Hélène-Jean-Joseph Miramont, was born in Masdazil (Le Mas d’Azil / Ariège in the Pyrenees) on October 25, 1823. Seen from Paris, his birthplace is at the other end of the country, on the border with Spain. It is not known how Miramont came to Paris to study at the Conservatoire. Nothing is known about his period of study either. Apparently he already received a first prize in his first concours. This is astonishing in that he was only 15 years old. This circumstance speaks for great talent, for only a few students received a first prize immediately, among them Demersseman (then 12) and Taffanel (15). Nevertheless, little is known of his further career. He played in the Orchestre théâtre Montansier and in the concerts Pasdeloup. Miramont must have gone to Lyon in one of the following years and accepted a position in the orchestra there. However, this move must not have brought him anything good, because in 1851 L’Émancipation published an article in which he describes his predicament:

„Last Sunday’s performance was disturbed by an artistic mischief. Mr. Miramon had less macabre and more reasonable ways of asserting his rights, which we do not wish to appreciate at this time. Here is his justification. N. Tachoires

Dear Editor, In Sunday’s performance, the stage manager came to announce that the audience had missed me and I am not ungrateful enough for that. The audience has so far shown me too much benevolence, its applause is precious to me and I can never do too much to deserve it. I am only sorry that I did not foresee that the absence of a single flute could disturb the performance; I ask the audience to forgive me, and I beg them to read the letter I wrote to M. Mériel, our conductor, on the day of the performance. I think that through the mocking form of this letter, he will understand the state of exasperation in which we are almost all.

To Mr Mériel, conductor.

Dear Sir, I have a stomach damaged by the unhealthy and insufficient food to which the lack of payment has condemned me for so long. I do not want to alarm the maternal solicitude of the director by letting him know that he is putting me on the verge of dying of hunger; however, that is my situation. So I want to postpone this unpleasant moment as long as possible, and for this reason I am conserving my strength and taking a little rest. I have the honour to greet you. A victim of Article 11, Miramont”

Article 11 of the newly, in 1848, created French constitution said: “All property is inviolable. Nevertheless, the State may require the sacrifice of property for a legally established public purpose, and in return for fair and prior compensation.”

We can only speculate what happened to Miramont as a result of this article. Was he dispossessed?

In 1861, he plays one of his own compositions in a concert in Vichy. The critic praises his musical abilities, but does not think much of the composition:

“But about Mr. Miramon, who excels in rendering the most serious difficulties on his instrument, and whose flute leaves and gives way only to the purest sound, without any mixture of breath, I wondered why this artist would prefer to tackle a piece that is only pure marquetry. He calls it fantasy-caprice; my God! I can see that this composition has more to do with warbling than with art or idea; I will pass condemnation on the absence of singing, although this is really the touchstone as well as the pitfall of any good performer. But why this hustle and bustle, these intersecting atoms in music that go on without ever joining? This, it is said, is the merit and the seat of the winning difficulty: difficulty, I agree; but I do not know that music has anything in common with the tour de force of Léonard or Blondin. It charms, that is its role; poetry and music are sisters, and when I see the latter stretching all its muscles to deafen and tire the eardrum, I feel about as much pleasure as when I hear the endless poetic tirade that begins like this: Sarrazin, mon voisin etc. etc. (July 7, 1861 La Gazette)

In December of the same year he performed together with Demersseman.

Charles-Oscar (Carlos) Allard was born in Tournai/ Belgium on July 6, 1823. He must also have been an exceptionally good student, for he too received a first prize at his first concours in 1839 at the age of 16. After his studies, Charles went out into the world. He first moves to Madrid. There are contradictory sources about his time in Spain. On the one hand, it is claimed that he was a professor in Barcelona, others write that he joined the entourage of the politician and diplomat (Juan Gonzáles) de la Pezuela in Madrid and acted as the highest-ranking musician of the Infantry Regiment No. 2 of the Iberian Peninsula. In this position he leaves Europe in the spring of 1848 and embarks on a long journey to the Caribbean. In Puerto Rico he offers his services as a flute teacher in the small town of Ponce. From now on he is called Carlos. For the next few years it is quiet around him. Two of his sons are born in 1851 and 1852. Both will later study trombone in Paris. His daughter Maria Los Angeles is born in 1857. In the same year, Carlos appears in the illustrious company of the American pianist Jean Moreau Gottschalk, who at the time is on a concert tour of America with the fourteen-year-old Adelina Patti and her family. Adelina Patti was about to return to Europe at the beginning of 1858, and plays a farewell concert in Puerto Rico together with Gottschalk and Allard, for which Gottschalk composed a Chant des oiseaux for this trio instrumentation. Unfortunately, the score of this work is lost. After the Patti family left the country, Gottschalk and Allard toured South America together for over a year, where they performed together in many concerts despite many impassable events. I have not found much information about the concert programmes. Apart from a grand solo by Tulou (probably the one of his Concours), he certainly played his own compositions, perhaps also works by Gottschalk.

In 1859, Allard returned to Ponce and resumed his activity as a music teacher. In the 1860s, he finally returned to France with his family, where he became director of municipal music (chef de la musique municipale) in Saint-Germain-en-Lay, west of Paris, in 1866 and founded a harmony orchestra. With this harmony orchestra he performed regularly during the concert season in the music pavilion on the Île du Lac, the so-called Kiosque. The concerts often end with fireworks, and free childcare is also provided in the form of a Punch and Judy show not far from the Kiosque. Allard not only conducts but also regularly performs solo pieces on the flute and piccolo. His repertoire includes Variations on Norma, La Traviata, Demersseman’s Fantaisie sur une Mélodie de Chopin, Solo sur des motifs de la Juive, Polka des Forêts (“imitation and very picturesque and successful reproduction of all the noises that arise under the shade of the woods, from the song of the nightingale, the quail and the cuckoo, to the shots of the hunter and the poacher” (14. 7.1866 L’industriel)), and the polka La Grive and Perle de Venise for one and two piccoli respectively. He received various awards with his orchestra.

A typical concert looked like this:

1. Allegro militaire … Steenebrugen.

2. Fantaisie sur la Fille du Régiment, Soli par MM. Bedejus et Allard fils. … Donizetti.

3. Fantaisie sur Faust, Soli par MM. Bedejus, Poisot et Rebouche … Gounod.

4. L’oiseau de Paradis, polka Exécuté sur le nouvel instrument l’Ocarina, par l’Auteur. … Carlos Allard.

5. Italiana, grande fantaisie (redemandée), Soli par MM. Clauss, Bédéjus, Poisot, Allard fils et Rebuché … Baudonck.

6. Polka de Concert pour deux pistons, Exécuté par les jeunes Bédéjus et Lucas. … Renard.

Allard was dependent on donations for the realisation of the concerts. He regularly published costs and donations in the local newspaper L’Industriel de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. His name appears almost weekly in this newspaper during the concert season. Concert programmes are announced and concerts reviewed. Unfortunately, the newspaper writer is not particularly detailed in his descriptions. His reviews often do not go far beyond the usual praise. The following two reviews are an exception to this:

„To speak of a flute solo played by Mr. Carlos Allard is to say that he must have carried off the audience; this is what happened to our eminent artist performing on his instrument, a solo by Tulou, his master.“ (L’industriel 7.12.1872)

“Mr. Carlos Allard brings his flute to his lips and suddenly there is a deep silence in the crowd, the listeners suspend their breath for fear of losing a single one of those sweet notes, those pearls that are flowing in a hurry, fleeting, from his instrument, which was inert and silent a minute ago and which now seems to be animated by a divine breath. The effect is prodigious, the applause resounds with frenzy, the enthusiasm is at its height, the public is transported, and our musicians contemplate with joy and pride this conductor who gives them such sweet and honourable satisfaction.” (June 19, 1875 L’Industriel)

Judging by the descriptions, it is quite possible that Allard played the flute.

