his place. In the meantime, Musard returned from America and resumed his work as conductor of the orchestra. Now the summer concerts take place in a pavilion on the Champs-Elysées behind the Palais de l’Industrie. The orchestra might have played in the little red pavilion at the right site of the following lithography.

The Palais d’Industrie with its huge park and the little pavilion don’t exist anymore. Today, the Grand Palais stands in its place, and the park had to make way for wide streets.

The concert series can again build on the success of the past and is as popular as before. Demersseman is once again one of the stars of the orchestra. On 3 December 1859, we read in the Journal de Seine-et-Marne: “What can be said of Mr Demersseman’s talent on the flute? It is velocity, lightness, ardour, a splendid string of pearls standing out and rolling in space.”

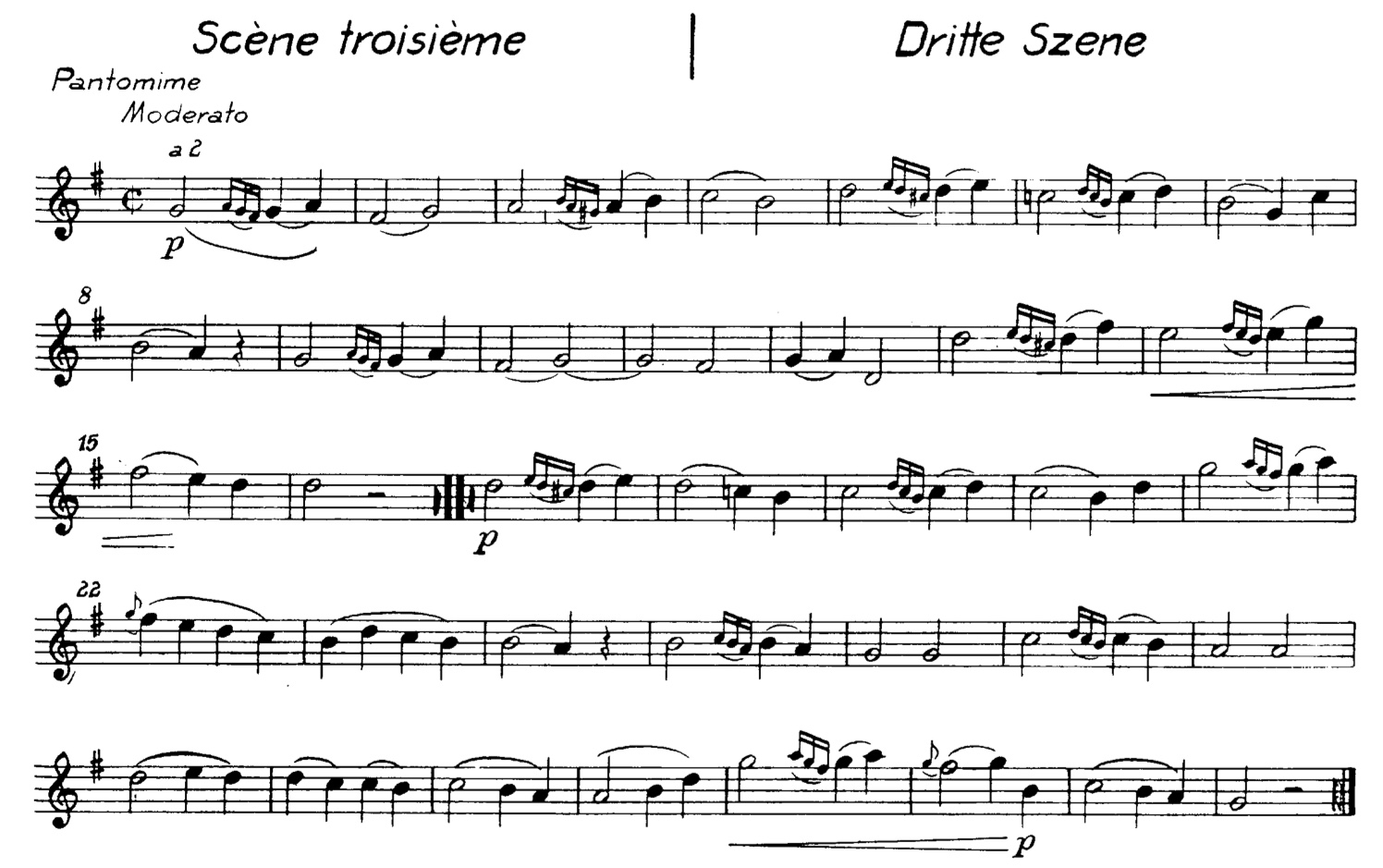

In 1859 Demersseman composes the operetta La Princesse Kaïka for the théâtre des Folies-Nouvelles. This work, as his symphony, has not survived because, like most of his orchestral works, it was not published. An exception is Une fête à Aranjuez: fantaisie espagnole for orchestra with solo violin(?). This work was still very popular in the early 20th century and was arranged for various instrumentations. In contrast to the orchestral works, his flute works were regularly printed from 1858 onwards. Demersseman was not only played by Demersseman, but by other flute players such as Amédée de Vroye or later Rudolph Tillmetz. From the end of the 19th century, more and more flute players include Demersseman’s works in their programmes. Demersseman not only composes for the flute, but also devotes himself to the new instrument family of his friend Adolphe Sax: from soprano to double-bass saxophone, for cor sax à trois pistons et a tubes indépendants, trombone and trompette sax à six pistons et à tubes indépendants. Some of his works serve as concours works for these instruments.

While Demersseman probably composes during the day, he plays in the evening in the Concerts des Champs-Elysées. In 1863 he performs in a festival in Rochefort. The local newspapers outdo each other in praising the Parisian flute player:

“What incredible and prodigious agility of the fingers and the strokes of the tongue! How he detaches these myriads of notes that flow in a murmur like a stream. – One can distinguish everything, one can hear everything, and under this uninterrupted cadence, the song is heard perfectly clear and distinct. (…) Despite all the seductions of the silver flute, Mr Demersseman has kept the old flute.” (Le Nouvelliste de La Rochelle).

