1849 – Tulou, 14e Grand Solo

On July 29 1849 Paul Smith reports in the Revue et Gazette musicale:

“All these brave young people are preparing, with undiminished ardor, for a career that is at this moment very sterile; but what does it matter to them? The future is theirs: the future is always better than the present, that’s the rule, and we strongly hope that the rule will not be misleading in this case. As a general remark, we would say that this year, more than any other, the jury let itself be carried away by sharing and multiplying prizes. For our part, we have always defended the opposite principle, and we were not lacking in arguments; but they are not lacking either to the jury, when it finds themselves faced with several equal talents, between which they do not believe they can choose, without committing a grave injustice. And then, each year, the number of pupils increases, consequently does the number of talents, talents of pupils of course; how not to increase proportionately the number of rewards? (…) Flute. First prize shared between MM. Young Hermant and Ferret; second prize, between MM. Doudies and Brivady; accessit, Mr. Devalois, all students of Mr. Tulou.”

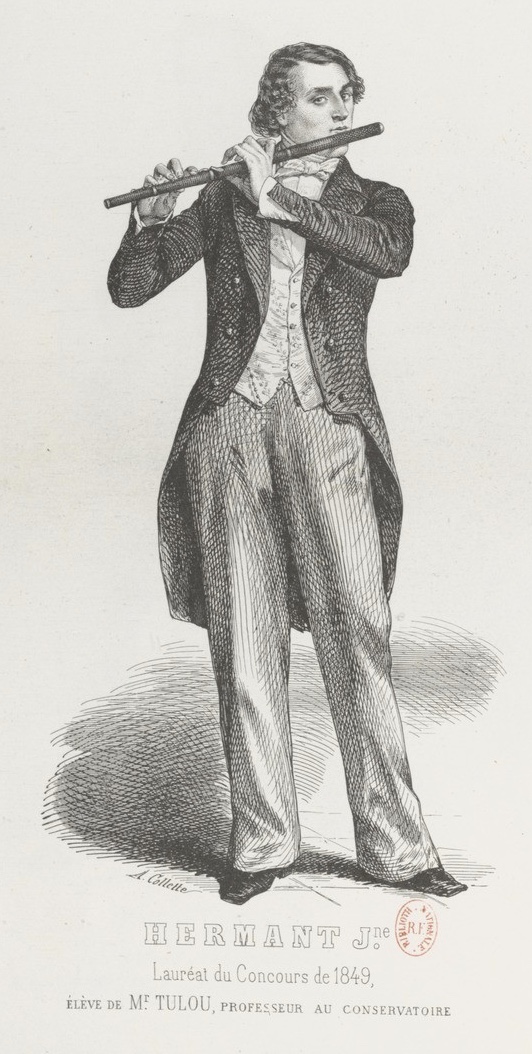

Jules Arthur Hermant (later called Jules Herman) is the most famous student of that year. He appears with a short biography in Adolph Goldberg’s portrait collection of flutists (1906). Although it might have been prettified a little the biography provides us with important information:

Hermant as a young student, source: bnf.gallica.fr / Bibliothèque National de France

„Born on September 26, 1830 in Douai (North), did his first music studies at the local academy and received first prizes for solfeggio, flute and violin. He then went to the Conservatory in Paris, was a student of Allard [Jean-Delphin Alard] for violin for a short time [his name does not appear in the reports in any of the violin classes though], but then entered Tulou’s flute class and received the second prize in 1848 and the first prize in 1849. [According to Tulou’s reports Herman studied in Paris for only two years. Tulou saw great talent in him from the start. He wrote: „has made a lot of progress in the short time he has been in my class, and leads me to believe that he will have an easy talent; gives me a lot of hope (1848), has only been in my class for a few days (?), he has a disposition; very good student – hope (1849)“.] At that time he was a classmate and intimate friend of, among others, Demersseman, Altès, Bruneau and others. [They did not study at the same time. Demersseman finished his studies in 1845, Altès in 1842 and Brunot in 1838.] During his stay in Paris he worked as a flute player in the orchestra of the „Théâtre National“ and in the concerts of the „Jardin d’Hiver“, where he often played solos with great success. As a result of the revolution of 1848 and its aftermath, he decided in 1852 to return to the north of his home country and was asked by the director and conductor of the “Grand Théâtre” in Lille to accept the post of solo flute there. In the same year he became a teacher at the „Gymnasium“ in Lille and in 1854 a teacher at the conservatory there, where he worked until 1902 [he taught the flute and oboe].

His reputation spread very quickly in Lille and he was commonly called the „king of flute players“. During the years 1852 to 1868 he achieved significant successes, both in concerts and in the company of Adelina Patti, Peneo [Rosina Penco], [Erminia] Frezzolini, Mme [Rosine] Laborde and others at the theatre. His student classes were always at a very high level and provided the Paris Conservatory with a large number of students who won first prizes there. Herman is the author of many works for flute, oboe, organ and piano.