Allard did not only perform in Saint-Germain, but could also be heard from time to time in Paris, as on 16.4.1875 in the Salle Pleyel, where he played his Norma Fantasy.

In Saint-Germain Allard taught solfège and various wind instruments three evenings a week, rehearsals with the harmony orchestra took place on Tuesdays and Fridays. As a teacher, he probably demanded a lot from his pupils, as can be read in the 1895 obituary:

“If he was severe and even a little rough in his lessons. He was an artist to the core, and did not understand that music was treated with a casualness that could harm the progress of the society he was directing; but, also, how attached he was to those who responded to his care. He was no longer simply a teacher, but he made himself the father, the friend of his pupil, and if all those who owe him today what they know about music had followed his convoy, the crowd would have been much larger still. But, alas! So many defections! And how many proved that gratitude was too heavy a burden for some shoulders.” (30 November 1895, L’Industriel de Saint-Germain-en-Laye).

In 1882, he had to leave his post as music director because he got into a dispute with the mayor. The latter took offence at the fact that Allard was Belgian. A foreigner conducting the local orchestra with success could not be tolerated! It must not have been easy for Allard, who had founded the harmony orchestra himself 16 years earlier. But it was all to no avail. Allard took his best musicians with him and founded a new orchestra, the Harmonie du Commerce.

In 1891, Allard was appointed Chef de la Société Philharmonique de Saint-Germain and elected director and president of the association. He not only conducted it but also played the flute in the orchestra. He would hold these posts for four years until he died in 1895 at the age of 72 after a short illness. Many friends, pupils and colleagues attend his funeral, among them Paul Taffanel.

Jean-Théodore Pilliard was born in Troyes in 1819. He was 20 years old when he won the second price. He became Chef de musique du 3e régiment d’infanterie de marine.

The five-keyed flute played in this recording was made by the Godfroy aîné workshop. It has the serial number 4004 and was made around 1836. The flute could be called typical French as it owns Eigenschaften that are found in many French flutes of that period: a soft low and shining high octave which plays easily until C4, it is very easy to play fast staccato passages throughout the range. It has a D-foot, and keys for Bb, G#, F (no long F), D# and for the C-trill. Fork fingerings work very well, therefore keys have to be applied almost exclusively for Bb, G#, F of the low octave and the B-C-trill (the F-key should of course be used for the F#s key-fingerings). The Godfroy workshop produced hundreds of instruments per year, however, their flutes are very individual and need an individual approach. Some fingerings work better on the one than on the other, sometimes registers are either fuller or lighter, some are better in tune than the others. Of course, one has to keep in mind that every surviving flute has an individual biography. Some have been played more or held in better conditions than the others, nevertheless all have been made by hand, thus an individuality of each instrument is a logical conclusion.

The piano is a 1854 Pleyel.

In 1838, the competition of the wind instruments receives little attention in the Parisian newspapers. In contrast to the detailed reports on the competitions for singers, pianists and string instruments, for wind instruments only the names of the laureates are mentioned: Alexis Donjon and Louis-Antoine Brunot share the first prize, Jean-Alphonse Mathieu receives a second prize.

Alexis Donjon, born on April 15, 1822 in Lyon, was 16 years old when he won the first price in the 1838 concours. He won a second price for solfège in 1836 as well as a second price for flute. I found only little information about his further career. In 1839 and 1840 he played the Grand Solo by Tulou in a few concerts in Paris and Lyon. Around 1840 he must have returned to Lyon. In 1843 he was employed at the Grand Théâtre in Lyon, just as his father François who was also a flute player. Alexis‘ son Jean-Baptiste-Marie, born in 1839 and today known for his flute compositions, played the flute as well. Alexis died in 1855.

Louis-Antoine Brunot, born on the 16th November 1820 in Lyon, was 16 years old when he won the first price at the 1838 concours. A year later he won the first price. According to Pontécoulant (1840) Brunot abandoned the Boehm flute after having studied it. He adopted it, however, in the early 1850s. Brunot played in the Orchestre du Palais-Royal, and from 1850 on he was first flute at the Opéra Comique. He also played in the Concerts populaire de M. Pasdeloup and in the Cirque d’Hiver. Brunot published a few compositions for flute, of which only a handful is known today: two fantasies about airs of Webers’ opera Oberon (op. 6,19), a fantaisie originale op. 7, he also arranged airs from Oberon for flute. There is a manuscript of an Adagio in the National Library of France (bnf).

In the 1850s he was at the height of his career. In addition to his orchestral work, he often appeared as a soloist. He played, for example, a duo by Léon Magnier with Louis Dorus, flute quartets by Léon Kreutzer with Simon, Élie, Petition (they all most probably played the Boehm flute), trios by Haydn and duets with singers. In Dorus, Brunot found an equal flute partner, as the author of the Menestrel reports on March 6, 1854: “Never had purity of embouchure, taste, expression, agility, overall precision, smoothness in sound emission, reached this degree of perfection: a thunder of applause broke out at the end of this duet, and the two artists were recalled with enthusiasm.”

The performances of his fantaisie on Oberon, which he repeatedly played in concerts, received many positive concert reviews. L’Écho Rochelais wrote on September 6, 1856: “(The) phenomenon of perfection was achieved by M. Brunot on the flute. To appear alone after [oboe player] Triébert and [bassoon player] Jancourt, to struggle with the deep impressions they had produced, to divert to oneself the current of enthusiasm they had aroused, this was certainly a bold undertaking full of perils. Well! M. Brunot was able to accomplish it, and he won a success equal to that of his rivals, where any other than him would have broken on a reef. Mr Brunot is also a very pleasant enchanter! Armed with his Boehm flute, which is to the old flute what the piano of today is to the piano of thirty years ago, he seduces you, he moves you by the limpidity, the purity and the expression of his singing, he lulls you nobly into the undulations of a vaporous, ethereal melody; he dazzles you, he astonishes you by a fascinating agility of fingering. And then, what suppleness of articulation! What roundness and accuracy of tone in all registers! What sharpness in the double tongue without which it becomes impossible to execute the rapid lines in detached notes! With Brunot, all the native imperfections of the instrument disappear, all the difficulties are smoothed out, overcome. In a variation which delighted the audience and which – a rare thing, an exceptional joy – was enthusiastically requested again, the eminent flute player played both the song with a cadence and a trill, to which two cadences and two trills in the octave were added. Explain this prodigious feat to anyone who can.”

The newspaper L’Aube reports on February 6, 1859: “We remember the words of a famous man who asked what is more boring than a flute, and replied that there are two flutes. We like to think, for the man’s sake, that he must have suffered a great deal from some shrill, false or cold flute to articulate such a proposition. But if he had heard the masters of the instrument, if he had, as we did last Friday, heard M. Brunot make his flute sing, sigh, execute with it the most brilliant organ points, observe the most delicate nuances in the harmonic phrase, go up and down his chromatic scales with a desperate neatness of execution, oh, then the blasphemy would have remained in his throat. He would have said to M. Brunot with us and with Virgil: “Pan, himself, the God of the flute, if he challenged you in front of the whole of Arcadia, Pan, himself, in front of the whole of Arcadia, would confess defeat. “Tulou, the modern Pan, would not have disowned our artist in his Variations and in the fantasy on Oberon. The latter piece, in particular, seems to us to have been composed and executed with a masterly hand. M. Brunot’s talent has reconciled many people with the flute.”

The newspaper L’Aube reports on February 6, 1859: “We remember the words of a famous man who asked what is more boring than a flute, and replied that there are two flutes. We like to think, for the man’s sake, that he must have suffered a great deal from some shrill, false or cold flute to articulate such a proposition. But if he had heard the masters of the instrument, if he had, as we did last Friday, heard M. Brunot make his flute sing, sigh, execute with it the most brilliant organ points, observe the most delicate nuances in the harmonic phrase, go up and down his chromatic scales with a desperate neatness of execution, oh, then the blasphemy would have remained in his throat. He would have said to M. Brunot with us and with Virgil: “Pan, himself, the God of the flute, if he challenged you in front of the whole of Arcadia, Pan, himself, in front of the whole of Arcadia, would confess defeat. “Tulou, the modern Pan, would not have disowned our artist in his Variations and in the fantasy on Oberon. The latter piece, in particular, seems to us to have been composed and executed with a masterly hand. M. Brunot’s talent has reconciled many people with the flute.”