“Many revolutions have transformed the flute, one wanted to give it more brilliance, a more metallic sound; but it must be said that, by these successive modifications which have provided the instrument with certain resources which it lacked, one has distorted the essential character of the flute, by depriving it of its primitive sweetness. Mr. Demersseman did not want to abandon the old flute; like the great artist that he is, he plays on the unmodified flute all the difficulties that were considered impossible to tackle until then.” (L’Indépendant de la Charent-Inférieure)

And the praises do not stop in other Paris concerts either:

“Let us add to this tour de force a quality of sound reminiscent of that of Tulou, and, moreover, a manner of phrasing, an art of nuancing and a sensitivity of such a nature as to make one love an instrument for which Cherubini professed so little sympathy.” (Le Ménestrel)

“Here is Mr Demersseman now, with his unmodified flute in his hand… (…) The tricks of this flutist are unbelievable; he finds a way to play a duet with his magical instrument (playing his Carnaval); he accumulates difficulties, and what is worse, charms, ravishes, subjugates, leads.” (La Comédie)

“Demersseman is the public’s cherished and spoiled virtuoso.” (Vert-vert 1864) “Demersseman transports us with his winged flute.” (Vert-vert 1865)

“Everyone knows the immense talent of this flutist. His air varié is peppered with difficulties which he handles with ease. It is as if one could hear the nightingale performing its endless variations in the groves around you.” (Vert-vert 1866)

Unfortunately, the nightingale already falls silent in its prime. On 1 December 1866, at the age of only 33 (the newspapers write 35), he died with great probability of heart failure (not of tuberculosis as most people assume). A detailed obituary in the newspaper Le Soleil of 3 December describes (probably a little too pathetically, but nevertheless revealing) the last ten days of his life:

“Ten days ago, he felt a pain in his left arm; this pain, although slight, worried him, because it bothered him in difficult passages. Two days later, this pain had spread its centre of action over the whole arm, the hand and part of the chest: a joint rheumatism quickly ankylosed the attacked parts and the unfortunate artist soon found himself completely lost. Atrocious pains made his nights unbearable: sometimes, in a fit of delirium, he tore up shirts, sheets, curtains, everything he had at hand. Finally, yesterday, feeling like he was dying, he asked for his flute, the dear one he had loved so much and which gave him back so well. His poor fingers, overcome by pain, could not move on the instrument, which for the first time rebelled against its master: his breath betrayed his desires and from this miraculous flute came, alas! Screaming sounds that brought tears to the eyes of those present. Ah, he was very ill! As he handed it over to Arban, his friend, who was sitting at his bedside, the artist said only these words: “It’s over, I won’t play it anymore, I feel that everything is out of place. Remember what I tell you, my friend;” then with a sob: “Arban, my friend, do not abandon me!” Yesterday he asked for a priest to come to him; then took place between the artist and God that supreme conversation which the dying say in heaven. A dreadful crisis overtook him towards midnight, he suffered until five o’clock, and then he breathed his last. Demersseman was thirty-five years old.”

Pierre-Eugène Blanco, born on 17th January 1826 in Poitiers (Vienne), was 20 years old when he won the first price at the 1846 concours. Blanco started studying the flute at the age of 15. He was an average student who fought with several issues as we read in Tulou’s reports: „works with zeal but makes little progress. His embouchure is quite good and his tongue, with study, becomes lighter (1842); Embouchure quite good, no equality in the fingers, tongue not very easy, no accent in the execution and no progress (1843); being often ill, has made little progress; has made little progress in spite of his zeal for work. (1844); his musical organisation does not give great hope for the future and yet he has made some progress this year; very accurate in class, works well, has made much progress. (1845); very accurate in class, works fairly well, has made some progress. (1846)“ Right after his studies he got employed as flute player in the Théâtre Délassements – Comédie. It is not known how long he held this position. In 1850 his name appears in a report about a possible affiliation of the music section of the society for the arts and industry of Poitiers with the Association des Artistes musiciens in Paris (Revue et Gazette musicale 23 June 1850, p. 215f), so he might have returned to his hometown. However, I didn’t find any information about his further career.

Jules-Adolphe Couplet, born in Ath / Belgium on 10 May 1823, is 21 years old when he enters Tulou’s class. After having made good progress in the first year his reports get less optimistic. Tulou notes: “progressing with difficulty; works with zeal; but his progress is not very noticeable (1845), more eager to do well, but his embouchure is difficult and his fingers are heavy; hard-working, but his progress is not very noticeable (1846)”. Couplet gets an accessit in 1845 but leaves the Conservatoire a year after. He plays in the Orchestre de la Porte-Saint-Martin and Théâtre Délassements – Comédie and becomes a teacher at the Imperial Institute for the Young Blind. Like Demersseman he is a fervent composer – he writes hundreds of melodies, romances and chansonnettes – and dies young, with only 37 years.

The 11th Grand Solo is one of Tulou’s easier concours works. I recommend it to anyone who is studying the simple system flute today. D major plays well, the middle section Andante sostenuto in B flat major is short and contains no complicated fingering combinations. There are none of the usual complicated trill passages, and even the final virtuoso passages are not technically difficult. Perhaps the challenge lay more in the long sustained notes at the beginning as well as in the three cadenzas, which certainly had to be improvised by the students.

Tulou dedicated the Grand Solo to his friend H. Ritter. Unfortunately, I have not found out who this H. Ritter was. As far as I know, there was no one by that name among his fellow musicians. Charles-Émile Ritter studied with Tulou from 1853 to 1857. No other musician is known from his family, Émile’s father Georges Ritter, a tailor, cannot have been either. In the 1840-50s a flute player Heinrich Ritter from Berlin travelled through Germany and Austria. His flute playing received extremely controversial reviews, ranging from “masterful” to “tasteless”. It is rather doubtful that Heinrich Ritter ever visited France and became Tulou’s friend.

The flute in this video comes from the eldest son of the famous Clair Godfroy ainé, Frédéric Eléanor Godfroy ainé. He probably learned the skill from his father and opened his own workshop in 1827. He did not work in the flute business for long and closed his workshop as early as 1844, which is why his flutes are relatively rare to find nowadays. Externally, the instrument, which was probably made around 1830, does not differ from Godfroy ainé’s. But if you hold it in your hand, you will notice a slightly different ergonomics. The keys are placed a little differently and are somewhat less comfortable. The tone of the flute is typically French. With its thin bore, the third octave plays easily, the low register is a little less strong. Intonation-wise, the flute is rather challenging. It took me a few days to get used to it. As on many flutes, D/Eb1 and D/Eb2 are very low, A2 and C3 (OXO/XXX/o) are very high, F#3 has to be fingered with XOO/XOO/o and A3 with OXXo/XXO. For F3 I had to fall back on the fingering XXoO/XXO/o, which does not appear in Tulou’s method but is used by Walckiers and Berbiguier.

The piano is a 1843 Pleyel.

“The flute competition also deserves a special mention: only three competitors were vying for the prize, and the youngest of them all, a child of twelve or thirteen years of age, who started out as a ship’s boy, and who is already an excellent musician, won by a landslide over his two competitors. The piece composed by Mr. Tulou was also very pleasant.”