In 1879 he was appointed officer d’academie and in 1897 officer de l’instruction publique; In 1897 he received the Knight’s Cross of the Order of King Leopold of Belgium and in 1902 the title of Professor honoraire from the Lille Conservatory. Furthermore, Herman has been a member of the jury for the competition at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels for 26 years and is still active today. [According to the biographie musicale de Douai he was appointed jury member in 1883]“

Hermant as a settled man. Source: Goldberg, Moeck.

Besides his career as flute player Herman was a busy flute pedagogue. He taught not only at the Lille conservatory but also at the Lycée Faidherbe, the Pensionat Saint-Pierre and the school Jeanne d’Arc. He was president of the jury of the musical competition of the Maîtrise Notre-Dame de la Treille where he also conducted the harmony band. In 1910, on his 80th birthday, the city of Lille awarded him a gold medal. Only a year after he died after a short disease.

Despite all the fame, there are only a few testimonies about his playing. On December 10 1863, the Journal populaire de Lille wrote about him: „Herman, first prize winner at the Imperial Conservatory of Paris, first solo flute in our orchestra, professor at our conservatory, is a subject of which Lille can be proud. Who hasn’t admired the fine quality of tone possessed by Mr. Herman, his elegant fingerings, his style, and the exquisite taste of his fermatas [points d’orgue]? M. Herman is the author of very pretty compositions for the flute.“ Interestingly, the author mentions his fingerings (doigté). It is not clear, however, what exactly he meant. Did he praise the choice of fingerings or just the movement of his fingers? It is quite possible that, at that time, Herman had already switched to the Boehm flute on which fingerings do not play an as important role as on the simple system flute.

Today Herman is primarily known for his arrangement of Paganini’s 24 Caprices, but he composed and arranged many more works (see bnf.fr).

Hermant’s grave stone in Lille. Source: Wikisource

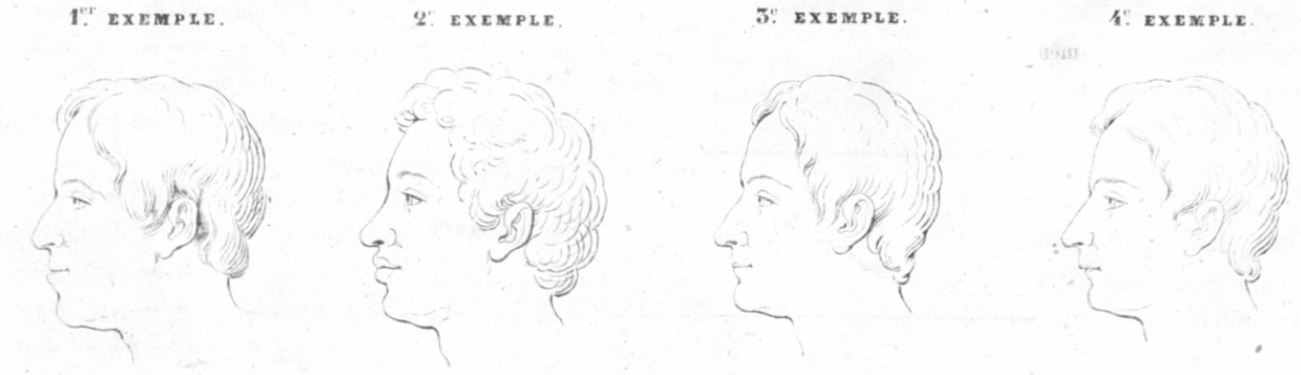

Édouard-Joseph Ferret was born on 30 November 1831 in Béthune (Pas de Cal.). He entered Tulou’s class at the age of 14. Tulou reports: „has only entered the class for a few days – dispositions, but it would be important for him that he had a class of solfège (1846)” Ferret followed indeed solfège for a few years and even got an accessit in 1848, in the same year he got an accessit for flute. Ferret was a hard worker but had a little handicap as Tulou reports: “is not yet very advanced; but working so as to give hopes (1847), made sensible progress; but his embouchure lacks finesse, his lips being very thick and very advanced; makes progress in spite of the difficulty given to him by the conformation of his lips (1848), worker – has made sensible progress (1849)“.

Bad (1,2) and good (3,4) embouchures according to Tulou. From his Méthode de Flûte (1851).

Despite his unfitted embouchure he won a first price a year after his accessit. It did not happen very often that students skipped the second price. In 1850 Ferret was member of the Association des artistes musiciens, an organisation that supported poor musicians, and played in the orchestra Porte Saint-Martin. He later began a career in the military service, became Directeur de la musique municipal du Cateau (Nord) and was decorated as officier d’Academie in 1887.