Two years later Brunot played the fantasy on a festival in La Rochelle, and the Messager des théâtres et des arts reports on September 9: “The welcome given to the flute player Brunot was all the more sympathetic as he is a child of the Wester regions [?]. He played his fantasy on Oberon’s motifs to great effect. Brunot is correct, classical; he has a good style, which was very well noticed in the ensemble pieces, where the flute parts are so important.”

The fantasy, however, did not meet everyone’s taste, as we read in La Presse théâtrale on December 15 of the same year: “M. Brunot will not blame me if I like his fantasy on Oberon’s motifs much less. This composition certainly has much to commend it; but I have the weakness of preferring to all the fantasies of the world, to all the variations of the virtuosos, the very motives that inspired them. I like Weber better than M. Brunot: it is a matter of taste! However, M. Brunot is a skilful flute player, whom the audience rightly applauded warmly and recalled. The Cirque, once again, proved that it was not favourable to all instruments: the low notes of the flute do not reach the ear, and the fine nuances are completely lost in this vast expanse.”

Nevertheless did Brunot convince his audience with his tasteful: “This artist has drawn from his instrument sounds of inexpressible sweetness; for him, melody has real charms, and he leaves to others the supposedly great difficulties that those who devote themselves to this instrument enjoy. The audience and the orchestra greeted the performer with long and sympathetic bravos.” (Messager 6.3.1864)

From the late 1860s on he appeared less an less in the national press. He continued playing in the orchestra of the Opéra Comique until his death in 1885.

Jean-Alphonse Mathieu, born on May 10, 1820 in Avignon, was 18 years old when he won the second price in the 1838 concours. Mathieu did not leave many traces. In 1847 he played a concert in Lyon. The Courrier de Lyon notes: “One of the most pleasant surprises of the evening was the fantaisie-caprice, for flute and piano, composed and performed by M. Mathieu. We already knew this artist, and the audience often applauded him as a distinguished flautist. The fantasia-caprice to which we allude has, moreover, shown him to be a skilful and learned composer. In this work, one of the most important and complete ever written for this instrument, M. Mathieu has used some of the sweetest melodies of Félicien Davis’ Symphony ‘Le Désert’ [a peculiar work and worth it to listen to!]. But the introduction and conclusion belong entirely to our compatriot, who has combined the merit of melodic originality with the talent of the arranger. Moreover, in this composition, where the most brilliant part is reserved for the flute, the piano accompaniment is of almost equal importance. To add that this piece was performed by M. Mathieu and by M. Joseph Luigini, is to say that it was rendered with all the charm and perfection of which it is susceptible.” Unfortunately, I did not find a copy of the fantasia-caprice. In 1853 Mathieu played a concert in Vichy. A critic wrote: “The flute solo, composed and played by M. Mathieu, was full of melody and was listened to in silent ecstasy”. In 1867 his name appears in a concert in Grenoble. Mathieu died in 1890 in Nimes.

Mathieu must have composed several works as the fantasy on the Desert symphony is his op. 6. Emil Prill mentions in his catalogue a Grand Solo op. 2, and the National Library of France lists a Grande Valse du Czar par Sigismond Artschkof, (impromptu de concert) variée pour la flûte and La Fauvette captive, caprice-valse, pour flûte avec acc. de piano, op. 19.

In this video I play a flute by the Berlin workshop Grießling & Schlott. I included it in the project because it is a fine example of how ideas and designs originating in France cross borders. On this flute, we find several indications of the influence of French key design.

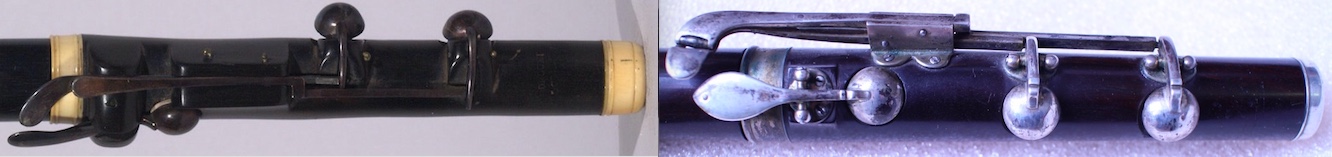

The curved G-sharp key is typical for French flutes, even though it probably originated in Great Britain, as Cahusac was already making such keys in the 18th century.

The pillar mounting of the keys is also typically French. It has been used in France since the beginning of the 19th century, while most German flute makers stuck to the wooden blocks.

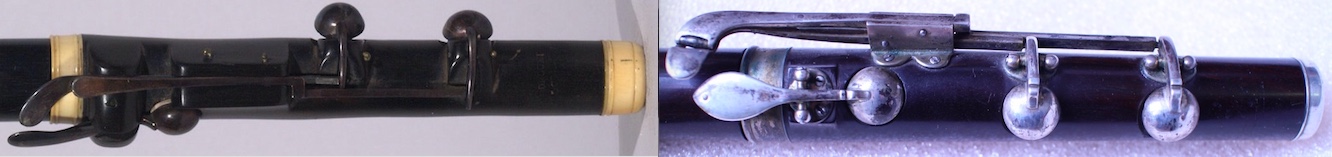

Another feature is the C-foot. A C-foot is needed for the 4th Grand Solo as it contains the only low C sharp of all concours works! This very special key design probably originated from François Laurent, famous for his exclusive crystal glass flutes. The first beginnings of this design can be found as early as around 1815. The Dutch flute player Louis Drouët, who was living in Paris at the time, adopted the idea for his flutes, which he had made in London from 1817 to 1819. A few years later, the design is found on Berlin flutes.

left: C-foot by Drouët (DCM 0347 © Washington Library of Congress, right: Grießling & Schlott)

left: C-foot by Drouët (DCM 0347 © Washington Library of Congress, right: Grießling & Schlott)

In addition to the special arrangement of the shanks and keys, the curved shape of the flaps with their high pads is also striking. These “elastic pads” also made a journey through Europe. It began around 1809 in Paris with the clarinettist Iwan Müller. He developed new pads for his new clarinet in the form of a woolen filled ball or purse made of leather, whose upper edge was folded and tightly sewn. These pads had the advantage of making little noise and closing very well. Drouët seemed to have liked these pads, for they are found on most of his flutes. In 1818, the Clementi workshop in London also adopted these pads for their flutes. Finally, around 1822, they ended up at Grießling & Schlott in Berlin.

Two other features suggest a French model: The D-E trill key has two tone holes. When this key is opened, the C trill key opens as well. This system is often found on flutes from the Godfroy workshop.

Grießling & Schlott D-E trill key, C-trill key and bent G# key

Grießling & Schlott D-E trill key, C-trill key and bent G# key

Finally, in addition to the usual keys, the Grießling & Schlott has a relatively rare F# key. An F# key makes us immediately think of Tulou who is known for this key. However, the key design is different, as it is operated with the little finger of the left hand and is connected to the long F key. This also opens when the F-sharp key is pressed. F-sharp keys already appeared in England in the early 19th century, so they were not invented by Tulou. The arrangement and design of the key by Grießling & Schlott is very similar to the design of some Godfroy flutes. The F# key touch of both flute models has a roller so that it can be used more easily.

Grießling & Schlott F# key with a roller

It is very likely that Grießling & Schlott took one of these flutes as a model.

The high number of keys is very untypical for French instruments, but nevertheless there have been some enthusiasts. Despite all the similarities, the sound of the Grießling & Schlott is quite German, that is, not so fine in the two lower octaves and not radiant in the third octave. On the contrary, it has a warm tone, a full depth and a fine high register, which seemed to correspond more to the German sound ideal of the time.