The young Gustave Lemou visibly impressed the author “A.Z.” of the article in the Revue Musicale from 13 August 1843. In fact, Lemou, born on 23 November 1828 in Auxerre, was 14 years old when he got the second price in the 1843 concours. In the same year he also held a first price in solfège. Lemou was an outstanding flute student as Tulou reports: „has made noticeable progress in the short time he has been in my class (1842); very good reader, easy embouchure, light fingers, gives a lot of hope; gives hope, works quite well (1843), did not work as hard this year; but nevertheless has made remarkable progress; he is in very good health. (1844)“ In 1844 Paul Smith mentions him in his report about the concours: „Flute. – First prize: Mr. Lemou, a young student barely sixteen years old, and to whom we would give at most twelve, who started out as a ship’s boy, and has only been at the Conservatory for two years.“ (Revue et Gazette musicale 11.8.1844)

As price winner Lemou could play in the concert of the distibution of prices. In the review of that concert we get more information about his playing: „The young flute player Lemou distinguished himself above all by his charming quality of tone and the elegance of his style“ (Revue et Gazette musicale 24.11.1844). Not only did Tulou highly estimate his playing, other teachers did as well. So did the horn teacher Meifred predict him a brillant future. Although his playing was very promising he later did not appear in the musical press. We only find him in several theatres such as the Théâtre de l’Ambigu-Comique (1845) and the orchestras of the Théâtre Montausier, the Folies-Dramatiques and the Théâtre Dejazet. He died in 1876 or 1877.

François-Émile Lascoretz was born on 14 October 1825 (or 1826) in Troyes. He came from a family of (military) musicians. His father Jean-Baptiste-François-Antoine l’aîné (1786-1854) played the clarinet and composed. He was the tenant of the Café de la Comédie and ran a music school. In 1835 he went to Paris (this could explain his son’s connection with the Conservatoire) and later returned to Troyes, where he taught music and traded in musical instruments. His younger brother Adrien-Antoine-Jean-Baptiste le jeune (1787-1857) was a clarinetist and military musician, like their father.

François-Emile probably received his first musical training from his father, and he might have received flute lessons from the flute player Arnaud, who took an active part in concert life in Troyes. When Lascoretz was 16 or 17, he entered Tulou’s class. Tulou was very positive about his new student. He reported: „fairly good musician, easy embouchure, fairly good tone, lightness in the fingers, I hope he will become a very good student” (1842). A year later, already, Lascoretz took part at the concours. He got an accessit. He might have felt some pressure to finish his studies soon, because they were financed by the city of Troyes, as we learn from an 1845 concert review: “M. Lascoretz fils, laureate of the Conservatoire, played us on the flute variations on a few motifs of the Diamants de la couronne. There is a future in this young man, who has so far shown himself worthy of the sacrifices the city has made to complete his musical education. However he is a little wary of his petulance of young age, he will be able to give more strength and fullness to tone which already does not lack sweetness and harmony.” (L’Aube 3 April 1845). Nevertheless, it will last another two years before he takes part in the concours again. In the middle of his studies, he somehow lost motivation, as Tulou reported: „quite good embouchure and a lot of ease, he would need solfège lessons (1843); has the means to do well, but his shortcomings in class and his laziness prevented the progress he should have made (1844)”. Shortly after he regained his composure and, after winning a second prize in 1846, completed his studies in 1847. Tulou was quite content: “, is fine; but no apartitude in the class (1845); has made significant progress; good embouchure, very easy, fairly good musician; but little apartitude in the measure (1846); good embouchure – bright fingers, good musician; but a lightness that unites with the good quality of his execution (1847)“ The city Troyes celebrated this success as we read in an article of the Troyes newspaper L’Aube on August 4: “The young Lascoretz, who had obtained the second prize for flute at the Conservatoire two years ago [here the author is mistaken], has just completed with dignity a work so well begun, by meriting the first prize, which has just been awarded to him in the solemn session of the August 3. While congratulating the laureate on this fine triumph, we applaud the fact that the sacrifices made by the city, in favor of this young man, have produced a favorable result. It is rare to achieve such honorable and decisive success. We are told that young Lascoretz is to settle in Troyes. We welcome this resolution with pleasure. The crowned Artist will be a useful auxiliary for the Philharmonic Society; and it is likely that with such a background he will not lack pupils.”

Probably during his studies Lascoretz played in the orchestra of the Théâtre de l’Ambigu-Comique. As his father, his uncle and Tulou he was member of the Association des Artistes musiciens. Back in Troyes he played an active role in the city’s cultural life. He played flute in the Orchestre de la Société philharmonique and a few years he became their conductor. Lascoretz also became director of the Orphéon, a musical institution dedicated to singing and music education, and founded a fanfare, which was expanded to harmony music in 1859. He also composed several pieces, including Trois trios faciles et brillants for flute, horn and bassoon, a polka for piano and orchestra (1853) and a chanson politique et patriotique.

In the Société philharmonique he played and conducted the orchestra at the same time as the author of a review from May 15 1859 reported:

“One can see that he is in control, that he is sure of himself, that he no longer has to reckon with those material difficulties that often cause hesitation and deprive the performance of the brio that takes you away, the casualness that charms. (…) Emile Lascoretz, the Proteus of music by his talent, who can be a first-rate flute player, violinist, cellist and anything else you like, if necessary, did even more in Guillaume Tell; he conducted the orchestra and played the part of first flute at the same time: his instrument was a baton, his baton an instrument, and all of this to everyone’s great satisfaction, thus contributing doubly to the unquestionable success of the masterful overture. Rossini would have been pleased to see his favourite work so perfectly performed.”