Vincent-Benoit Doudiès was born in Toulon on 30 May 1830. In 1848 he appears in Tulou’s reports for the first time who describes him as a good student: „made some progress (1848), has ease – makes progress; second prize (1849), has made significant progress, but I believe that his musical organization does not allow him to go further; worker, made progress (1850), good musician – has ease – made significant progress (1851)“ In 1849 Doudiès wins a second price, two years later he finishes his studies with a first price. After his studies he stays a little while in Paris. He is member of the Association des artistes musiciens and plays in concerts here and there. In 1854 settles in Nantes where he gets appointed first flute at the Grand-Théâtre. He does not only fulfill his orchestra duties but organizes concerts, plays flute in a military band and conducts an amateur orchestra. As soloist he plays music by his colleagues (fantasies sur La dernière pensée, La Muette de Portici, a Grand Solo by Tulou, the fantaisie sur Robert le Diable by Walckiers, Souvenir de Paganini by Cottignies a.o.) as well as his own arrangements and compositions (Fantaisie pastorale concertantes, Réveil du Rossignol, fantaisie sur La Traviata, Le cor des Alpes, Une chanson dans le Bois for voice and flute, Romance and Malborough, air varié for piccolo with accompaniment of harmony band). I did not find any of these compositions nor did I find any information about whether his works were published.

Doudiès’ compositional ambitions were not restricted to flute music. He also composed at least three operettas. Croix de Pierre was performed in Nantes in 1860 and Fleur de Genêt in 1862. The ouverture of another opera Wadah was performed in Nantes in 1862 by a military band, conducted by Doudiès. The operettas did not have the succes Doudiès might have wished. In his book Le théâtre à Nantes depuis ses origines Ètienne Destranges writes in 1893 „Croix de Pierre (…) This work proved that in M. Doudiès the composer was far from equaling the flute player” (p.328) and “Fleur de Genêt (…) operetta by M. Doudiès, whose first failure had not discouraged him“ (p.338). None of these works have been published.

In the 1860s he is appointed flute teacher at the conservatory in Nantes. He holds this post until after 1890.

Only little is written about his playing. On July 22 1861 a critic writes in the Nantes newspaper La Phare de la Loire “He draws very pure tones from his flute and makes steady progress. Two solos of his composition made it possible to appreciate the sureness of a playing that the study strengthens unceasingly. His concert piece entitled Réveil du rossignol is full of difficulties which he overcomes with great happiness and accuracy.”

And, last but not least, a quite funny little anecdote about Mr. Doudiès from the Gazette artistique de Nantes 20 November 1890: “M. Doudiès Regarding the concert to be given this week, for the benefit of Mr. Doudiès, I am happy to be able to inform my readers about an unprecedented side by which the beneficiary recommends the benevolent sympathy of his fellow citizens. Mr. Doudiès is not only a talented flute player and a veteran of our orchestra, whose active service he left for health reasons; he is a patriot who, in 1870, gave an example all the more meritorious in that it occurred in the midst of regrettable failings. Although he was over forty, married and a father, he had joined one of the mobilized battalions of our city, and had organized a small brass band there, with four brass instruments at the beginning, but which was increased little by little in personnel and in material: in material, anyhow, because I seem to remember a certain serpent bought on the road, in some small parish.

At the battle of Le Mans, M. Doudiès, although one of the non-combatants, came to line up with the comrades who were defending the tower of Champagné, and fought bravely all day, with a coolness and audacity which I then testify. Typical detail: he had saved his squad’s pot, which he carried on his arm like a cook her basket, and set it down here and there to make the shot. So that of all the battalions, the musicians alone could have supper before going to bed… on the snow. It is therefore not only among music lovers, but also among patriots, that he should recruit his audience. Let’s hope for him that this competition will not fail him. P. Chauvet”

Auguste-Dies-Charles Brivady was born in Perpignan on 29 November 1830. He joins the flute class at the age of 17. Brivady is not a very good student and seems to loose his motivation by the end of his studies. Tulou reports: „made significant progress; has made significant progress on the flute but is still a poor reader (1848), has only recently joined my class. I am satisfied with his attitude and I hope to have a good student; has made progress – is not a good musician and reads with difficulty; second prize, made progress on his instrument but still remained a poor reader (1849), could have made much more progress if he had not been lazy; progress is insensitive, very inaccurate to class; poor organization, made very little progress (1850).“ He does, however finish his studies after four years. There is only little information about his further career. A necrology in Le Ménestrel of 10 April 1904 gives us a few hints:

“From Geneva they announced the death of a French artist who had been very distinguished for many years, established in this city, Charles Brivady, who had made a brilliant position there. Auguste-Dies-Charles Brivady, born in Perpignan on November 29, 1830, had been admitted to the Conservatory in the class of Tulou and had obtained the second prize for flute in 1849 and the first in 1851. After having belonged for some time to the orchestra of the Porte Saint-Martin theatre, he had gone to settle in Geneva, which he never left. A very brilliant virtuoso, he was a member of the theater orchestra and of subscription concerts for a long time, then became a professor at the Conservatoire, where he trained many (une pléiade) of excellent students.“

Eugène-Jean Devalois, born on 10 June 1826 in Paris, was 27 years old when he won the first price at the 1853 concours. He is the oldest documented student of Tulou’s class who finished their studies. His studies have not been without problems. He was already 19 years old when he began his studies at the Conservatoire. Tulou did not take him into his class quite voluntarily as we can read in his report from 2 December 1845. He notes: „is too old to give any hope, and above all is too little of a musician. I have kept him in the class only to satisfy the desire of the Director [Auber] and to be agreeable to the [Louis-Auguste-Michel Félicité Le Tellier?] Marquis de Louvois.“

The Marquis de Louvois was no stranger to the art world (he died in 1844, so it is strange that Tulou still felt obliged to him, or was this obligation to his nephew?). He organized concerts in his house and was a member of the commission spéciale des théâtres royeaux as well as of the committee of the association des artistes-musiciens. Auber was also a member of the committee, Tulou was one of the vice-directors. Moreover, he was a loyal royalist, so it probably seemed impossible to refuse such a request.

Tulou’s concerns did not change significantly over the years, as the following reports show: „low in all; bad musician. Fair sound quality; but very difficult fingers (1846), bad musician – heavy fingers, no facility in execution – little hope (1847), little progress despite his zeal to work, goes to great lengths, without result (1848), poor musician and not very good at playing the flute, still the same – weak, his progress is still slow despite his good will (1849), despite his efforts, his progress is not very noticeable, its progress is not very significant (1850), he is a student who follows the lessons of the Conservatory with accuracy. He works hard, but his progress is slow. (1851)“

In summer 1851 Devalois finally won a second price. This seems to have given him a boost, because the following year Tulou noted: „Zealous student; has made some progress this year (1852)“ In 1853, the time had finally come and Devalois was allowed to take part in the concours. Tulou wrote in the report: „follows my class with zeal – makes good progress“, but later also „zealous student; but his progress is not very noticeable (1853)“. Against all odds, Devalois received a first prize. He fought his way through and completed his studies, not everyone succeeded in this.

His career after graduation is hardly documented. Devalois no longer appears in the press. According to Constant Pierre he later played in the Orchestre du Théâtre Lyrique.

The flute in this video is a flûte perfectionnée, made in Tulou’s workshop. Tulou announced his plan to perfect the flute as early as 1840 during the procès verbaux that took place to answer the question whether the Boehm flute should be taught in the Conservatoire. With this move he was able to convince the commission not to accept the Boehm flute at the Conservatoire for the time being. However, it should take ten years until the flûte perfectionnée came onto the market. Why? After the trial, Tulou was in a very comfortable situation. He won the trial. Victor Coche gave a very bad picture of himself and his model of the Boehm flute made by Buffet jeune, and Vincent Dorus, a rising star in the Paris flute world, adapted the conical Boehm flute (model 1832) to the ideal sound of Tulou. So for the time being there was no reason to continue to perfect the flute. In 1847 a new type of flute, the cylindrical Boehm flute, appeared that could become a lot more dangerous for Tulou. Unlike ten years ago, the Boehm flute in Paris followed just one standard model (in 1840 the commission criticized that there was no standard Boehm model). Tulou’s former criticism that the construction of the Boehm flute was not yet fully developed did not apply here. Furthermore, Dorus was now named in the same breath as Tulou, and if a Dorus was playing the new model, what’s to stop other flute players from doing the same? Tulou may have observed the situation for some time before stepping in and developing his own perfected flute. In 1851, he was already 65 years old, he published his “long-awaited” flute method and presented his new flute at the same time.

This flute belongs probably to a later generation of the flûte perfectionnée. It cannot be determined with certainty whether it was made by Nonon, who left Tulou and ran his own workshop from 1853, or by his successor Gautrot. The key arrangement of the C foot and the C and B keys differ from the earlier models. In addition, its tone is very large, almost a little coarse, and indicates later manufacture. Bindings of some notes do not work as well as on other Nonon flutes. An interesting aspect is the location of the left thumb. It is in the middle between the C and B key on the key flap of the B/C sharp trill key. Unlike ordinary Tulou flutes, the flute player has to reach to the right to operate the Bb key. Another interesting aspect is the close proximity of the D sharp and F# keys. In this way it is very easy to operate the F# key, but you can easily mix up the two keys.

The piano is a 1843 Pleyel. It is highly decorated and is the longest model the Pleyel atelier made.