The piano is a 1854 Pleyel.

“Yesterday it was the turn of the wind instruments, oboe, clarinet, horn, flute and French horn. The wind instruments, in general, do not bring as much success as the string instruments and the piano; so the majority of musicians usually prefer to study the latter, which are undoubtedly more difficult, but which also give, for those who succeed, much more satisfactory results. However, wind instruments are needed for orchestras, where their expressive voices add colour through their great variety. The Conservatoire does a great service to art by propagating the study of these instruments, the shortage of which is keenly felt, not in Paris, where there is a large number of artists who play them admirably, but in the provinces, where sometimes it is impossible, even in fairly large towns, to form a complete orchestra. In general, the jury’s decisions for these various competitions seemed to us to be much fairer than on the two previous days [piano, singing]. The oboe, clarinet and flute classes seemed quite strong.” (Vert-vert August 5, 1837).

Paul-Mérédic Constans, born on 20th April 1821 in Versailles, was 16 years old when he won the first price at the 1837 concours. In 1835 he got first accessit, in 1836 he won the second price. I didn’t find any information about his further career.

Louis-Antoine Brunot, born on the 16th November 1820 in Lyon, was 16 years old when he won the second price at the 1837 concours. A year later he won the first price. According to Pontécoulant (1840) Brunot abandoned the Boehm flute after having studied it. He adopted it, however, in the early 1850s. Brunot played in the Orchestre du Palais-Royal, and from 1850 on he was first flute at the Opéra Comique. He also played in the Concerts populaire de M. Pasdeloup and in the Cirque d’Hiver. Brunot published a few compositions for flute, of which only a handful is known today: two fantasies about airs of Webers’ opera Oberon (op. 6,19), a fantaisie originale op. 7, he also arranged airs from Oberon for flute. There is a manuscript of an Adagio in the National Library of France (bnf).

In the 1850s he was at the height of his career. In addition to his orchestral work, he often appeared as a soloist. He played, for example, a duo by Léon Magnier with Louis Dorus, flute quartets by Léon Kreutzer with Simon, Élie, Petition (they all most probably played the Boehm flute), trios by Haydn and duets with singers. In Dorus, Brunot found an equal flute partner, as the author of the Menestrel reports on March 6, 1854: “Never had purity of embouchure, taste, expression, agility, overall precision, smoothness in sound emission, reached this degree of perfection: a thunder of applause broke out at the end of this duet, and the two artists were recalled with enthusiasm.”

The performances of his fantaisie on Oberon, which he repeatedly played in concerts, received many positive concert reviews. L’Écho Rochelais wrote on September 6, 1856: “(The) phenomenon of perfection was achieved by M. Brunot on the flute. To appear alone after [oboe player] Triébert and [bassoon player] Jancourt, to struggle with the deep impressions they had produced, to divert to oneself the current of enthusiasm they had aroused, this was certainly a bold undertaking full of perils. Well! M. Brunot was able to accomplish it, and he won a success equal to that of his rivals, where any other than him would have broken on a reef. Mr Brunot is also a very pleasant enchanter! Armed with his Boehm flute, which is to the old flute what the piano of today is to the piano of thirty years ago, he seduces you, he moves you by the limpidity, the purity and the expression of his singing, he lulls you nobly into the undulations of a vaporous, ethereal melody; he dazzles you, he astonishes you by a fascinating agility of fingering. And then, what suppleness of articulation! What roundness and accuracy of tone in all registers! What sharpness in the double tongue without which it becomes impossible to execute the rapid lines in detached notes! With Brunot, all the native imperfections of the instrument disappear, all the difficulties are smoothed out, overcome. In a variation which delighted the audience and which – a rare thing, an exceptional joy – was enthusiastically requested again, the eminent flute player played both the song with a cadence and a trill, to which two cadences and two trills in the octave were added. Explain this prodigious feat to anyone who can.”

The newspaper L’Aube reports on February 6, 1859: “We remember the words of a famous man who asked what is more boring than a flute, and replied that there are two flutes. We like to think, for the man’s sake, that he must have suffered a great deal from some shrill, false or cold flute to articulate such a proposition. But if he had heard the masters of the instrument, if he had, as we did last Friday, heard M. Brunot make his flute sing, sigh, execute with it the most brilliant organ points, observe the most delicate nuances in the harmonic phrase, go up and down his chromatic scales with a desperate neatness of execution, oh, then the blasphemy would have remained in his throat. He would have said to M. Brunot with us and with Virgil: “Pan, himself, the God of the flute, if he challenged you in front of the whole of Arcadia, Pan, himself, in front of the whole of Arcadia, would confess defeat. “Tulou, the modern Pan, would not have disowned our artist in his Variations and in the fantasy on Oberon. The latter piece, in particular, seems to us to have been composed and executed with a masterly hand. M. Brunot’s talent has reconciled many people with the flute.”

Brunot in Goldberg: Portraits und Biographien

Two years later Brunot played the fantasy on a festival in La Rochelle, and the Messager des théâtres et des arts reports on September 9: “The welcome given to the flute player Brunot was all the more sympathetic as he is a child of the Wester regions [?]. He played his fantasy on Oberon’s motifs to great effect. Brunot is correct, classical; he has a good style, which was very well noticed in the ensemble pieces, where the flute parts are so important.” The fantasy, however, did not meet everyone’s taste, as we read in La Presse théâtrale on December 15 of the same year: “M. Brunot will not blame me if I like his fantasy on Oberon’s motifs much less. This composition certainly has much to commend it; but I have the weakness of preferring to all the fantasies of the world, to all the variations of the virtuosos, the very motives that inspired them. I like Weber better than M. Brunot: it is a matter of taste! However, M. Brunot is a skilful flute player, whom the audience rightly applauded warmly and recalled. The Cirque, once again, proved that it was not favourable to all instruments: the low notes of the flute do not reach the ear, and the fine nuances are completely lost in this vast expanse.”

Nevertheless did Brunot convince his audience with his tasteful: “This artist has drawn from his instrument sounds of inexpressible sweetness; for him, melody has real charms, and he leaves to others the supposedly great difficulties that those who devote themselves to this instrument enjoy. The audience and the orchestra greeted the performer with long and sympathetic bravos.” (Messager 6.3.1864) From the late 1860s on he appeared less an less in the national press. He continued playing in the orchestra of the Opéra Comique until his death in 1885.