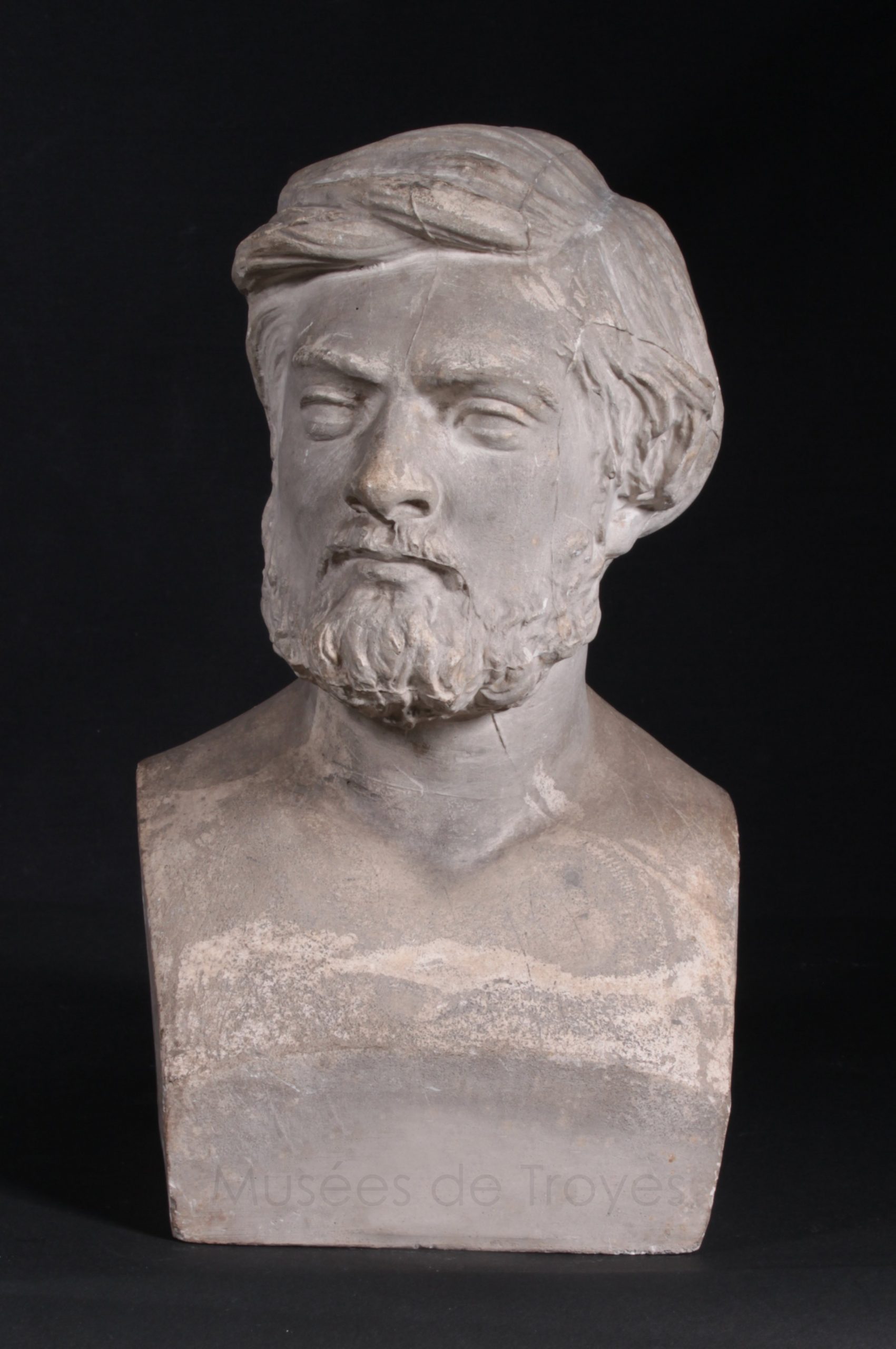

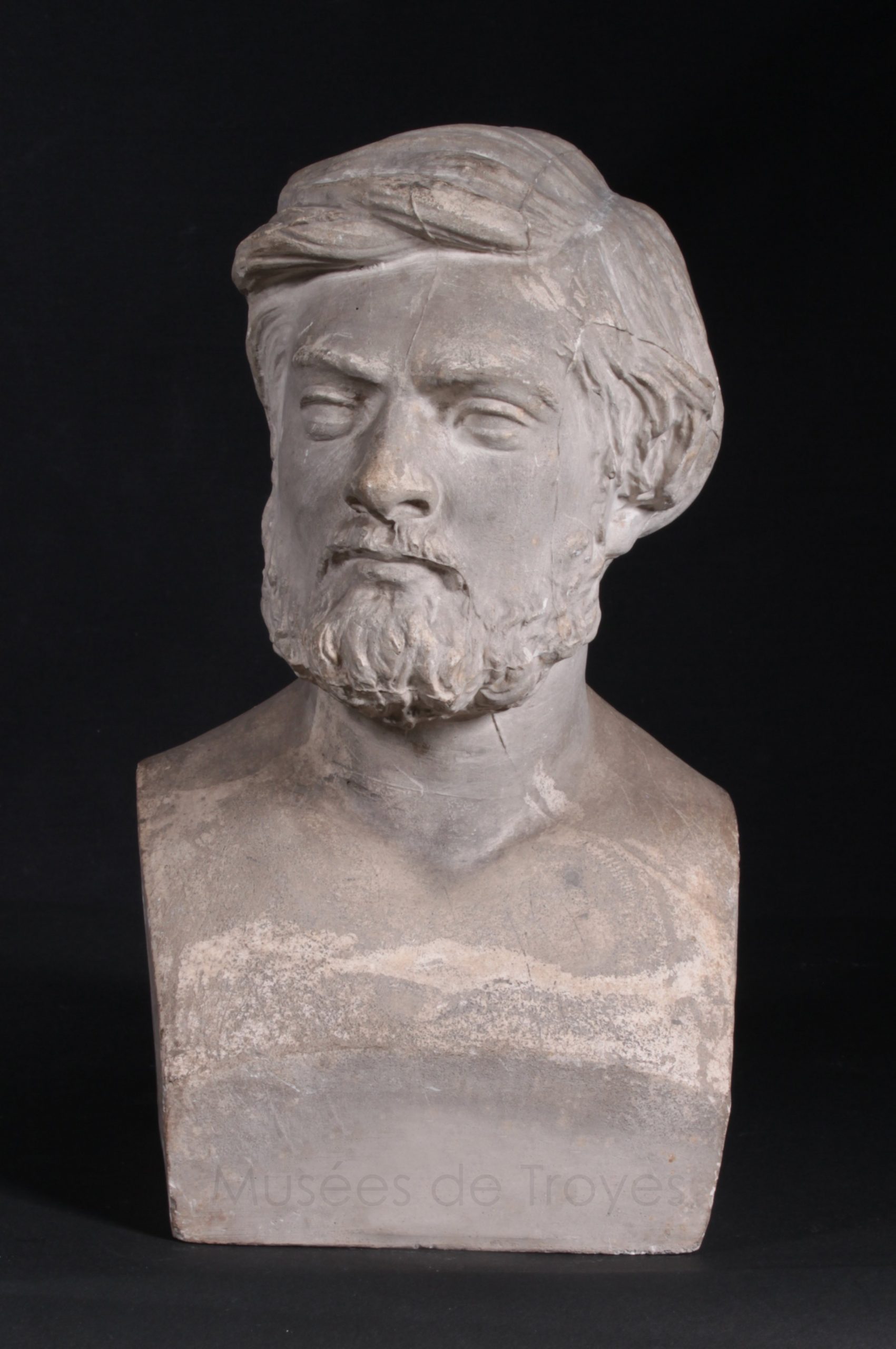

Troyes, musée des Beaux-Arts, photo J.-M. Protte

Unfortunately, François-Emile did not live to be old. He died on 8 September 1860. The Musée d’art et archéologie in Troyes houses a bust of Emile. It was made in 1851 by his friend Louis-Auguste Delécole (1828-1868).

Not much was written about his playing. There is, however, a short note about the choice of music Lascoretz made for a concert in 1855 that tells us rather more about the author’s taste than about the execution: “Mr. Lascoretz, a distinguished laureate of the Conservatoire, who accidentally arrived in Bar(-sur-Seine) during the concert, and who only gave us an improvisation that was a little too fantastic, made us regret not hearing him in a well-chosen and well-prepared piece. Let’s hope that he will make it up to us at the next concert. In our opinion, the difficulties appeal to few people. As for the mass of listeners, it does not matter to them that an artist has overcome the greatest difficulties, for example, by playing the violin on a single string; by touching the piano with the left hand instead of using both hands, or by playing the flute through the nose like certain Polynesian islanders; what they want are sweet and melodious sounds, music that pleases them like that of Donizetti or Auber.” (Le Petit Courrier de Bar-sur Seine 11 May 1855)

Antoine-Auguste Bruyant, born on 14 December 1827 in Pontarlier (Doubs), changed to the oboe class of Gustave Vogt in 1843. He later played in the Orchestre de la Porte Saint-Martin, in the Opéra Comique, in the Société des Concerts and became officier de l’instruction publique in 1899. He died on 12 January 1900 in Bayonne.

Tulou dedicated the 9e Grand Solo to Monsieur P.M. Roselje de Batavia. Very little is known about P.M. Roselje and his relationship with Tulou. Presumably, Roselje was a wealthy Dutch merchant who seems to have had some affinity with the fine arts. The addition of “de Batavia” suggests that P.M. was one of the Roselje frères who had been granted a monopoly to trade in ice in the Dutch colony of the Dutch Indies, now Indonesia, in 1847. Roselje was a member of the Amsterdam society Arti et Amicitae, founded in 1839, an association that promoted the fine arts and still exists today. He was also a subscriber to the magazine Modes de Paris.

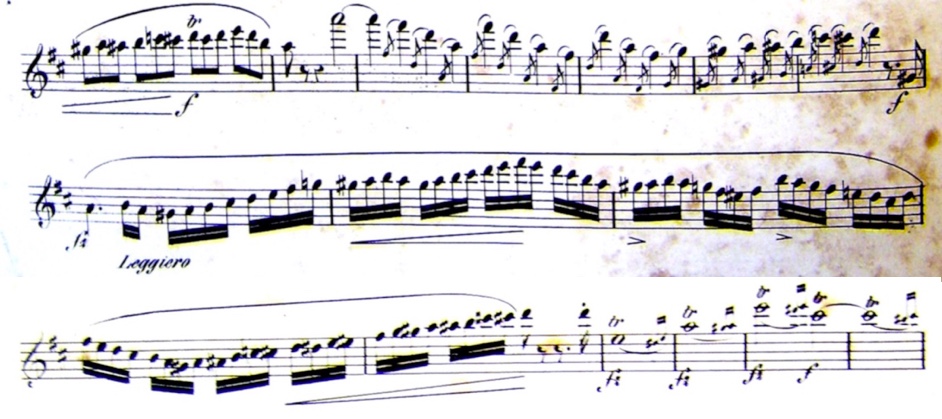

The five-keyed flute is from the Tabard workshop in Lyon. Lyon was one of the centres of French instrument making in the 19th century (more information about Lyon and its instrument makers in the excellent article by José Daniel Touroude and René Pierre). Jean Baptiste Tabard was apparently best known for his military instruments, but it is questionable to what extent his flutes were used in military music. Flutes could hardly compete dynamically with the other essential louder instruments, and illustrations show mainly small flutes (fife, octave flutes). Moreover, most of the instruments preserved today were made of precious materials, which also does not speak in favour of their use in the military. The boxwood flute played here, however, has some characteristics that speak for such a use in the military: it has a relatively high pitch, around 445Hz, and it is rather robustly made. Its tone is not particularly noble, and the extremely low F# makes playing in cross keys unpleasant. B-flat keys, on the other hand, are easy to play. It was therefore very suitable for the 9th solo in E flat major, even though it does not have a long F key. Because of the good-sounding fork fingerings, it is not necessary in most cases. One exception, however, is the following passage E#-F#-E#-D#-E# in the cadenza:

Tulou makes a detour here to C sharp major and A major before returning to E flat major. With this Tabard flute, these modulations are a real challenge.

The piano is a 1843 Pleyel.

On 6 November 1842 the author “R.” reports about the concours: “Flute, class of M. Tulou. First prize, M. Altès. There was only one competitor; but it is not to this circumstance that M. Altès owes the honour he has obtained. This young artist, who is only sixteen and a half years old, is by nature and by education one of the best musicians and most skilful flutists we have heard: only his master could compete with him.”