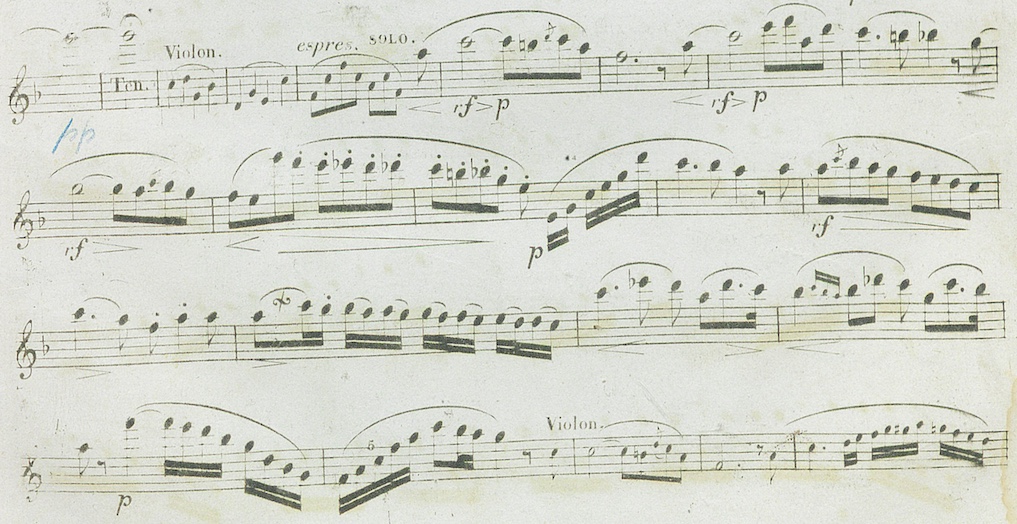

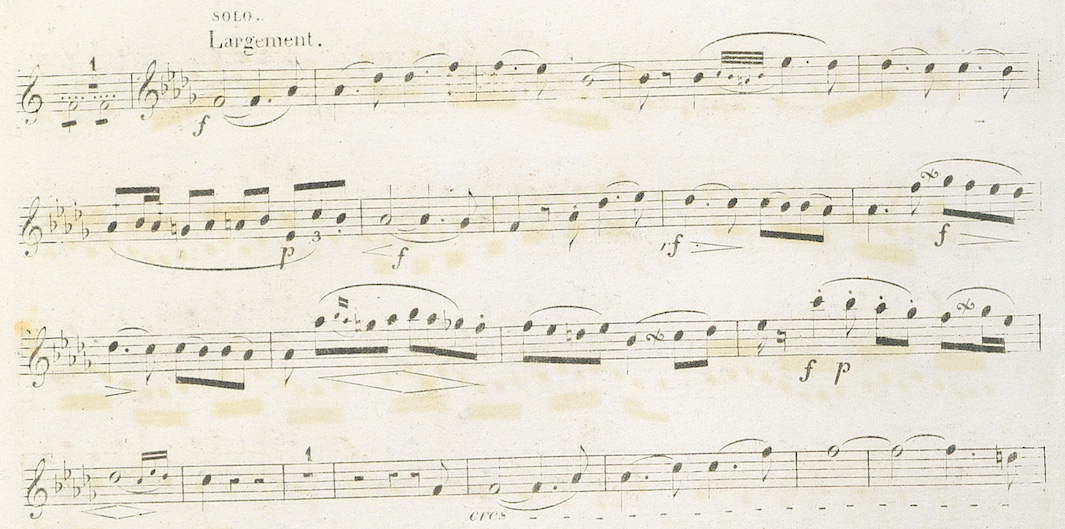

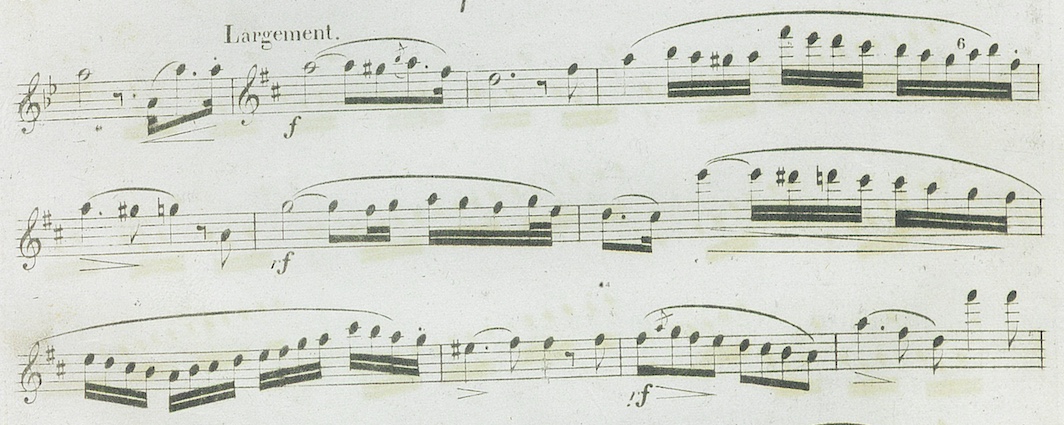

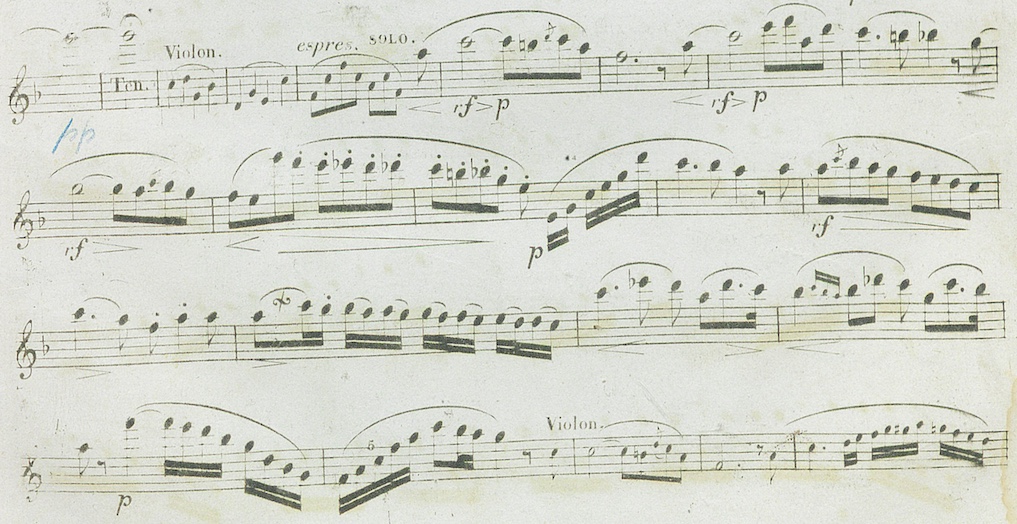

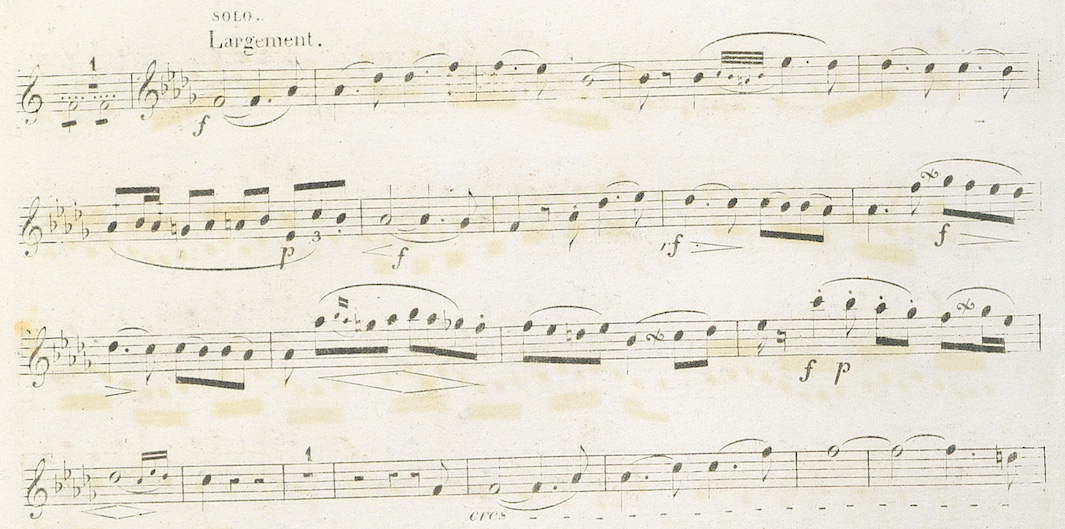

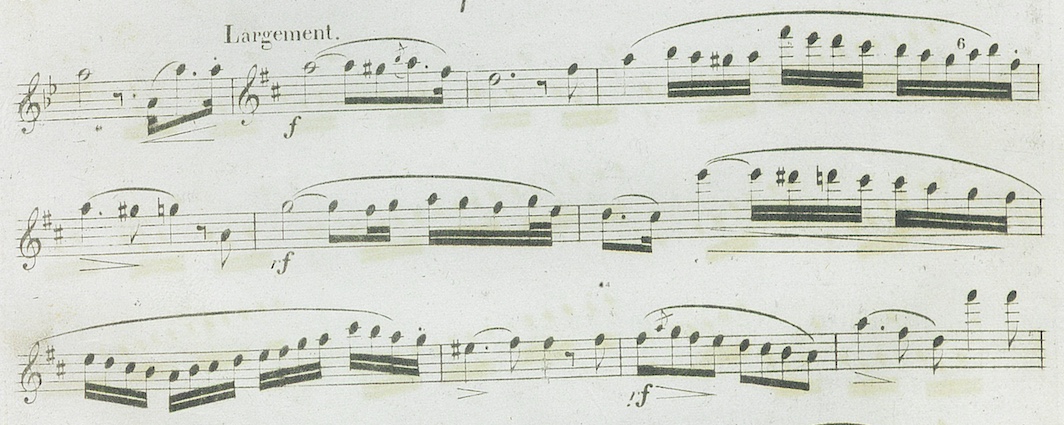

The Troisième Grand Solo is a strange, yet highly interesting and challenging work. None of his Grands Solos is so varied in two respects: Tulou constantly changes from one affect to another, from one tempo to another. Like many Grand Solos, the work begins in Allegro moderato. After the introduction in the piano and the first theme in the flute, a short espressivo passage follows, and after five bars the theme appears again. A virtuoso passage follows, ending with a long A3 under a fermata. Now follows a longer espressivo passage in F major, which can be described as the second theme.

In many 19th century works, the expression espressivo indicates a slower tempo and the use of tempo rubato. In fact, the melody that now follows lends itself very well to both aspects. The difficulty now was to find our way back to the original tempo. We decided to raise the tempo a little with the theme in the piano and to increase the tempo a little more in the following long virtuoso passage in order to achieve greater virtuosity. After this passage and a longer tutti section, there now follows an enchanting middle section in D flat major (!), marked Largement.

When playing it is clear that a distinctly slow tempo is called for here, and here too the melody invites tempo rubato. The end of the Largement is the dynamic climax of the solo, which requires the full commitment of both players. As a contrast, a staccato passage in G minor now begins, followed by the reprise of the second theme.

Instead of espressivo, however, Tulou notates largement here. Do both terms have the same meaning or does Tulou want a different interpretation of the melody here, and if so, which one? Even though the melody is the same, the two themes differ. In the first, it appears after a long fermata and a pause, at which moment the piece has come to a halt. The theme is in F major and begins in piano. In the recapitulation, the theme immediately follows a virtuoso passage, it is in D major, begins in forte and is embellished with many sixteenth notes. Thus, is the largament a warning not to take the tempo too fast? We tried several tempos and finally decided to take it a little slower, though not as slow as in the first second theme or the Largement middle section. At the end of the recapitulation, Tulou also repeats the virtuoso passage of the second theme, before setting off on the final sprint and heralding the end in long staccato passages and the obligatory final runs and trills.

The flute in the video was made in the first third of the 19th century by the Strasbourg workshop Bühner & Keller. It must have been made relatively early in the 19th century, because it possesses some characteristics that clearly point to older, ‘classical’ times. First of all, its sound is very reminiscent of classical flutes: a full, pleasantly warm low register paired with a lighter, but relatively difficult responding high register. The key arrangement, especially the position of the short F key, is reminiscent of that of the first French simple system flutes, as illustrated, for example, in the flute method by Hugot & Wunderlich. The Bb key is positioned relatively high up, so that the thumb is under the key and not to the left or right of it. It makes quite a lot of noise when played. Unlike later flutes, the third octave responds with relative difficulty, so that fast staccato notes above F#3 become a challenge. Some of Tulou’s fingerings work very poorly. Here the older fingerings must be used, such as for the F3. The XXO/XOO/o fingering is much too high, but works relatively well with the slightly too low XXOo/OXX/o or the only slightly too high XXOo/XXoO/o. The B2 fork fingering is also much too high and can hardly be used. Here the B key is indispensable. For a work in D minor like the third Grand Solo, this situation is not ideal. Nevertheless, I decided to play the third Grand Solo on this flute. The decisive factor was its convincing, full depth, which comes into its own very beautifully in the middle section of the Solo.

The piano is a 1843 Pleyel.