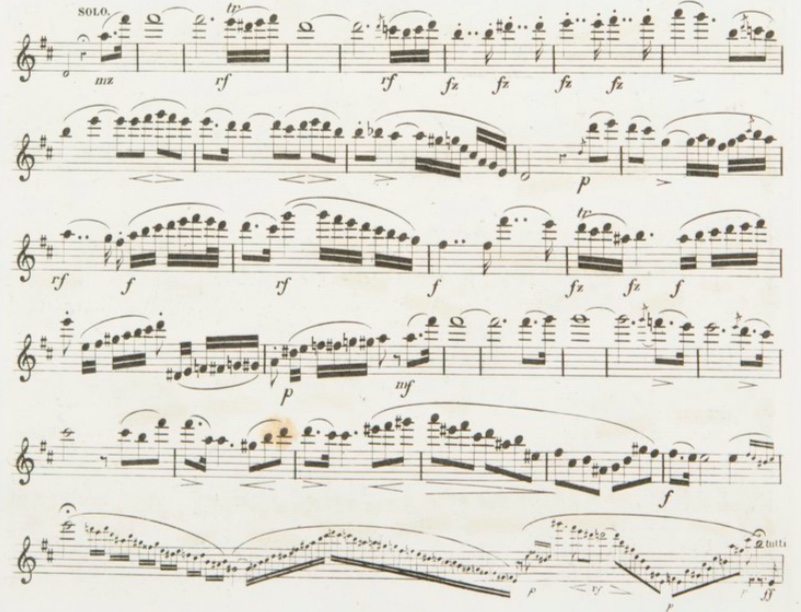

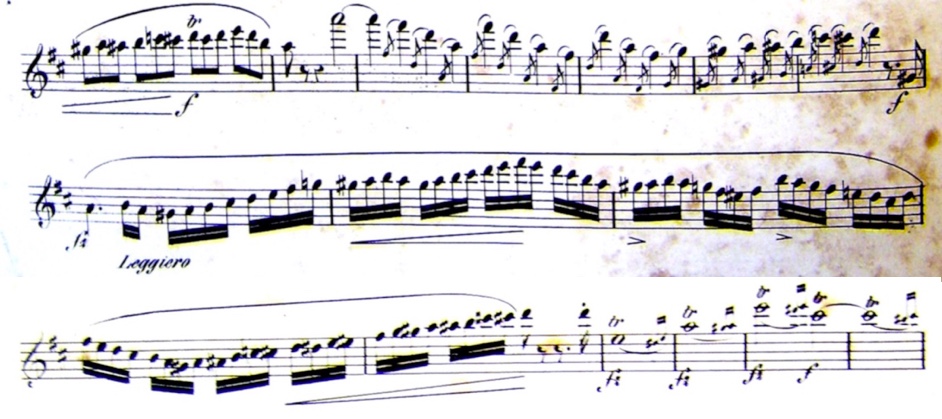

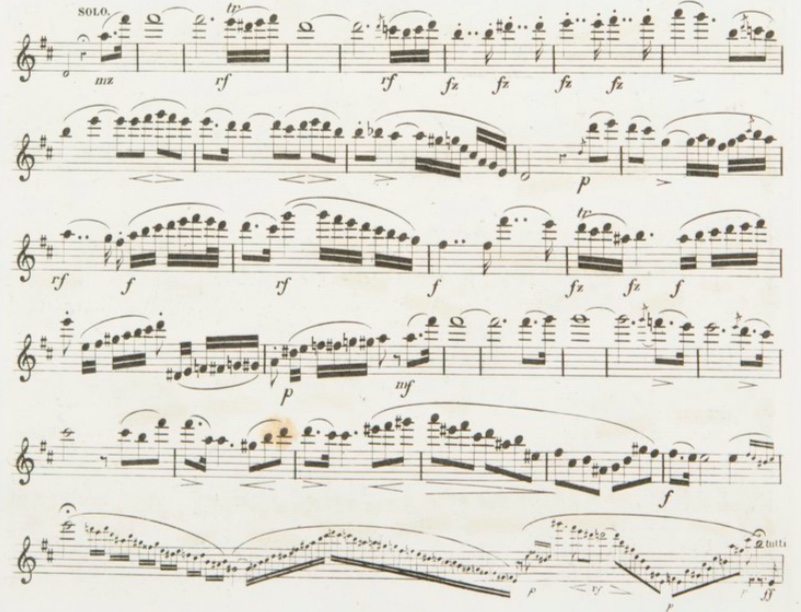

The eighth Grand Solo is a real piece of work. Although it is in the relatively simple key of B minor and has a modest range from D1 to A3, it is technically one of the most demanding concours works. The difficulty lies in the tempo set by Tulou. Tulou’s works rarely contain metronome indications, and in most cases these are within the normal range. For the Allegro of the eighth Grand Solo, Tulou notes 120M.M. for the half note. If one takes this tempo indication for the entire Allegro literally, the tempo means 240 per quarter for the following sixteenth-note passage.

Is it a coincidence that Tulou composes this breathtakingly fast and also shortest grand solo in the very year in which the child prodigy Altès is the only candidate for the concours? The other seven flute students are not eligible: Caillant and Vedrenne (no prize) still have great difficulty with their tonguing and fingers despite some progress, Blanco (1st prize in 1846) works diligently but makes only little progress, Santiquet (no prize) has been in the class for two years but makes hardly any progress, Lemou (1st prize in 1844) is making very good progress, but is not yet ready for the concours, and Bruyant (most probably Antoine Auguste, 1st prize oboe 1849) and Morel have only been in the class since three and two months. It seems as if Tulou had tailored the solo to suit Altès. Altès impressed with his high virtuosity, and this is used wonderfully in this Grand Solo. Did Tulou want to demonstrate with the metronome markings the high tempo at which Altès played the Grand Solo? Or are they an indication that the Grand Solos were generally played at a rather high tempo? Of the concours works, apart from the eighth, only the tenth Grand Solo and the fantasy on Il Trovatore op. 106 have metronome markings. These, however, are in the normal range. As Tulou did not change the metronome marking in the second edition of this Grand Solo, it can be assumed that they are correct. The eighth Grand Solo, however, contains not only virtuoso passages. The introduction is very songful, and the tempo can also be calmed down a little in-between, as for example in the following passage after a short poco ritenuto interlode of the piano.

Nobile or espressivo passages should be played in a somewhat slower tempo. Although in his method Tulou does not give any explanation about these terms, it is evident when playing and reading the score. Sometimes, as in the 8th Grand Solo, the accompaniment slows down before, sometimes Tulou adds an a tempo after these passages. In Nobile passages, tempo rubato sounds less convincing than in espressivo passages. Is it maybe the noble character that does not permit emotional fluctuations?

Joseph-Henri Altès is no unknown person. He was born in Rouen on 18 January 1826. According to Fétis, he began his studies with Tulou on 7 December 1840 at the age of almost 15. Only six months later, he received a second prize, followed by the first prize the following year. Paul Smith was enthusiastic about his talent and predicted a brilliant career for him. Indeed, years later Altès would become solo flutist in several orchestras and, like Tulou, professor at the Conservatoire. First, however, the Parisian public hears him in various concerts. In the early years, he competed with Bernard-Martin Rémusat (four years older) and Jules Demersseman (seven years younger), who were about the same age. In 1849 Hector Berlioz heard him in concert and reported in the Revue Musicale on 4 February: “He really plays the flute in a remarkable way. But this was already known.” In the summer of the same year, another critic in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires wrote in more detail: “He has a very pure tone, an excellent style, and, for agility, he would be able to play sixty-four notes per second, without embarrassment (9 June)” It is precisely this speed of his fingers that makes Altès stand out from the start. It is his great trump card, with which he outshines the perhaps less convincing aspects of his flute playing. On 7 December 1848, Altès marries the singer Émilie-Francisque Ribault, who is seven years younger. At this time he is employed at the Opéra-Comique, but soon after moves to the Opéra, where he will remain until 1876. In 1849 he plays second flute there alongside Dorus. In 1853 he also plays second flute alongside Dorus in the newly founded Nouvelle chapelle de l’empereur (Le Siècle 22.2.1853). Both also play together in the Société des concerts. After Dorus retired in 1868, Altès took over the position of first flute in all orchestras.

That both flute players are a well-rehearsed team is shown by the following report by Berlioz in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires of 24.10.1861 about his revival of Gluck’s opera Alceste: “Messrs Dorus and Altès have found exactly the degree of power that should be given to the low notes of the flute and which covers the melody with such a chaste colouring. Earlier, when I heard Alceste, the first flute of the opera, which was neither modest nor the first in its art, like M. Dorus, completely destroyed this beautiful effect of the instrumentation. He did not want the second flute to play with him, and in order to dominate the orchestra, he transposed his part into the upper octave, thus mocking Gluck’s intention. And they let him have his way. After such an assault, he deserved to be dismissed from the Opéra and sentenced to six months in prison.” The flute player in question must have been Guillou, for the opera was performed in Paris in 1825. Berlioz was 21 years old at the time.

Like Dorus, Altès played the Boehm flute, but it is unknown in which year he changed to the Boehm flute. There is only evidence of the purchase of a Boehm flute from the Lot workshop in 1860 (no. 476).

Altès seems to be completely absorbed by orchestral playing, for he is less often to be found in the Paris newspapers with solo appearances than his colleagues and competitors Dorus, Brunot or Demersseman. Sometimes, together with his brother Ernest (violinist and, from 1871, conductor at the Opéra), he organises concerts in which he performs alongside his orchestral colleagues. On 25 April 1854, it is written in Le Constitutionnel that “Henri Altès, one of our best flutists, performed a fantasy of his own composition on motifs from the Perle du Brésil.” Like so many virtuosos, Altès plays his own compositions. The fact that his works, like those of many flute players, are not of the highest compositional quality is in fact secondary, since they serve above all to put one’ s own playing strengths in the limelight.

16 August 1870 “I have said that the flute class has lost a great deal through the retirement of M. Dorus. The pupils of Mr. Altès all have the same fault as their teacher: they suffer from a poor quality of tone. This defect becomes a real infirmity in the low notes, which are very beautiful when one knows how to play them; Meyerbeer made excellent use of them in the story of the dream in Le Prophet; Berlioz himself was mistaken, and thought he heard two cornets à pistons placed in the blower’s embouchure hole. In the piece chosen for this year’s competition, low notes were avoided. Moreover, the jury awarded the first prize to a student who, because of his temperament, cannot have a very warm or vigorous playing. When I speak of the flute, everyone immediately names Mr Taffanel, and I don’t disagree.“

27 August 1872 “I recommend to Mr. Altès that he stop beating the bar while his pupils are playing the sight-reading piece. It is already too much to indicate the movement before they start.”

8 September 1874 “I suspected Mr. Altès to be, as last year, the author of the flute piece. It seemed to be a fragment of a concerto, as poor in ideas as in construction. Mr Altès amused himself by reproducing I don’t know how many times in the accompaniment a little drawing made up of the first four notes of the air: J’ai du bon tabac (do re mi do). He could have repeated it from one end of the piece to the other, either simply, or in thirds or sixths. Nothing is easier than to make learned music of this kind (…) The flutists continue to be noticed for the mediocre quality of their sounds in general and for the weakness of the low tones. M. Molé alone, who won the first prize, is an exception, no doubt because, as a member of the orchestra of the Champs Elysées concerts, conducted by M. Cressonnois, he is used to playing solos in public and in the open air.”

24 August 1875 “M. Altès gave us a fantasy of his own, which, without being a masterpiece, is nevertheless more acceptable than his other works played in previous years. But he takes his ease in competitions; he speaks of his pupils when he likes and as long as he likes. The sound that the pupils make on their instruments resembles that of their teacher.”

15 August 1882 “Mr Altès kept the quartet to accompany the flute competition. Can’t he beat the measure calmly, without his hands, his feet, his head and his whole body getting involved? It is infinitely too much mimicry. A second prize and three accessits are all that was awarded to a class that remains in honest and respectable mediocrity.”

bust of Altès, now in Paris, musée Carnavalet.

It is very clear that Weber does not think much of Altès. He would probably have preferred to see Taffanel in the position. But there are also positive voices, as the following article in Le Figaro of 3 August 1881 shows:: „The flute class has Mr Henri Altès as its teacher (…he) has been a little prodigy, which is rare among instrumentalists for whom “respiring” is necessary above all (…) he is now content to make very good pupils. His competition this year is proof of this (…)”

Altès is described by his students as a strict and very systematic teacher, who above all adheres strictly to his method. He taught at the Conservatoire until 1893. Taffanel becomes his successor. Altès died in Paris on 24 July 1895.

Altès was immortalised by several artists. The most famous is the painting Les musiciens de l’orchestre by Edgar Degas, in which Altès is playing in the orchestra of the Opéra. Degas also painted a profile view of Altès. Less well known is the bust made by Jean-Pierre Dantan, now in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. By chance, the exact date of its creation is known, for on 1 July 1855, the journalist Eugène Guinot describes in detail in La Presse littéraire his impressions of the artist’s visit to his apartment. There it says: “To go from the bedroom to the salon, you will cross the atelier where we first entered, the one where Dantan usually works. His last three works are there, still in hand (…) two artists’ heads: M. Altès, flute of the Opéra, one of the stars of this brilliant orchestra (…)”. Altès was still playing second flute in the Opéra at this time. Dantan, by the way, was a direct neighbour of Chopin. After Chopin’s departure, Dantan extended his flat by taking over Chopin’s flat.

The eight-keyed flute I play in this video is from Tulou’s workshop. Like many Tulou flutes from this period, it has a good intonation and a very fine tone throughout all octaves, which is not too small but not particularly large either. The necessary keys lie ergonomically and allow virtuoso playing, just the position of the long F-key is a bit too far down for my little finger. However, as it was barely necessary in this Grand Solo it did not bother me very much.

The piano is a 1843 Pleyel.

On 8 August 1841, Paul Smith writes about the concours in the Revue Musicale: “The second session was devoted to all the wind instruments: bassoon, French horn, oboe, flute, ordinary horn and clarinet. Several of these competitions were very remarkable, especially those for oboe and flute. (…) Among the flutists, we saw a younger one appear, smaller than all the others, wearing the uniform of one of our regiments. This child, who is barely fourteen years old, answers to the name of Altès. You cannot imagine with what boldness, what ease, what brilliance, this child fulfilled his double task! M. Moreau, who had also shown great talent, and who counts more years, won the first prize; the young Altès only won the second, but he can be at ease: the first prize will fall to him long before he grows a beard. This is a hope of an artist, who must one day succeed M. Tulou, his teacher.”

Joseph-Félix-Aimé Moreau, born on 24 March 1823 in Dijon, was 18 years old when he won the first price in the 1841 concours. Many Moreaus have studied in Paris, however, their family circumstances are not known. In 1850 he lived in Joigny. Moreau was member of the Association des artistes musiciens. I didn’t find any information about his further career.

Joseph-Henri Altès is no unknown person. He was born in Rouen on 18 January 1826. According to Fétis, he began his studies with Tulou on 7 December 1840 at the age of almost 15. Only six months later, he received a second prize, followed by the first prize the following year. Paul Smith was enthusiastic about his talent and predicted a brilliant career for him. Indeed, years later Altès would become solo flutist in several orchestras and, like Tulou, professor at the Conservatoire. First, however, the Parisian public hears him in various concerts. In the early years, he competed with Bernard-Martin Rémusat (four years older) and Jules Demersseman (seven years younger), who were about the same age. In 1849 Hector Berlioz heard him in concert and reported in the Revue Musicale on 4 February: “He really plays the flute in a remarkable way. But this was already known.” In the summer of the same year, another critic in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires wrote in more detail: “He has a very pure tone, an excellent style, and, for agility, he would be able to play sixty-four notes per second, without embarrassment (9 June)” It is precisely this speed of his fingers that makes Altès stand out from the start. It is his great trump card, with which he outshines the perhaps less convincing aspects of his flute playing. On 7 December 1848, Altès marries the singer Émilie-Francisque Ribault, who is seven years younger. At this time he is employed at the Opéra-Comique, but soon after moves to the Opéra, where he will remain until 1876. In 1849 he plays second flute there alongside Dorus. In 1853 he also plays second flute alongside Dorus in the newly founded Nouvelle chapelle de l’empereur (Le Siècle 22.2.1853). Both also play together in the Société des concerts. After Dorus retired in 1868, Altès took over the position of first flute in all orchestras.