The 1847 concours provoked mixed views on the present and the future of the young generation of wind instrument players. The author in Le Constitutionnel (10.8.1847) reported with full of hope: “Speaking of wind instruments and the sublime children who devote their lives to this arduous work! To blow for ten years into a trombone or a clarinet, in order to manage, after much toil, after much work, to earn 800 francs in an orchestra or to keep one’s guard up, is this not proof of self-sacrifice and devotion in a century that is generally accused of ambition and selfishness! The competitions have been very brilliant, and Mr Sax can rejoice in advance. His workshops will not be left idle. Here are the names of the winners: Flute. First prize, Mr. Lascoretz; second prize, Mr. Penas; accessit; Mr Heimbach (sic). (…)”

The author of Le Siècle (8.8.1847) had a slightly different, if not opposite opinion: “The wind instrument classes have not been happy this year, few students have presented themselves, and, with a few exceptions, they have shown themselves to be of a mediocrity that can make us fear for the future of our orchestras.”

In fact both statements could be applied for the candidates of the flute class.

François-Émile Lascoretz was born on 14 October 1825 (or 1826) in Troyes. He came from a family of (military) musicians. His father Jean-Baptiste-François-Antoine l’aîné (1786-1854) played the clarinet and composed. He was the tenant of the Café de la Comédie and ran a music school. In 1835 he went to Paris (this could explain his son’s connection with the Conservatoire) and later returned to Troyes, where he taught music and traded in musical instruments. His younger brother Adrien-Antoine-Jean-Baptiste le jeune (1787-1857) was a clarinetist and military musician, like their father.

François-Emile probably received his first musical training from his father, and he might have received flute lessons from the flute player Arnaud, who took an active part in concert life in Troyes. When Lascoretz was 16 or 17, he entered Tulou’s class. Tulou was very positive about his new student. He reported: „fairly good musician, easy embouchure, fairly good tone, lightness in the fingers, I hope he will become a very good student” (1842). A year later, already, Lascoretz took part at the concours. He got an accessit. He might have felt some pressure to finish his studies soon, because they were financed by the city of Troyes, as we learn from an 1845 concert review: “M. Lascoretz fils, laureate of the Conservatoire, played us on the flute variations on a few motifs of the Diamants de la couronne. There is a future in this young man, who has so far shown himself worthy of the sacrifices the city has made to complete his musical education. However he is a little wary of his petulance of young age, he will be able to give more strength and fullness to tone which already does not lack sweetness and harmony.” (L’Aube 3 April 1845). Nevertheless, it will last another two years before he takes part in the concours again. In the middle of his studies, he somehow lost motivation, as Tulou reported: „quite good embouchure and a lot of ease, he would need solfège lessons (1843); has the means to do well, but his shortcomings in class and his laziness prevented the progress he should have made (1844)”. Shortly after he regained his composure and, after winning a second prize in 1846, completed his studies in 1847. Tulou was quite content: “, is fine; but no apartitude in the class (1845); has made significant progress; good embouchure, very easy, fairly good musician; but little apartitude in the measure (1846); good embouchure – bright fingers, good musician; but a lightness that unites with the good quality of his execution (1847)“ The city Troyes celebrated this success as we read in an article of the Troyes newspaper L’Aube on August 4: “The young Lascoretz, who had obtained the second prize for flute at the Conservatoire two years ago [here the author is mistaken], has just completed with dignity a work so well begun, by meriting the first prize, which has just been awarded to him in the solemn session of the August 3. While congratulating the laureate on this fine triumph, we applaud the fact that the sacrifices made by the city, in favor of this young man, have produced a favorable result. It is rare to achieve such honorable and decisive success. We are told that young Lascoretz is to settle in Troyes. We welcome this resolution with pleasure. The crowned Artist will be a useful auxiliary for the Philharmonic Society; and it is likely that with such a background he will not lack pupils.”

Probably during his studies Lascoretz played in the orchestra of the Théâtre de l’Ambigu-Comique. As his father, his uncle and Tulou he was member of the Association des Artistes musiciens. Back in Troyes he played an active role in the city’s cultural life. He played flute in the Orchestre de la Société philharmonique and a few years he became their conductor. Lascoretz also became director of the Orphéon, a musical institution dedicated to singing and music education, and founded a fanfare, which was expanded to harmony music in 1859. He also composed several pieces, including Trois trios faciles et brillants for flute, horn and bassoon, a polka for piano and orchestra (1853) and a chanson politique et patriotique.

In the Société philharmonique he played and conducted the orchestra at the same time as the author of a review from May 15 1859 reported:

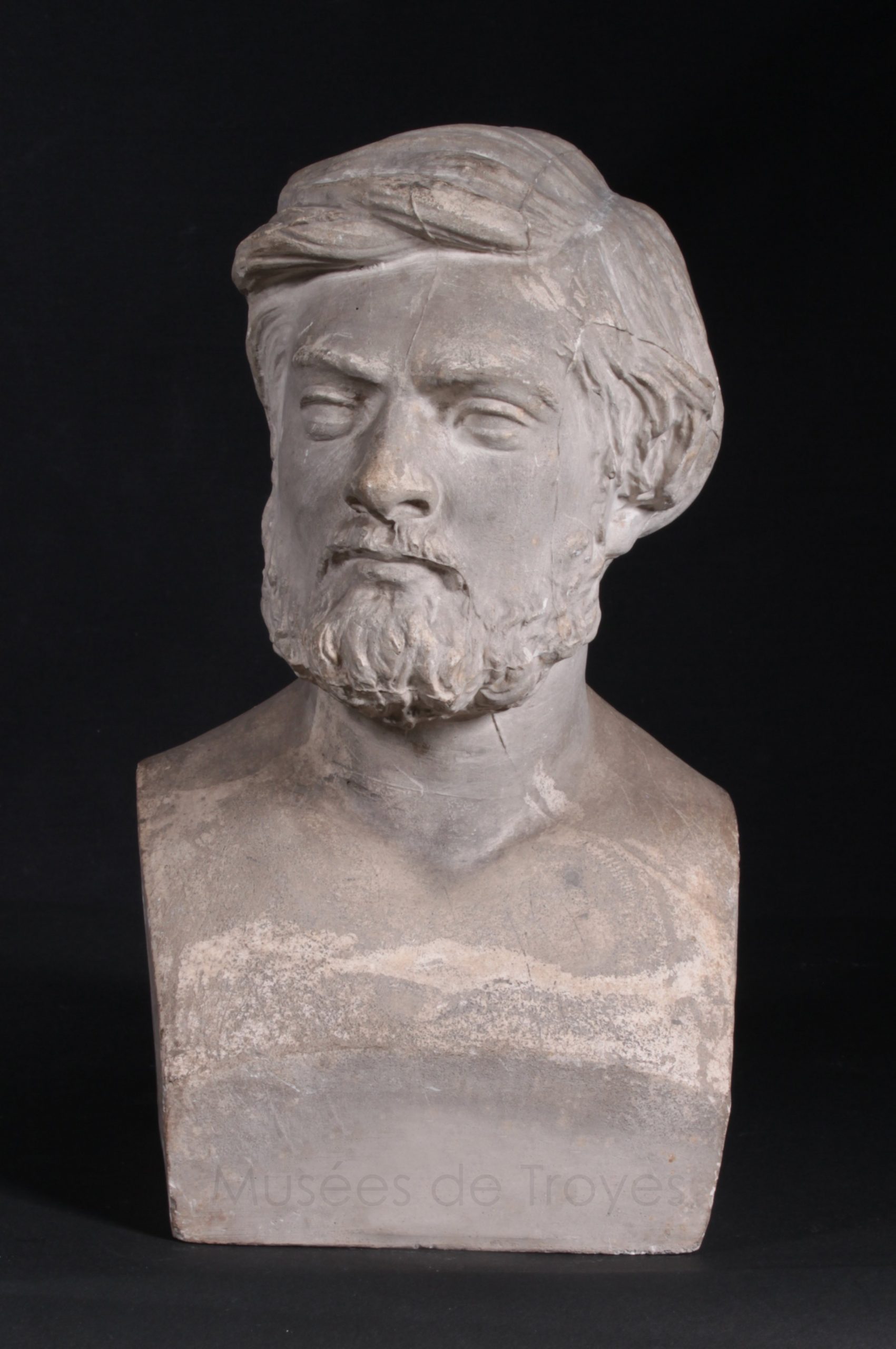

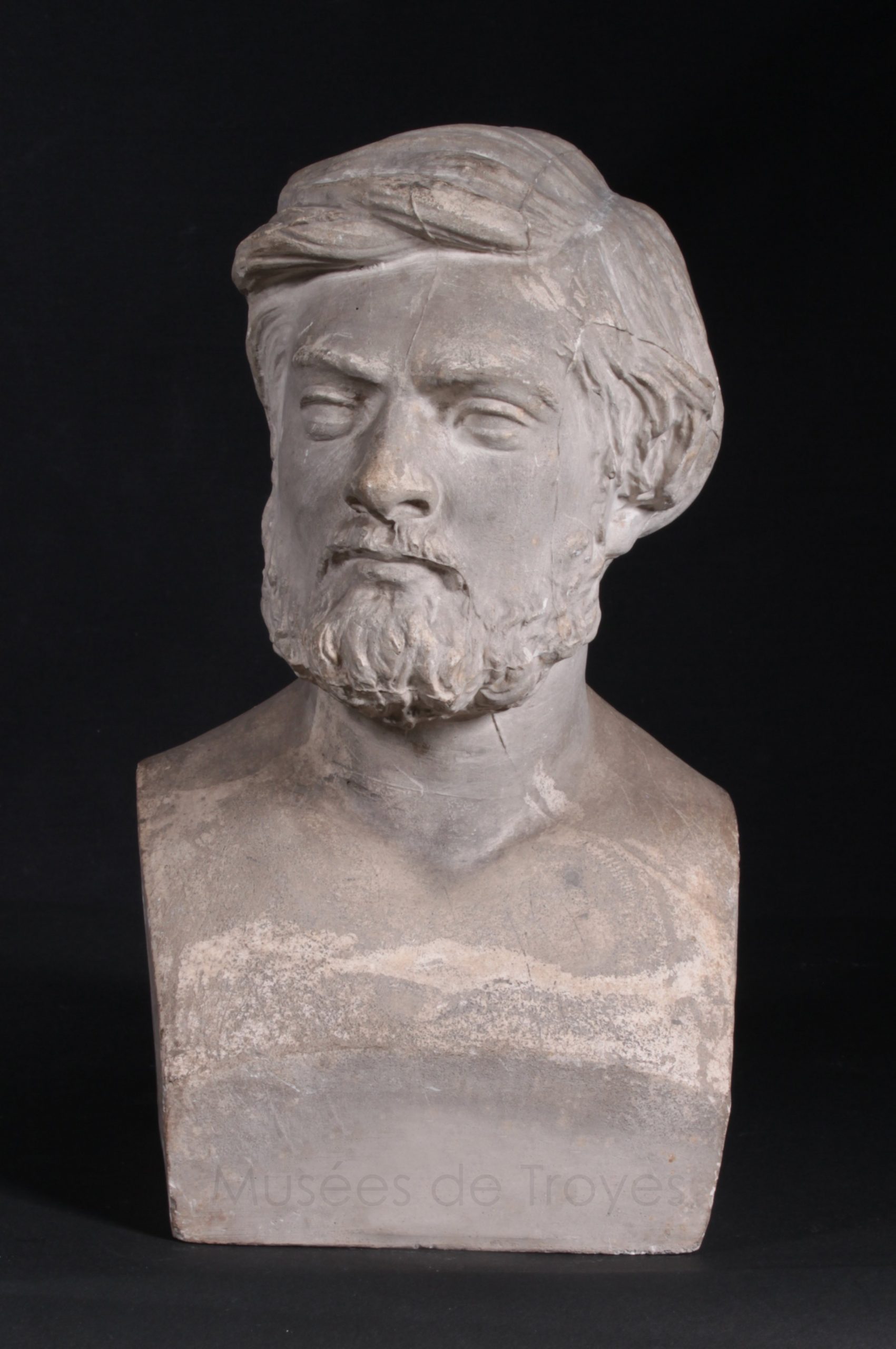

“One can see that he is in control, that he is sure of himself, that he no longer has to reckon with those material difficulties that often cause hesitation and deprive the performance of the brio that takes you away, the casualness that charms. (…) Emile Lascoretz, the Proteus of music by his talent, who can be a first-rate flute player, violinist, cellist and anything else you like, if necessary, did even more in Guillaume Tell; he conducted the orchestra and played the part of first flute at the same time: his instrument was a baton, his baton an instrument, and all of this to everyone’s great satisfaction, thus contributing doubly to the unquestionable success of the masterful overture. Rossini would have been pleased to see his favourite work so perfectly performed.” Unfortunately, François-Emile did not live to be old. He died on 8 September 1860. The Musée d’art et archéologie in Troyes houses a bust of Emile. It was made in 1851 by his friend Louis-Auguste Delécole (1828-1868).

Troyes, musée des Beaux-Arts, photo J.-M. Protte

Not much was written about his playing. There is, however, a short note about the choice of music Lascoretz made for a concert in 1855 that tells us rather more about the author’s taste than about the execution: “Mr. Lascoretz, a distinguished laureate of the Conservatoire, who accidentally arrived in Bar(-sur-Seine) during the concert, and who only gave us an improvisation that was a little too fantastic, made us regret not hearing him in a well-chosen and well-prepared piece. Let’s hope that he will make it up to us at the next concert. In our opinion, the difficulties appeal to few people. As for the mass of listeners, it does not matter to them that an artist has overcome the greatest difficulties, for example, by playing the violin on a single string; by touching the piano with the left hand instead of using both hands, or by playing the flute through the nose like certain Polynesian islanders; what they want are sweet and melodious sounds, music that pleases them like that of Donizetti or Auber.” (Le Petit Courrier de Bar-sur Seine 11 May 1855)

Jean-Baptiste Penas, born on 22 February 1828 in Metz, entered the class on 4 October 1844 at the age of 16. He was 18 years old when he got the first Accessit at the 1846 concours. He played two more concours in 1847 and 1848 where he won the second and first price respectively. Penas was a good student and got good reports since the beginning: “has only been in my class since the beginning of the holidays. I think he will be a good pupil (1844), in (?) at the Conservatoire – good subject, working hard; but not advancing very rapidly; works hard and makes good progress (1845), good worker, has made progress; good pupil (1846), works with zeal – good musician – has made good progress (1847), good musician, easy execution, good orchestral flute. (1848)”

In 1846-47 Penas was flute player in the Théâtre français, and in 1847 he played in the Société philharmonique. Shortly after he must have inscribed in the Gymnase Musical Militaire, another Conservatory in Paris, where he studied solfège and harmony. In 1851 we read in the Revue and Gazette musicale: „Distribution of prizes: (…) Among the crowned students, several took double crowns. One of them, Jean-Baptiste Pénas, of the 7th line regiment, winner of the solfège and harmony, was also made head of music (chef de musique) by the section of the Institute (…) Before the distribution of the prizes, a pas rédoublé, composed by the student Penas, was performed by the cavalry music [= brass band], placed in the open air, next to the room where the session was held (…) [In the following concert] the students Penas and Piau played an oboe duet very well.” (Revue et Gazette de Paris 19.10.1851). Penas stayed in the military and continued leading the 7th line regiment at least until 1859.