That both flute players are a well-rehearsed team is shown by the following report by Berlioz in the Journal des débats politiques et littéraires of 24.10.1861 about his revival of Gluck’s opera Alceste: “Messrs Dorus and Altès have found exactly the degree of power that should be given to the low notes of the flute and which covers the melody with such a chaste colouring. Earlier, when I heard Alceste, the first flute of the opera, which was neither modest nor the first in its art, like M. Dorus, completely destroyed this beautiful effect of the instrumentation. He did not want the second flute to play with him, and in order to dominate the orchestra, he transposed his part into the upper octave, thus mocking Gluck’s intention. And they let him have his way. After such an assault, he deserved to be dismissed from the Opéra and sentenced to six months in prison.” The flute player in question must have been Guillou, for the opera was performed in Paris in 1825. Berlioz was 21 years old at the time.

Like Dorus, Altès played the Boehm flute, but it is unknown in which year he changed to the Boehm flute. There is only evidence of the purchase of a Boehm flute from the Lot workshop in 1860 (no. 476).

Altès seems to be completely absorbed by orchestral playing, for he is less often to be found in the Paris newspapers with solo appearances than his colleagues and competitors Dorus, Brunot or Demersseman. Sometimes, together with his brother Ernest (violinist and, from 1871, conductor at the Opéra), he organises concerts in which he performs alongside his orchestral colleagues. On 25 April 1854, it is written in Le Constitutionnel that “Henri Altès, one of our best flutists, performed a fantasy of his own composition on motifs from the Perle du Brésil.” Like so many virtuosos, Altès plays his own compositions. The fact that his works, like those of many flute players, are not of the highest compositional quality is in fact secondary, since they serve above all to put one’ s own playing strengths in the limelight.

16 August 1870 “I have said that the flute class has lost a great deal through the retirement of M. Dorus. The pupils of Mr. Altès all have the same fault as their teacher: they suffer from a poor quality of tone. This defect becomes a real infirmity in the low notes, which are very beautiful when one knows how to play them; Meyerbeer made excellent use of them in the story of the dream in Le Prophet; Berlioz himself was mistaken, and thought he heard two cornets à pistons placed in the blower’s embouchure hole. In the piece chosen for this year’s competition, low notes were avoided. Moreover, the jury awarded the first prize to a student who, because of his temperament, cannot have a very warm or vigorous playing. When I speak of the flute, everyone immediately names Mr Taffanel, and I don’t disagree.“

27 August 1872 “I recommend to Mr. Altès that he stop beating the bar while his pupils are playing the sight-reading piece. It is already too much to indicate the movement before they start.”

8 September 1874 “I suspected Mr. Altès to be, as last year, the author of the flute piece. It seemed to be a fragment of a concerto, as poor in ideas as in construction. Mr Altès amused himself by reproducing I don’t know how many times in the accompaniment a little drawing made up of the first four notes of the air: J’ai du bon tabac (do re mi do). He could have repeated it from one end of the piece to the other, either simply, or in thirds or sixths. Nothing is easier than to make learned music of this kind (…) The flutists continue to be noticed for the mediocre quality of their sounds in general and for the weakness of the low tones. M. Molé alone, who won the first prize, is an exception, no doubt because, as a member of the orchestra of the Champs Elysées concerts, conducted by M. Cressonnois, he is used to playing solos in public and in the open air.”

24 August 1875 “M. Altès gave us a fantasy of his own, which, without being a masterpiece, is nevertheless more acceptable than his other works played in previous years. But he takes his ease in competitions; he speaks of his pupils when he likes and as long as he likes. The sound that the pupils make on their instruments resembles that of their teacher.”

15 August 1882 “Mr Altès kept the quartet to accompany the flute competition. Can’t he beat the measure calmly, without his hands, his feet, his head and his whole body getting involved? It is infinitely too much mimicry. A second prize and three accessits are all that was awarded to a class that remains in honest and respectable mediocrity.”

bust of Altès, now in Paris, musée Carnavalet.

It is very clear that Weber does not think much of Altès. He would probably have preferred to see Taffanel in the position. But there are also positive voices, as the following article in Le Figaro of 3 August 1881 shows:: „The flute class has Mr Henri Altès as its teacher (…he) has been a little prodigy, which is rare among instrumentalists for whom “respiring” is necessary above all (…) he is now content to make very good pupils. His competition this year is proof of this (…)”

Altès is described by his students as a strict and very systematic teacher, who above all adheres strictly to his method. He taught at the Conservatoire until 1893. Taffanel becomes his successor. Altès died in Paris on 24 July 1895.

Altès was immortalised by several artists. The most famous is the painting Les musiciens de l’orchestre by Edgar Degas, in which Altès is playing in the orchestra of the Opéra. Degas also painted a profile view of Altès. Less well known is the bust made by Jean-Pierre Dantan, now in the Musée Carnavalet in Paris. By chance, the exact date of its creation is known, for on 1 July 1855, the journalist Eugène Guinot describes in detail in La Presse littéraire his impressions of the artist’s visit to his apartment. There it says: “To go from the bedroom to the salon, you will cross the atelier where we first entered, the one where Dantan usually works. His last three works are there, still in hand (…) two artists’ heads: M. Altès, flute of the Opéra, one of the stars of this brilliant orchestra (…)”. Altès was still playing second flute in the Opéra at this time. Dantan, by the way, was a direct neighbour of Chopin. After Chopin’s departure, Dantan extended his flat by taking over Chopin’s flat.

The eight-keyed flute played in the video is from the Bellissent workshop (1818-42) and was probably made around 1830. Besides the usual six keys (C Bb G# sF D#) it has two curious but quite unnecessary keys. One small key is operated by the third finger of the left hand and serves as a second A-Bb (trill-)key. Another one is operated by the index finger of the right hand and serves as B-C# trill key (the Triébert flute, used in the Marco Spada fantasy has that trill-key as well). Bellissent’s name is probably a little less known than that of Godfroy and Tulou, but nevertheless, he played an important role in the Paris flute market. Just as other flute makers he tried to improve the flute by adding extra keys, using cork pads, mounting the tenons in cork and reinforcing them with a silver ferrule (shown at the 1827 exhibition in Paris). He also made a mechanism to lower and raise the pitch of the flute while playing. Most of features where used by other flute makers as well before him, so Bellissent was rather not their inventor.

The piano is a 1843 Pleyel.