Frédéric Heinbach was born on 31 August 1828 in Paris. He won a second price in 1848 and a first price in 1852 at the age of 23 years. Heinbach’s career at the Conservatoire was rather uneven. From the beginning, Tulou did not place much hope in his artistic abilities, and his first judgement is not particularly positive: „only since short time in my class, but I think he does not have the skills to become a distinguished pupil; no ease (1843)” And indeed, he makes only slow progress, as the reports of the following years prove: „bad musical organization; does not have the ease on the flute; no ease for playing the flute (1844), no disposition for the flute, and his progress is not noticeable (1845). In 1847, he finally seems to make progress. Tulou writes: “quite good musician – made sensible progress (1847)” and lets him take part in the concours. He wins a first accessit, yet he makes little progress: “works a lot, and despite that his progress is barely noticeable; worker, progress slow (1848), works with zeal – made progress; little progress, and yet he works a lot; works a lot without great success (1849)” In 1848, Heinbach wins a second prize, but still he will not succeed in completing his studies with a first prize the following year. His zeal, albeit not very successful, prompted Tulou to ask the directorate for an exception to the regulations in 1850: “following the rules, this pupil cannot take part at the concours anymore as he had the 2d price two years ago and had gained nothing last year, nevertheless this young man recovers from a heavy disease that did not allow him to show all he could do on his instrument – in favour of his gained zeal, his exactitude in the class and the awkward position in which he found himself past year, could not you, Monsieur the Director, allow him to present himself again in the concours?”. Heinbach was granted this exception, and Tulou reported hopefully: “I think he will now make a bit of progress”. In his last report in 1851, however, Tulou seems to have finally capitulated: “arrived at a point now that is difficult for him to pass. It’s a good orchestra flute; works a lot without making significant progress”. Nevertheless, Heinbach finally received a first prize in 1852. It is interesting to note Tulou’s statement that Heinbach (despite all his shortcomings) would make a good orchestral flute player. What qualities did he possess for this?

The newspaper L’Aube reports on February 6, 1859: “We remember the words of a famous man who asked what is more boring than a flute, and replied that there are two flutes. We like to think, for the man’s sake, that he must have suffered a great deal from some shrill, false or cold flute to articulate such a proposition. But if he had heard the masters of the instrument, if he had, as we did last Friday, heard M. Brunot make his flute sing, sigh, execute with it the most brilliant organ points, observe the most delicate nuances in the harmonic phrase, go up and down his chromatic scales with a desperate neatness of execution, oh, then the blasphemy would have remained in his throat. He would have said to M. Brunot with us and with Virgil: “Pan, himself, the God of the flute, if he challenged you in front of the whole of Arcadia, Pan, himself, in front of the whole of Arcadia, would confess defeat. “Tulou, the modern Pan, would not have disowned our artist in his Variations and in the fantasy on Oberon. The latter piece, in particular, seems to us to have been composed and executed with a masterly hand. M. Brunot’s talent has reconciled many people with the flute.”

The newspaper L’Aube reports on February 6, 1859: “We remember the words of a famous man who asked what is more boring than a flute, and replied that there are two flutes. We like to think, for the man’s sake, that he must have suffered a great deal from some shrill, false or cold flute to articulate such a proposition. But if he had heard the masters of the instrument, if he had, as we did last Friday, heard M. Brunot make his flute sing, sigh, execute with it the most brilliant organ points, observe the most delicate nuances in the harmonic phrase, go up and down his chromatic scales with a desperate neatness of execution, oh, then the blasphemy would have remained in his throat. He would have said to M. Brunot with us and with Virgil: “Pan, himself, the God of the flute, if he challenged you in front of the whole of Arcadia, Pan, himself, in front of the whole of Arcadia, would confess defeat. “Tulou, the modern Pan, would not have disowned our artist in his Variations and in the fantasy on Oberon. The latter piece, in particular, seems to us to have been composed and executed with a masterly hand. M. Brunot’s talent has reconciled many people with the flute.” left: C-foot by Drouët (DCM 0347 © Washington Library of Congress, right: Grießling & Schlott)

left: C-foot by Drouët (DCM 0347 © Washington Library of Congress, right: Grießling & Schlott) Grießling & Schlott D-E trill key, C-trill key and bent G# key

Grießling & Schlott D-E trill key, C-trill key and bent G# key